How to get the best secret dishes at a restaurant without being obnoxious

Growing up Chinese American in California, my experience with “secret menus” at restaurants extended mostly to asking for “animal style” at In-N-Out Burger. But Momofuku restauranteur David Chang wants you to “badger” Chinese restaurants for the “real” menu.

Growing up Chinese American in California, my experience with “secret menus” at restaurants extended mostly to asking for “animal style” at In-N-Out Burger. But Momofuku restauranteur David Chang wants you to “badger” Chinese restaurants for the “real” menu.

In the seventh episode of his new food documentary series on Netflix, Ugly Delicious, the Korean American chef explores the complexities of Chinese cuisine throughout its various evolutions in the diaspora.

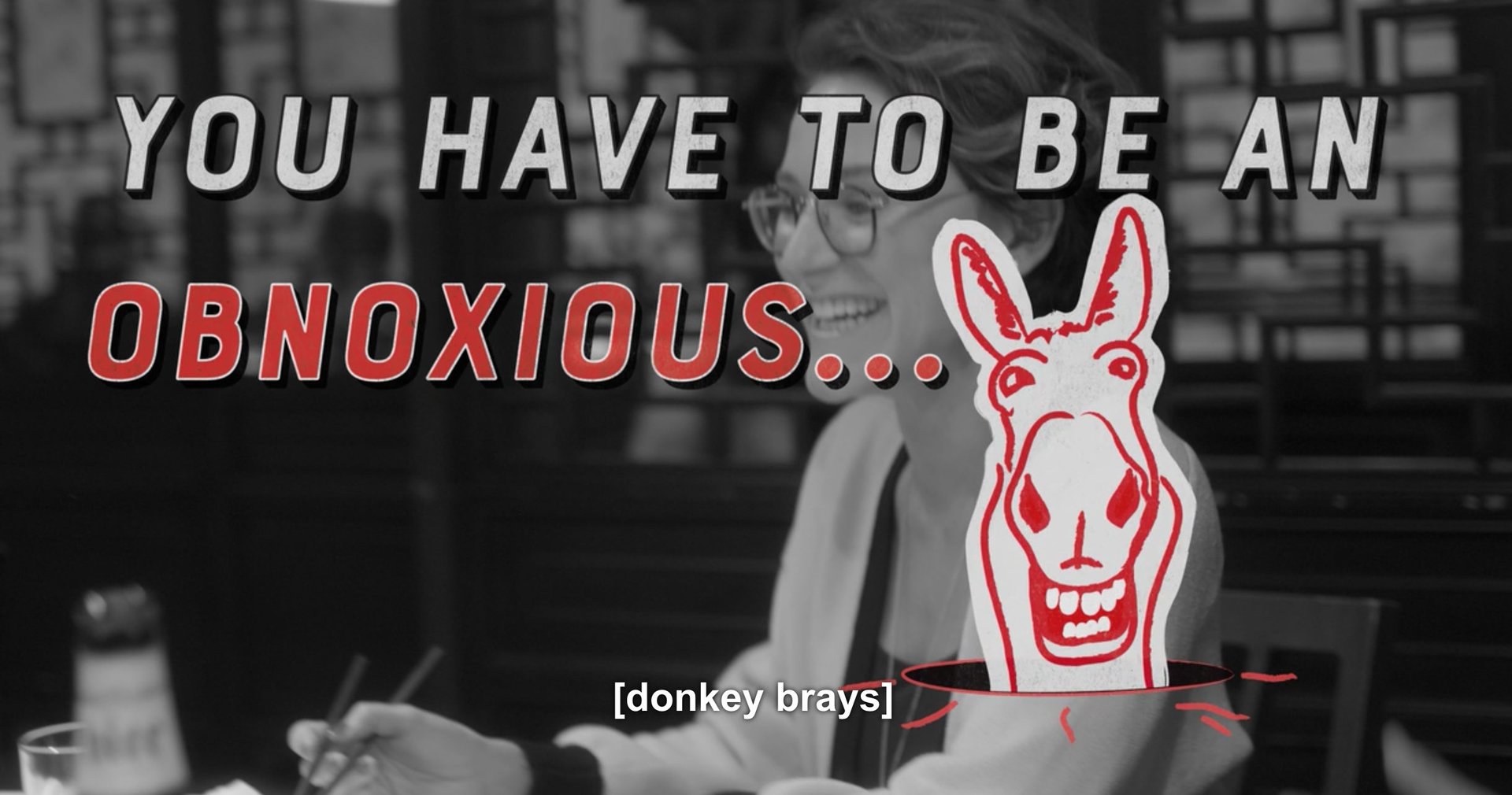

“You just have to badger them to the point where it’s like, ‘I’m just going to give you something so you leave us alone,'” he advises the viewer about scoring DL menus. “There’s no way to do this without coming across as a obnoxious [donkey bray].”

Chang says all this while sitting in a Chinese restaurant, Newport Seafood in San Gabriel, California, where a waiter tells him that there is no secret menu. “Oh, that’s not true, come on,” he says. “Whoever’s peacocking the largest is gonna get the attention.” He knows, he says, that the restaurant has secret ways of preparing lobster.

Many restaurants do have unwritten specialties or so-called “secret” items that can be ordered, if the ingredients are available and the chef is feeling up to it. But the optics of Chang—a wealthy non-Chinese person—sitting with his white friends at a Chinese restaurant and harassing a waiter for the “real” menu, is troubling. He encourages the viewer to be similarly “obnoxious” and “badger” Chinese restaurant waiters for the good stuff. (He never suggests you to be obnoxious at Japanese or French or Italian restaurants.)

My parents and I, who are first-generation Americans from China, do not ask for “secret” menu items at Chinese restaurants. But we’re lucky—the San Francisco Bay Area has a huge Chinese population. The “authentic” dishes are already on the menu, and the most reputable restaurants have no need to hide them from white American palates.

Chang is presumably talking about going to a Chinese restaurant that sits in a mostly white American suburb, where it is one of few establishments of its kind in the area. There, you might find fusion-follies like deep-fried wontons stuffed with cream cheese, sweet-and-sour chicken, and egg foo young. There, you will probably need to ask for chopsticks because the default table setting is forks and knives. At this restaurant, you may have a few actual Chinese customers in the area who come in asking for “authentic” off-the-menu dishes.

Here are some polite ways to ask for an off-the-menu item:

- “Do you have any specialties of the day?”

- “I see the table over there eating something that looks amazing/interesting. Is it on the menu? Is it still available?”

- “We’d like to try something new today. What do you recommend?”

- “Are there any items on the Chinese language menu that isn’t on the English language menu? Do you mind translating these items for us?”

Don’t, as Chang advises, be obnoxious. And don’t assume you’re entitled to “authentic” dishes from Chinese restaurants that have tried their best to adapt to American palates. (Earlier in the show, Chang spits out a piece of deer tendon at a revered restaurant in China, providing a pretty good illustration of why Chinese American restaurants give squeamish guests dishes like orange chicken.)

My rule, and my parents’, is to think of yourself as a guest in the restaurant. When the chef makes them something special that reminds them of their home in China, it’s a special favor. It is not a right—even if you are a world-famous chef.