Anthony Bourdain didn’t just teach us how to travel. He taught us how to live

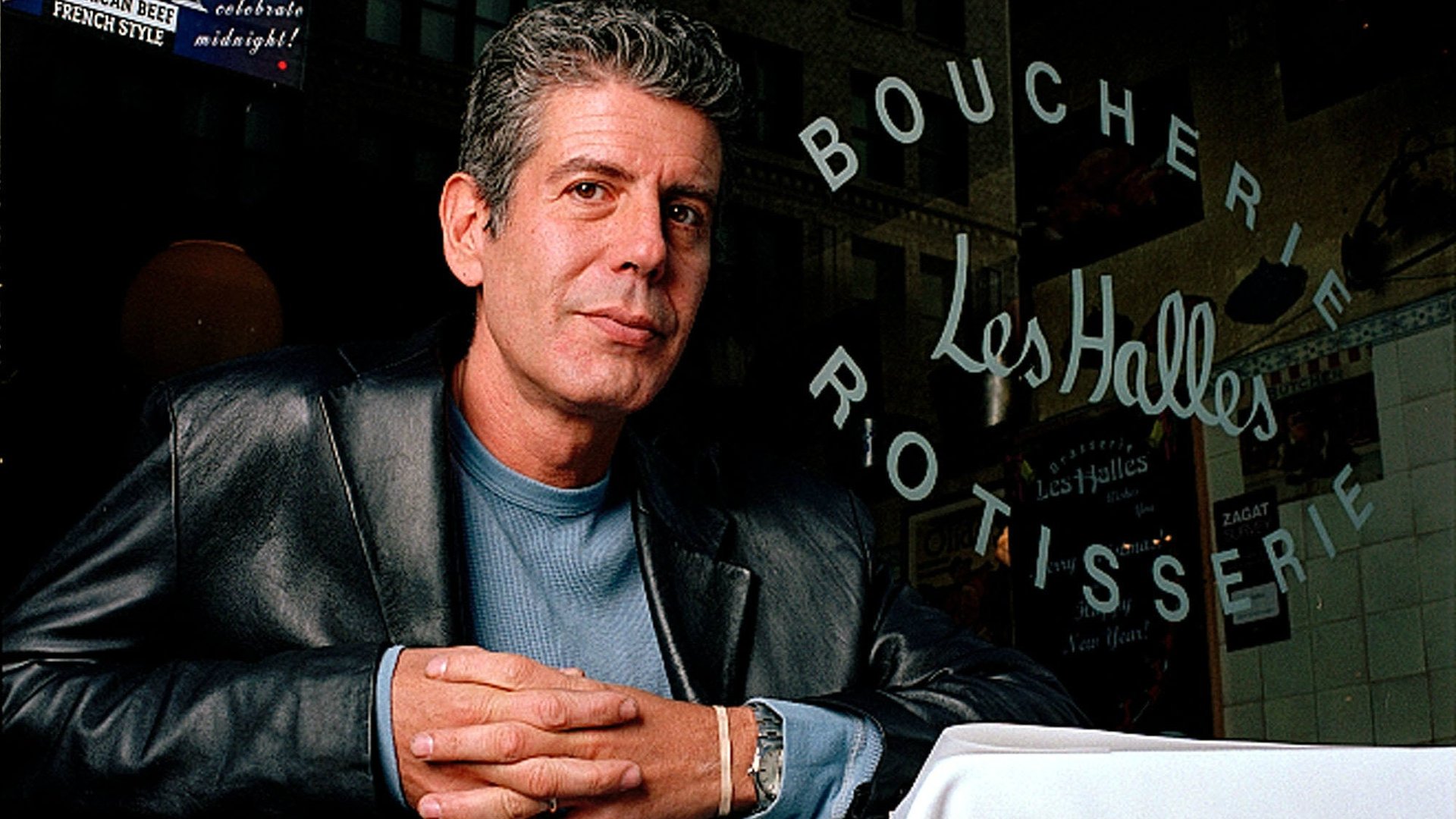

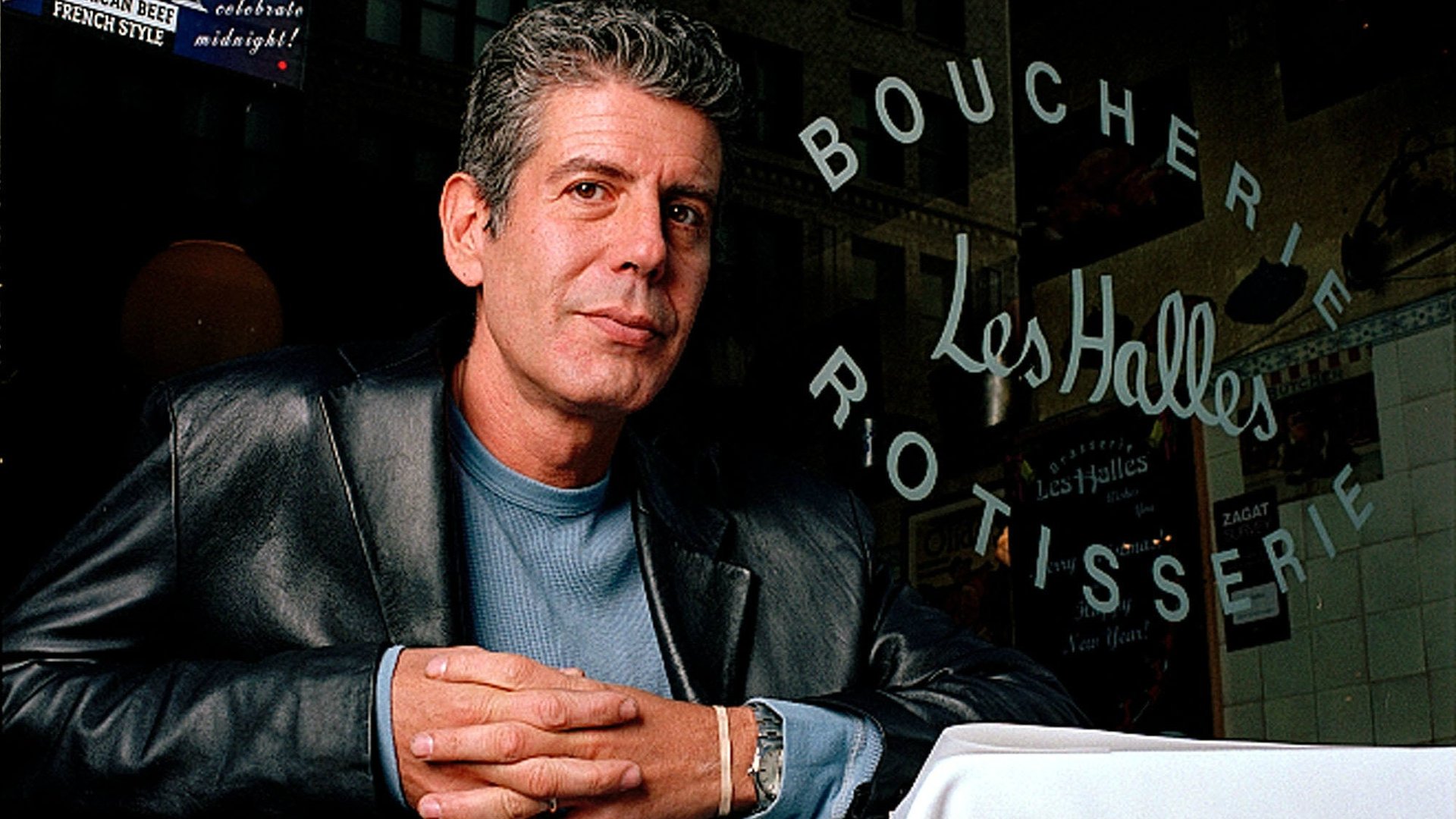

There’s a quote from the late chef, writer, TV personality, and traveler Anthony Bourdain that I send to friends whenever they ask me for recommendations of what to do in Paris:

There’s a quote from the late chef, writer, TV personality, and traveler Anthony Bourdain that I send to friends whenever they ask me for recommendations of what to do in Paris:

Most of us are lucky to see Paris once in a lifetime. Please, make the most of it by doing as little as possible. Walk a little. Get lost a bit. Eat. Catch a breakfast buzz. Have a nap. Try and have sex if you can, just not with a mime. Eat again. Lounge around drinking coffee. Maybe read a book. Drink some wine. Eat. Repeat. See? It’s easy.

In a practical sense, it’s simply great advice. But also, in so few words, it captures everything I love about Paris, travel, and Bourdain himself. Which is to say: It captures everything I love about being alive.

That, of course, is what Bourdain did so well. His travel writing wasn’t just tips on how to scope out good street food or how to seamlessly navigate an airport. It laid out an attitude for living. Whether he was looking chic in Milan or dusty in Mozambique, he possessed a no-bullshit vitality, a humble awareness of his privilege as a white, male American, and an appreciation for the things—cold beer, hot noodles, the fact that seafood always tastes better when you’re barefoot in the sand—that are true no matter where you find yourself on this big, generous earth. He taught us that the best way out of your privileged or narrow-minded comfort zone was to plunge right into the chaos of the unknown—and to consume as many spicy, meaty, and alcoholic things as possible along the way.

Bourdain had an impact on my life in a way that directly led to what I do now, as a writer who focuses on travel. Reading his books and watching his shows slumped on my parents’ couch as a teenager, I desperately wanted whatever that was. That sweaty film that dappled his forehead as he drank a cold beer on a hot day; the look of industrious seriousness with which he approached a steaming hot bowl of noodles; the earnest politeness and gratitude with which he unfailingly treated his hosts. I studied these things as if they were landmarks on the road map to becoming a person I wanted to be: someone who could move through the world with such grace, and swag, and curiosity.

On a list of my heroes, it’s fair to say he is the only male. But the fact that he was a man and I was not didn’t bother me; his lack of pretension seemed to transcend masculinity or femininity.

When other people were thinking about sensible things to do after university, I was thinking about how I could get as far away as possible from the country I grew up in, America—and write about it in the process. I moved to London—which seemed somehow closer to the rest of the world—and worked a dozen shitty restaurant, temp, and hostess jobs, interned at magazines and freelanced. I lived in closet-sized bedrooms, and was broke a lot. I almost gave up a million times.

But each time I managed to do the thing—to write a story in an unfamiliar place, to learn some truth that helped me better understand the world—I knew I was on the right track. So I kept going. Looking through the writing of my 20s, there are so many pieces that I can directly attribute to Bourdain’s inspiration.

When I landed in Vietnam, on a two-month solo trip through Southeast Asia, I felt strangely as though Bourdain was with me. It was his favorite country. I was reporting a story for the Guardian about the hidden economics of Ho Chi Minh City’s street food when I wound up in the home of the proprietors of a popular lunch stall, with my fixer and photographer. My stomach was ravaged from something I’d eaten the day before, but when my hostess graciously offered me a shrimp fritter and fried chicken at 9:30 in the morning, I accepted it gladly and forced it down (along with some Tums). I know Bourdain would’ve done the same.

A few months ago, I got an email from an editor at Explore Parts Unknown, the website which served as a partner to his CNN show. They wanted to include a story I’d written in 2014 from Soweto, South Africa, about a subculture of precocious fashion-obsessed teenagers called izikhothane. I’d fought hard for that story during the writing process. The US editors who had commissioned it wanted me to highlight the stark poverty of its subjects. But what had struck me during my reporting was their outsized humanity.

I pulled the story from the original magazine that commissioned it, and scrambled to get it published elsewhere. It was a huge risk financially and professionally, but I knew that to travel all that way, do all that work, and not honor the spirit of the people who had let me into their lives was to miss the whole point. That was not the thing. As a writer, the fact that it was good enough to be part of Parts Unknown is one of my proudest moments to date.

There’s a moment on every trip I love. It’s the end of the first day, still jetlagged and with that weird clammy film all over your body from traveling. That’s when I find a bar with outdoor seating, ask for whatever the cheap, local lager is (they always taste the same, no matter where you are), and sit down to watch the evening hum by. From now on, I will drink a silent toast to Anthony Bourdain each and every time.