Almost anyone can—and should—learn to sing

Do you have a pair of vocal folds that can produce sound? Can you tell the difference between a higher note and a lower note? Good news! You and about 98.5% of the population absolutely can be taught how to sing.

Do you have a pair of vocal folds that can produce sound? Can you tell the difference between a higher note and a lower note? Good news! You and about 98.5% of the population absolutely can be taught how to sing.

And the rest? Well, according to a recent Canadian study, about 1.5% of the population suffer from a condition called “congenital amusia.” They have real difficulty discriminating between different pitches, tone, and sometimes rhythm.

So if you were to play a well-known melody—say, the tune to “Happy Birthday”—and you played a few wrong notes, most people would identify the errors straight away. However, someone with congenital amusia might not notice anything wrong at all. You can see examples of that in this video, from about the 3:20 mark:

Natural talent aside, most of us can be taught to sing

Several years ago I had a request for private vocal lessons from a woman who just wanted to sing one song for her husband’s birthday in six months time.

What I noticed was that she was unable to accurately pitch match. She came to lessons each week and maintained her practice with incredible diligence. What she lacked in natural ability, she made up for in heart and work ethic. Within six months, she was not only matching pitch, but she was singing one and a half octave patterns slowly through her entire range (for example, from low C to A in the next octave up).

More importantly if she sang a note incorrectly, she could discern and correct it herself. She performed the song for her family and it was a happy outcome for all involved.

Her experience shows that hard work pays off, but that’s not the only factor. Work by German researchers found that that it is not just how much you practice that counts, but rather how quickly you identify and correct your error. This is what makes an okay singer into an expert performer. That said, without deliberate practice even the most talented singer will reach a plateau and get stuck.

How singing works

Understanding exactly how singing works is a surprisingly complex field of research. There is a rather significant leap from singing in the shower or being part of a community choir (although both are a great place start) to pursuing singing professionally.

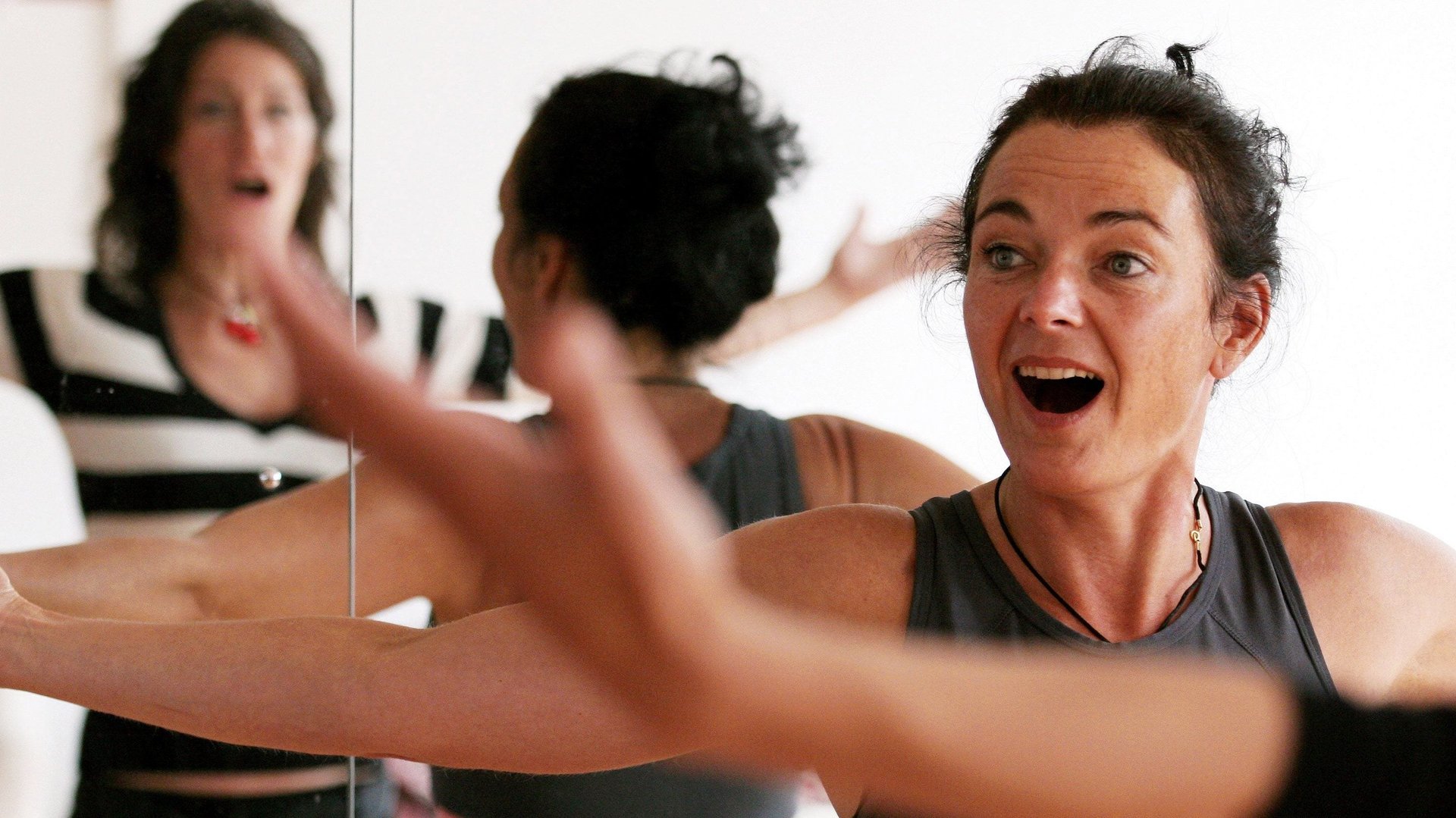

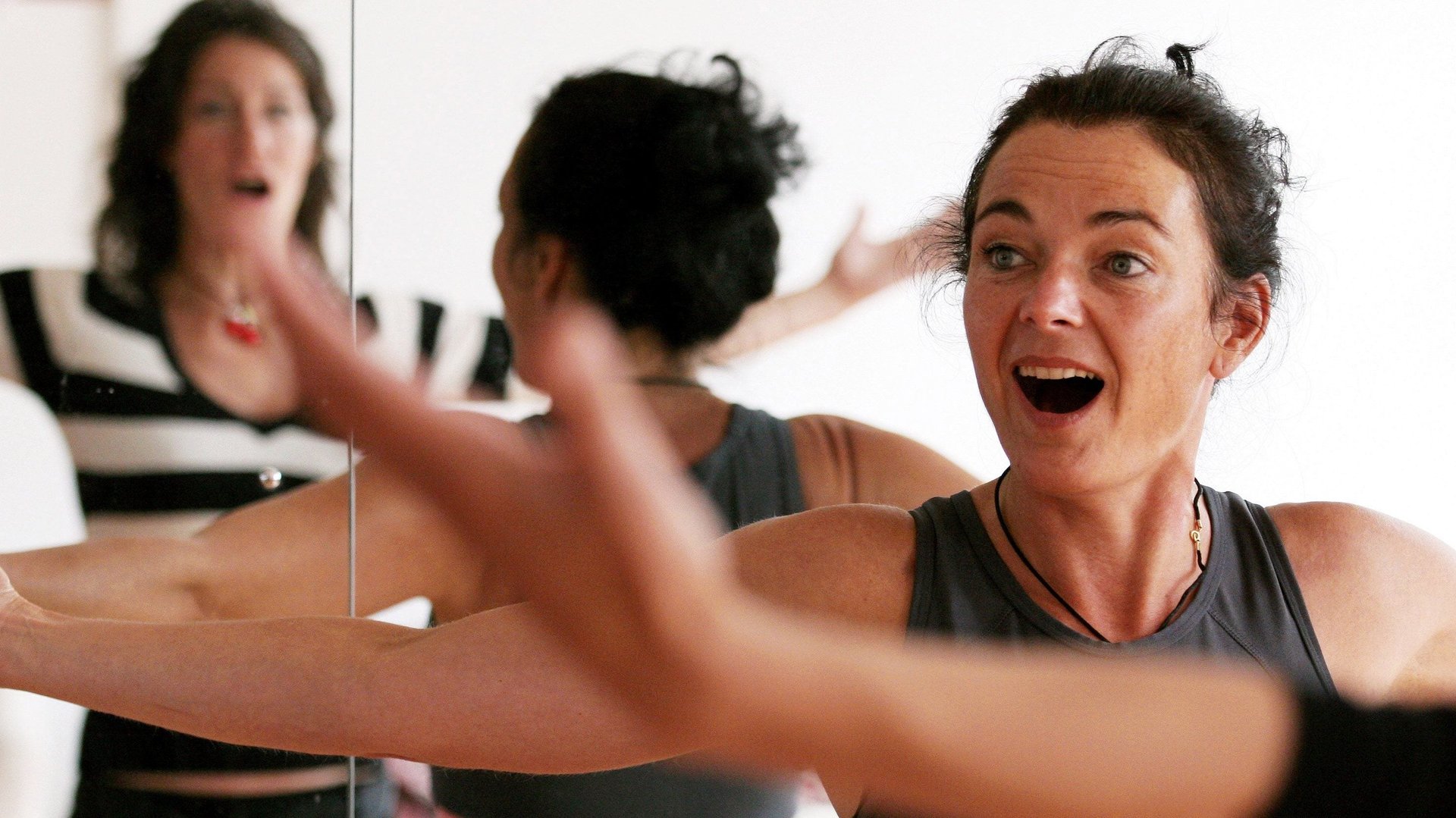

Singing practice and training involves generating a sense of vocal freedom—this is what you’re seeing when you watch someone sing movingly, beautifully but seemingly without effort. For most singers, years of practice go into developing that kind of freedom.

As singing voice teacher Jeannette Lovetri writes:

It takes about 10 years to be a master singer. Ten years of study, investigation, involvement, experience, experiment, exploration, and development, and in some way, that’s when you start really being an artist.

We are all born with the key ingredients of a singing voice. The early gurgling and bubbling sounds we make as babies contain some of the key components of singing—a variety of pitches, dynamics, rhythms and phrases. But some of us may have a genetic advantage that can be enhanced by training.

A University of Melbourne study called Let’s Hear Twins Sing aims to discover what factors influence singing ability and to what extent genes play a role in pitch accuracy.

Physical skill and control

The act of singing looks simple but actually involves highly skilled control and coordination of muscles—and these muscles need to be both flexible and strong. True control comes from training.

A person needs to be able to control the air pressure in their lungs and use their abdominal muscles to push air through the trachea, where it meets the vocal folds, which start to vibrate. In a really good singer, vocal health, posture and alignment, breath management are matched with imagination, self-expression and creativity.

A really good contemporary professional pop singer isn’t just born that way. They also need an inquiring mind, dedication to understanding the physiology of the vocal instrument, the discipline and daily practice of warm-ups and a variety of exercises, a deep understanding of music harmony, ability to notate and transcribe music, some degree of improvization and stagecraft skills.

Film stars learn to sing all the time for a role (usually surrounded by a team of vocal teachers and months of daily practice). The results aren’t always perfect, but that’s not necessarily what is important. Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, for example, has a small, breathy voice but it suits her role and enhances her character.

So if you’ve never sung professionally but want to try singing, I encourage you to give it a go! Chances are that you can be taught to sing—and even if you can’t, there are health benefits to trying.

Singing increases breathing control and lung capacity, it can improve heart health, and release the happy hormone oxytocin, elevate your mood and reduce pain, and may even increase your immunity. Even practicing a new behavior, like singing, can be good for the brain.

So enjoy singing. Find a singing teacher who loves singing and teaching, performs regularly and incorporates their knowledge of anatomy and physiology into their vocal teaching. Once you start, you’ll likely realize that singing can bring benefits for life.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.