Graphic novels are novels. Five any literate person should read

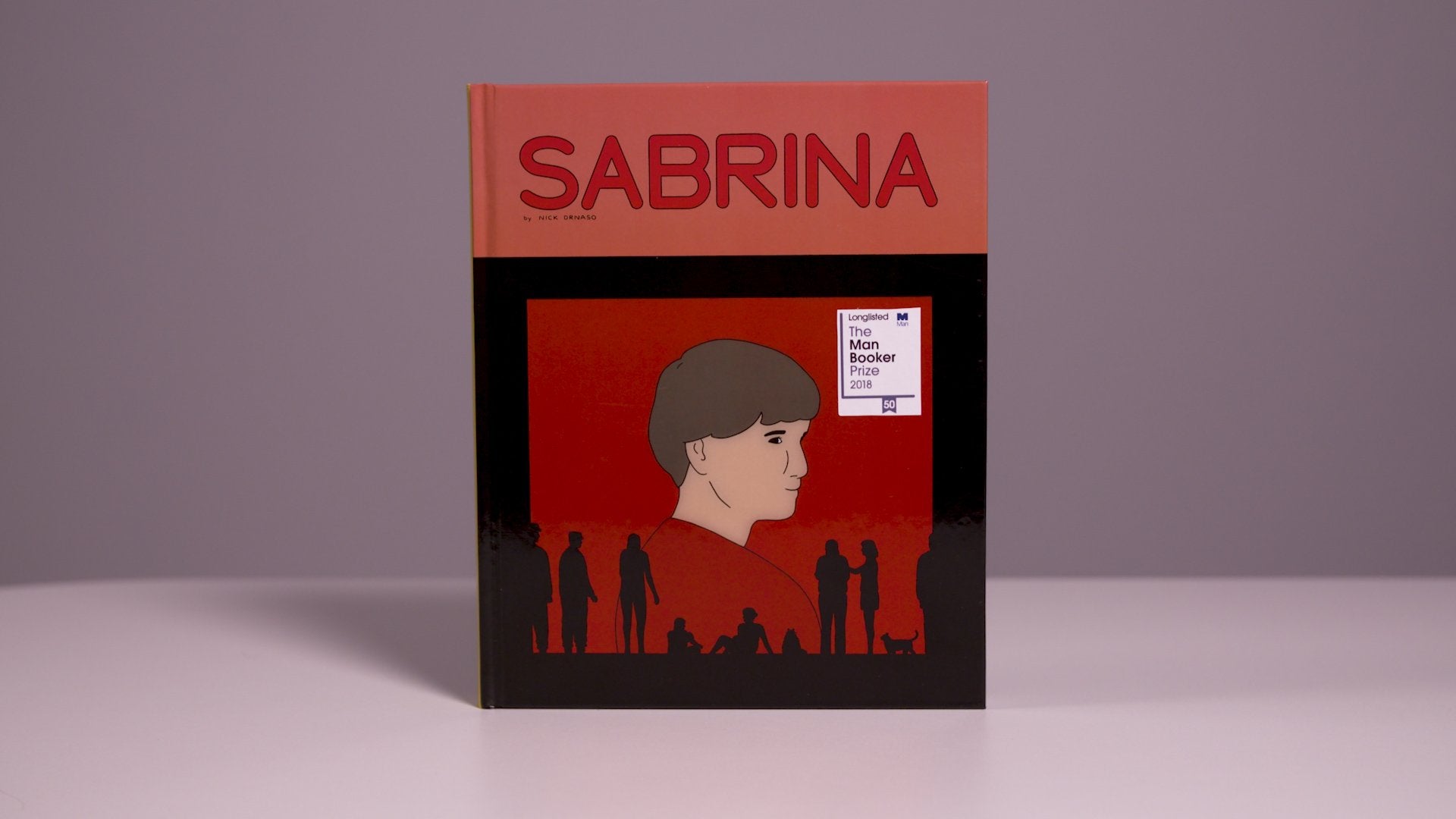

Following the announcement that Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina is the first graphic novel ever to be longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, Joanne Harris (the author of Chocolat) tweeted #TenThingsAboutGraphicNovels and stated simply: “graphic novels are novels.”

Following the announcement that Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina is the first graphic novel ever to be longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, Joanne Harris (the author of Chocolat) tweeted #TenThingsAboutGraphicNovels and stated simply: “graphic novels are novels.”

Once upon a time, graphic novels may have been viewed as disposable—and not especially literary—but such a value judgement has long since been challenged.

The graphic autobiography has become especially visible in recent years, with a noteworthy example being Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (2000)—which details her experiences as a young woman during and after the Iranian revolution in 1979. The novel was adapted into a film in 2007.

The comic book has a long and rich history, as Scott McCloud’s 1993 book Understanding Comics explains. He looks at a pre-Columbian text from the Codex Nuttall about 8-Deer “Tiger’s Claw”, discovered by the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortés around 1519. McCloud argues we can think about such early texts as comics.

Terminology is important here, too. The word “comics” usually refers to serialized publications—whereas “graphic novels” are issued as books. That said, they share many artistic and literary characteristics. Author Alan Moore has rejected the term “graphic novel” (along with the film versions of his work), suggesting it is nothing more than a marketing term. So, in no particular order—and with that caveat in mind—here are my top five literary reads in graphic novel and comic book genres.

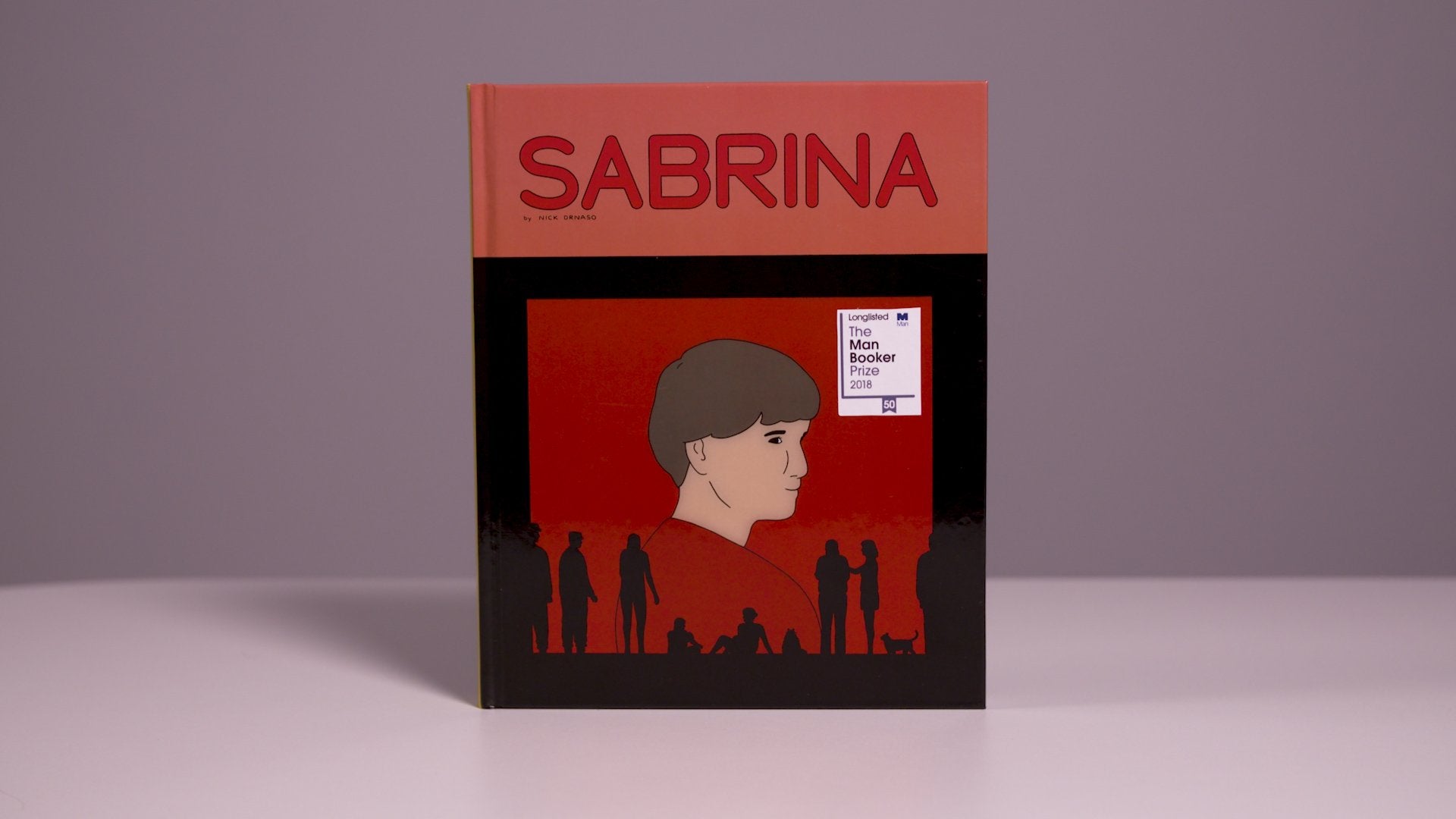

Grandville

(2009)

Author Bryan Talbot is well-known to comic and graphic novel fans, having penned The Adventures of Luther Arkwright in the 1970s and 1980s. Grandville is the first volume in a series of five, which tells the investigative story of a badger detective, Detective Inspector LeBrock, accompanied by his trusty sidekick, Roderick the Rat.

In this anthropomorphic universe, humans feature in servile roles as an underclass, with some critical comparisons to post-9/11 racial stereotypes. The Grandville of the title is an alternative history Paris, lovingly characterized with steampunk details and Belle Époque style. The city of Grandville takes its name from the pseudonym of a French artist, Gérard Grandville, famed for his satire of French politics and society.

The book wears its intellectualism lightly—but, for those with a keen eye, look out for cultural references to Édouard Manet, Augustus Egg, Sarah Bernhardt, and intertexts such as Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, as well as children’s classics including Wind in the Willows, Tintin and Rupert the Bear.

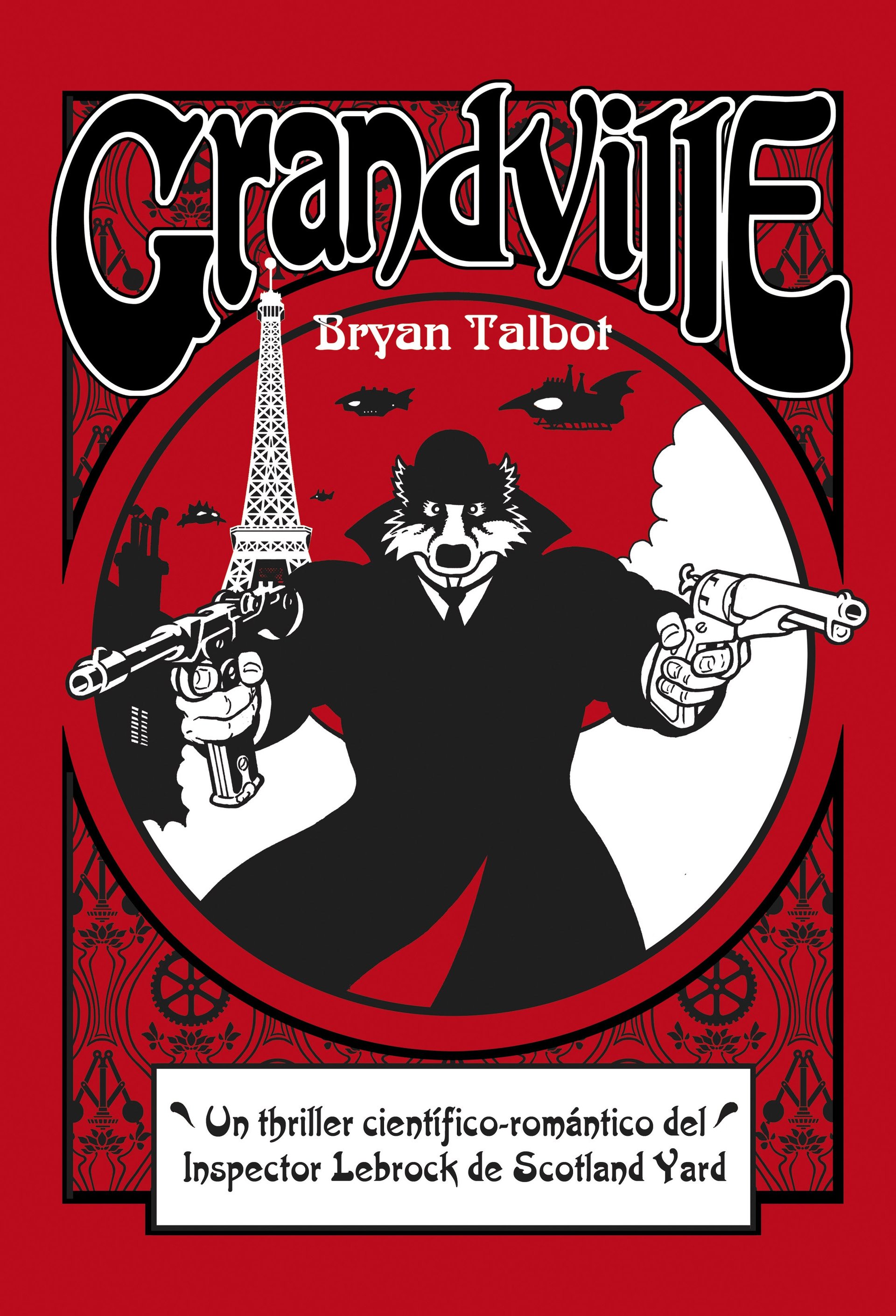

From Hell

(1999)

Alan Moore needs little introduction to cult readers or the academic community. He has amassed a wealth of literary criticism about his work, including plenty of material about the title I have chosen, From Hell. This was originally issued in serial form and later published as a single-volume collected work—the version with which most readers will be familiar.

From Hell is not for the squeamish: it retells in gruesome detail the Whitechapel murders of the late 19th century, speculating Jack the Ripper was Sir William Gull, Queen Victoria’s royal physician. Gull’s murder spree, seeking to suppress an illegitimate heir to the throne and filtered through a lens of masonic imagery and misogyny, takes us through a psychogeographic tour of London.

Eddie Campbell’s exquisite illustrations contrast the privileged suburbs in which Gull lives with the poverty-stricken degradation of Whitechapel’s citizens.

Partly fictional and partly factual, the book is a wonderful parody of the dark tourist interest in the murders, with the careful reader becoming increasingly self-conscious of their own uncomfortable complicity in the narrative.

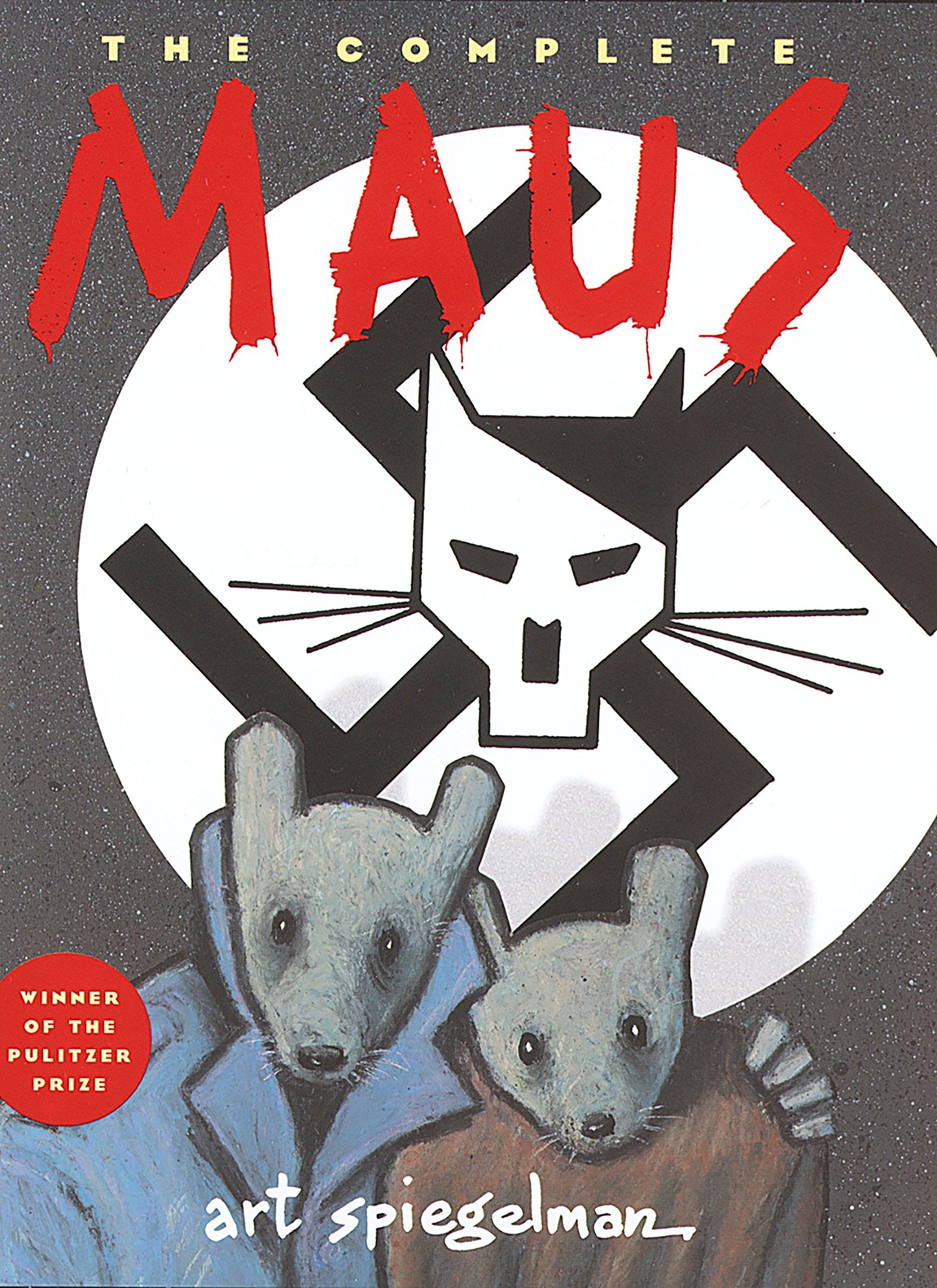

Maus

(1991)

Like From Hell, Art Spiegelman’s Maus was originally published in serial form. Spiegelman began writing in 1978, telling the story of his father, Vladek Spiegelman, a Holocaust survivor.

In many ways, the text defeats simplistic categories and genres: It is a fiction, an autobiography and a history.

It is also another anthropomorphic story in which Nazis are cats and the Jewish community are characterized as mice. The reader is placed in the unenviable but important position of bearing witness to the trauma of the Nazi regime, a point enhanced by the use of literary devices such as the framing narrative.

Spiegelman uses the more recent moment of the late 1970s and interviews with his elderly, widowed father as a departure point to revisit the 1930s through to the end of the Holocaust in 1945.

Spiegelman’s book won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992.

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage

(2015)

Sydney Padua’s witty black-and-white graphic novel describes itself as “an imaginary comic about an imaginary computer.” It foregrounds Ada Lovelace’s contribution to Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine, the herald of our modern computers.

Like other examples here, the narrative is situated in an alternative universe, which offers a view of what would happen if the Difference Engine had been built. Along with an adventure plot, the graphic novel features references to a wealth of 19th–century characters such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the Duke of Wellington. It has elaborate pseudo-factual footnotes and endnotes of which writers such as Flann O’Brien or Mark Z Danielewski would be proud.

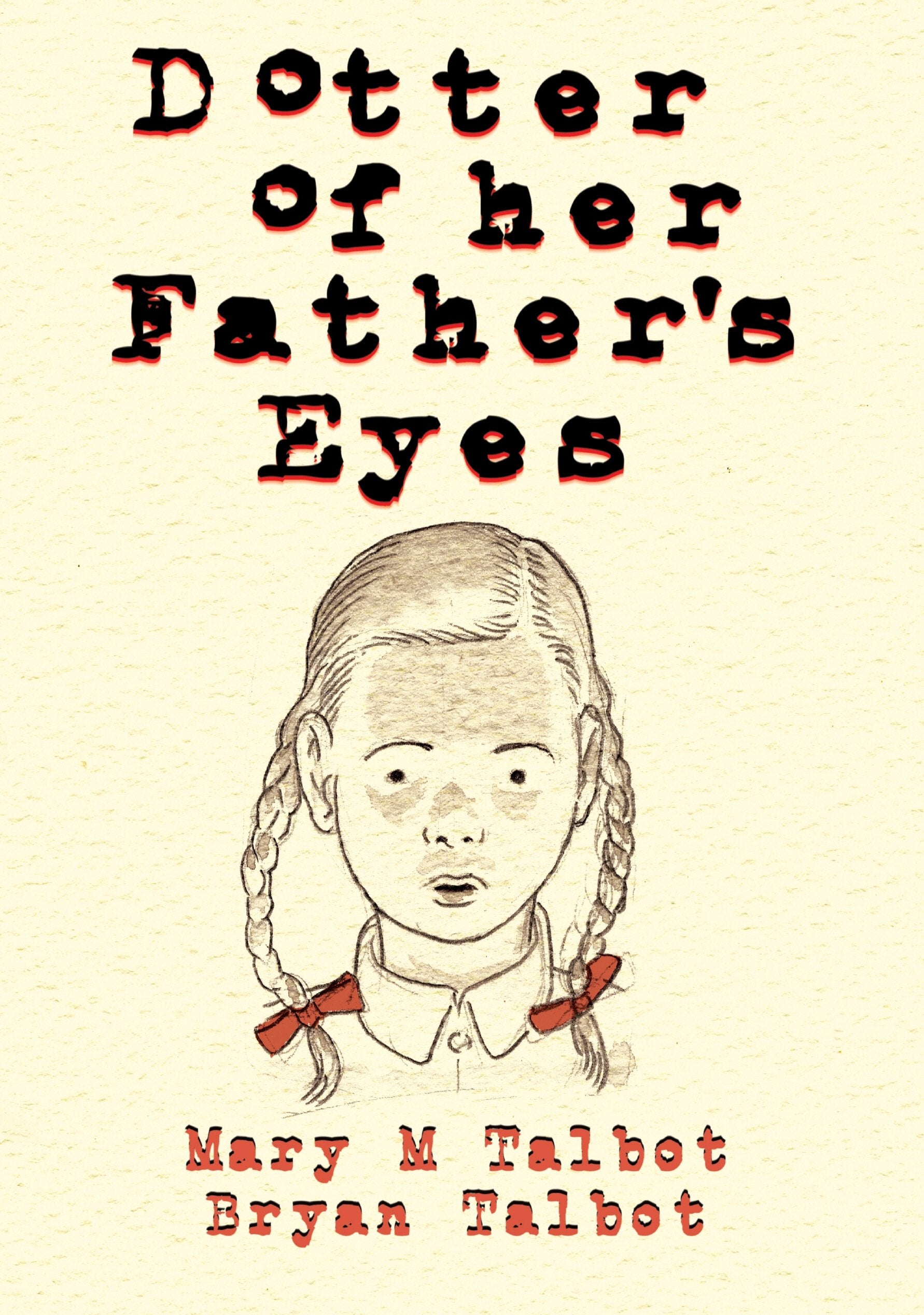

Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes

(2012)

It would be very remiss of me, as a longstanding aficionado of James Joyce, to omit reference to this Costa award-winning graphic memoir by Mary M Talbot (with illustrations by Bryan Talbot, the writer’s husband), which follows Lucia Joyce’s troubled relationship with her father, and draws parallels with the author’s own relationship with her father, the eminent Joyce scholar James S Atherton.

Lucia’s tragic love for Samuel Beckett—and her thwarted ambition to become a dancer—are beautifully juxtaposed with Talbot’s recollections of her upbringing, alongside the difficulties experienced by both talented women growing up with writerly fathers. Strategic use of colour, sepia tones and the frequent use of the Courier typeface (as well as Talbot’s own personal lettering font which features throughout his work), make this book an aesthetically delightful read.

So many masterpieces, so little time

Of course, there are many artists and writers I have omitted from this list—not least figures such as Neil Gaiman, whose work The Sandman (1989-) has been critically acclaimed, pushing as it does the Gothic tropes and metaphysical reflections of the genre.

For those of a humorous inclination, Kate Beaton’s webcomic Hark, A Vagrant (published as a book in 2011) is an affectionately irreverent look at literature and history, including the hilarious Dude Watchin’ With the Brontës.

There are also the recent works lauded in the Will Eisner Comic Awards, held earlier this month in San Diego as part of Comic-Con. Further reading can be found on that list.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.