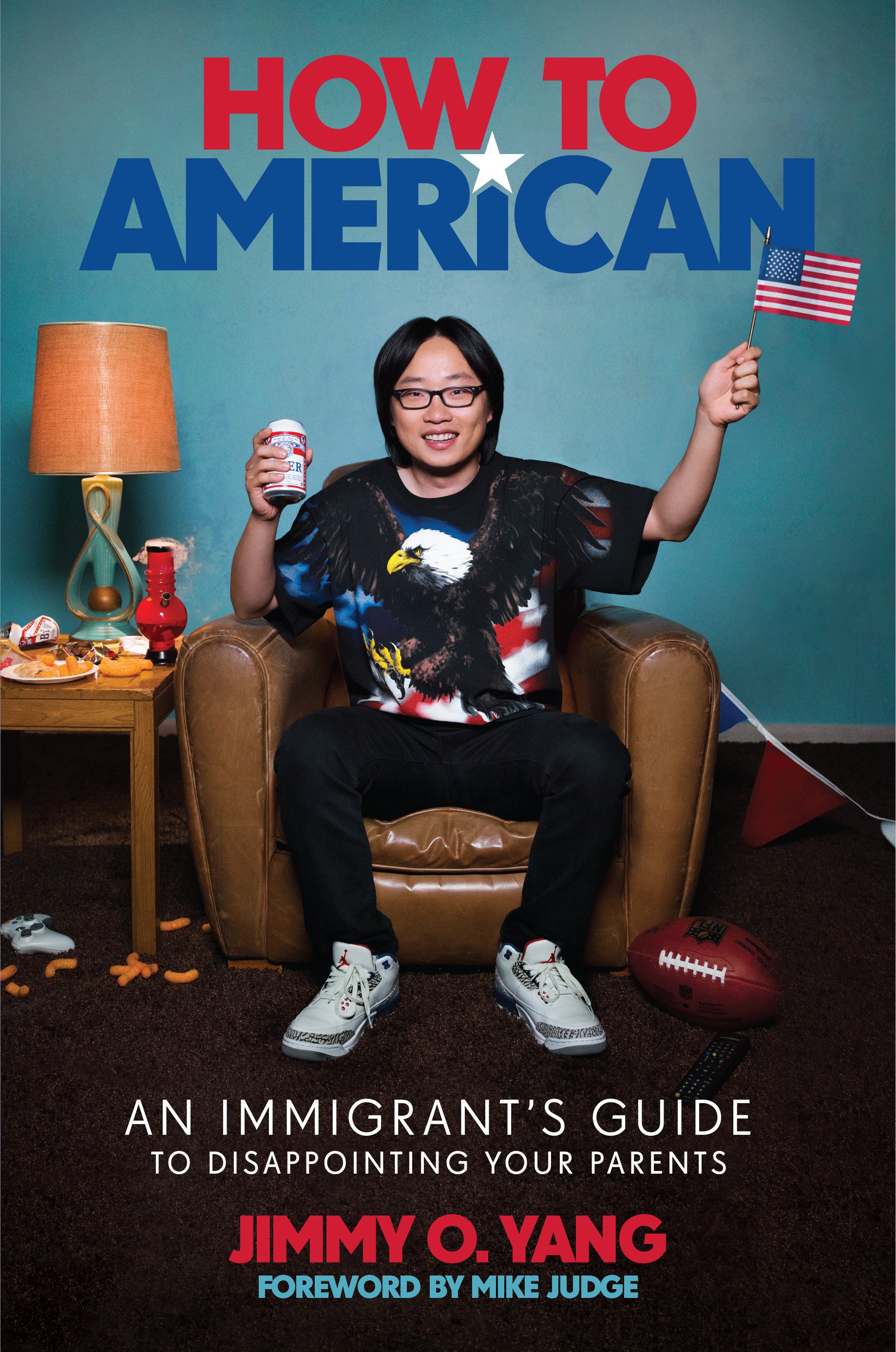

The actor who plays Jian-Yang on “Silicon Valley” wrote a self-help book for immigrants

Immigrants to the US will find much to relate to in the new memoir by the Chinese-American actor and comedian Jimmy O. Yang, How to American: An Immigrant’s Guide to Disappointing Your Parents.

Immigrants to the US will find much to relate to in the new memoir by the Chinese-American actor and comedian Jimmy O. Yang, How to American: An Immigrant’s Guide to Disappointing Your Parents.

“In America, people will always tell me, ‘Money can’t buy happiness. Do what you love,’” writes Yang, best known for playing the Chinese app developer Jian-Yang on the HBO comedy Silicon Valley. “In my Chinese family, my dad always tell me: ‘Pursuing your dreams is for losers. Doing what you love is how you become homeless.’”

Needless to say, Yang didn’t follow this dad’s advice, and the book is not your conventional rags-to-riches, pull-oneself-up-by-one’s-bootstraps immigrant story. It begins almost 20 years ago, when Yang arrived in Los Angeles as a teenager, after his family left behind their middle-class lives in Hong Kong.

As a student at Beverly Hills High School, Yang picked up American culture by watching the cable network BET, through which he fell in love with hip-hop and comedy. After doing an economics degree, Yang turned down a job at a financial firm to pursue comedy, a move that his father considered delusional. He worked odd jobs to support himself—including selling used cars and spinning music as a strip club DJ—as he went through the grind of auditions.

His big break on Silicon Valley led to roles in such films as Patriots Day and Life of the Party. Years after the move to America, he finally became US citizen.

The memoir has plenty of funny anecdotes, such as Yang’s brief stint as a hip-hop music producer whose beats were used on a porn site, or when he accidentally snorted cocaine given to him by a bike rider in the park. But the heart of Yang’s story lies in the dilemma of being caught between the traditions of his Chinese parents and the opportunities and independence offered by America.

Here are some takeaways from How to American:

The “model minority” is a myth

Yang doesn’t describe cramming or doing homework around the clock at the expense of having a social life. Instead, when he was a student at UC San Diego, Yang grew his hair out, skipped classes, and smoked weed while trying to find some direction in his life. “I tried my hardest to be the opposite of a stereotypical Asian student,” he writes.

Younger or second-generation immigrants may relate, as I did: As a Chinese-American myself, I never liked science, math and biology, but instead loved history, art and English. And like Yang, I became a sponge for Western pop culture and professional sports.

Like many of us, Yang bucked against the Asian “model minority” myth, perpetuated by stories like the controversial “Asian whiz kids” cover story of a 1987 Time magazine which posited that Asians are a naturally gifted, smart and hard-working bunch, who overcome obstacles without complaining. The dark side to that myth is it overlooks the struggles of Asians; it adds to the academic and emotional pressure facing Asian teens; it masks ongoing discrimination and disparities in advancement; and most perniciously, it drives a wedge between Asians and other minority groups.

Playing the immigrant doesn’t mean mocking the immigrant

Jian-Yang, an immigrant developer from China who speaks with thick accent on Silicon Valley, has drawn some charges of stereotyping. But Yang says he takes pride in portraying immigrant characters, countering such criticisms by citing his role as the real-life Danny Meng in Patriots Day, about the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing; for that part, he learned to speak with a Sichuan accent.

“I’ve come across people who had a negative opinion about playing Asian characters that have an accent,” he writes. “They believe these accented characters reinforce the stereotype of an Asian being the constant foreigner. I can understand that. But frankly I can’t relate…Just because I don’t speak English with an accent anymore doesn’t mean that I’m better than the people who do… There are real people with real Asian accents in the real world. I used to be one of them. And I’m damn proud of it.”

There’s a racist double-standard at play, even between what various accents connote on screen, Yang has pointed out: “When a Spanish actor does an accent, that’s sexy,” Yang said in a 2016 interview with Time ”When Peter Sellers did a French accent in Pink Panther, that’s funny — he got nominated for a Golden Globe. How come whenever an Asian actor does an accent, he’s stereotyping? The problem is not in the accent itself. It’s the perception of the accent.”

Asian men can be sexy too

Yang also addresses the longstanding unspoken Hollywood rule of not depicting Asian men in relationships with non-Asian women. Asian male characters have often been depicted as martial arts figures, like Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, or sidekicks; emasculated nerds such as Long Duk Dong from Sixteen Candles and Toshiro from Revenge of the Nerds; or offensive caricatures going back to Mickey Rooney’s buffoonish neighbor in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. These perceptions of Asian masculinity — or rather lack thereof — have been pervasive, evoked again recently by the comedian Steve Harvey.

That taboo has only recently been broken with TV shows such as The Walking Dead, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, and Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, and in films including The Edge of Seventeen. Yang himself plays the Asian boyfriend of a white girl in the Melissa McCarthy comedy Life of the Party.

“I was happy to change that,” Yang writes. “This was not just about me; this was making all my Asian brothers look sexy.”

While there has been progress in portraying Asian characters with more range and depth in Hollywood—and a slew of rising stars including John Cho, Mindy Kaling, and Steve Yuen—the industry still doesn’t get it when it comes to casting Asian characters. Charges of “whitewashing” have been leveled at recent movies that cast white actors to play characters originally conceived as Asian, including Annihilation, Ghost in the Shell, and Doctor Strange.

Yang’s log of auditions he went on for commercials and TV shows, published in the memoir, offers a glimpse of how Hollywood still sees Asians: “computer geek,” “Chinese ping pong player,” “awkward techie nerd,” and “plays violin.”

Find your own way to be a good son or daughter

Ultimately the message that emerges from the book is that success is not always measured by a straight A or a lucrative profession. And that’s the advice that Yang gives his readers: “Pursue what you love, not what you should.”

He found a way to be the “good son” while forging his own path. “So instead of forcing my parents mindset,” he writes, “I quietly rebelled. I obeyed my parents’ rules inside our Chinese household while I pursued my dreams in the American world outside. I had to disappoint them to pursue what I loved.”

During a period in his life where he felt directionless and lost, Yang was inspired by a graduation speech delivered by Beavis and Butt-head mastermind Mike Judge (Yang would end up starring in Judge’s current series, Silicon Valley). “It gave me the permission to quit what others thought I should do and find something I was truly passionate about,” he recalls.

While filming the upcoming movie Crazy Rich Asians, Yang recalls, he returned to Hong Kong after a long absence. With its mostly Asian cast, including Constance Wu and Ken Jeong, he found now that there was no need to hide, explain, or push back against his Asian-ness. “Everyone made each other feel proud to be Asian,” Yang writes. “For once in my life, I wanted to flaunt my Asian side instead of hiding it to fit as somebody else….Crazy Rich Asians made me want to get in touch with my roots, instead of running away from them.”

It’s not new advice: Find a path that allows you to be who you are, not what others want you to be. But framing that message within an Asian immigrant narrative, even today, feels like a breakthrough.