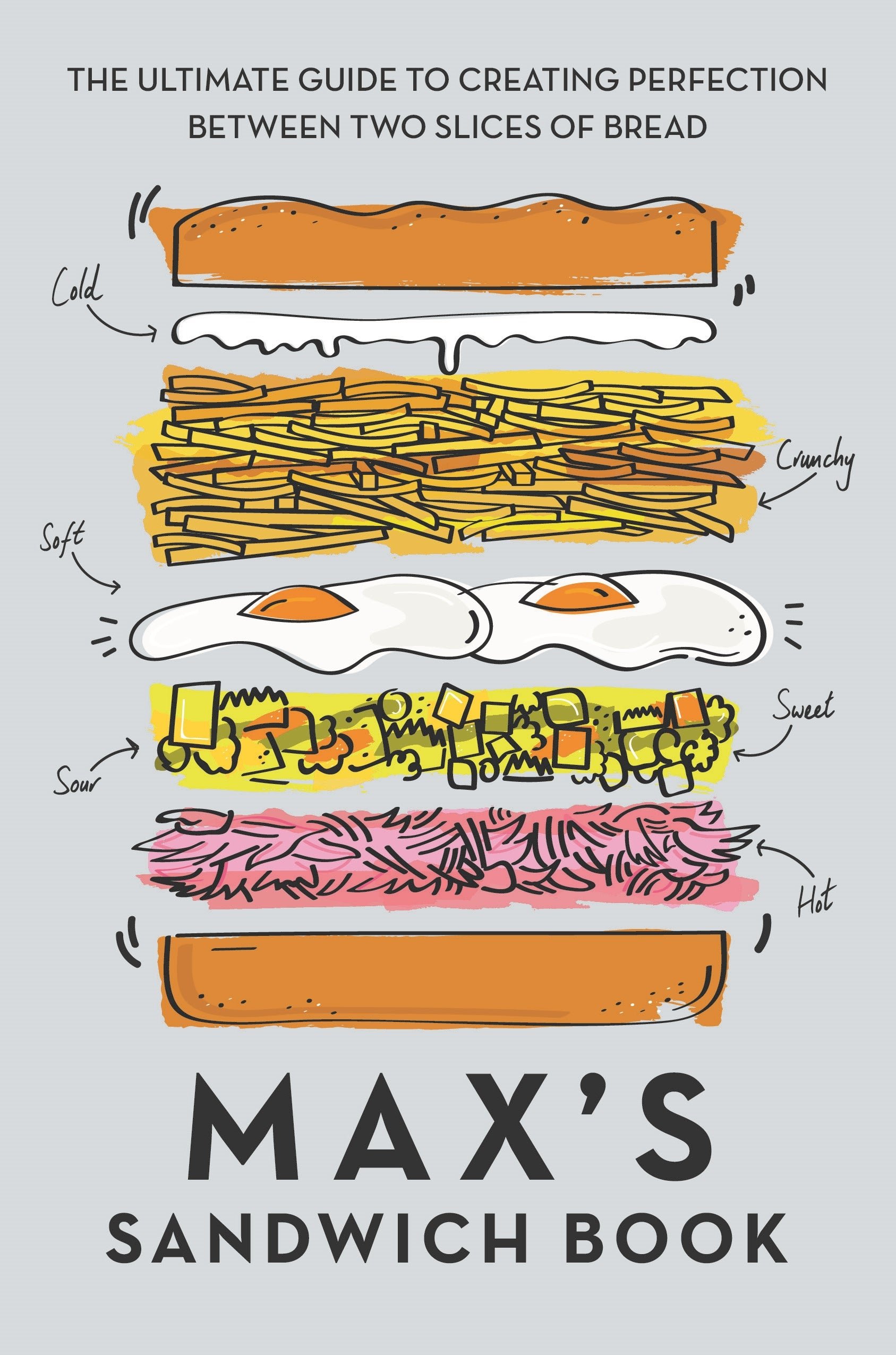

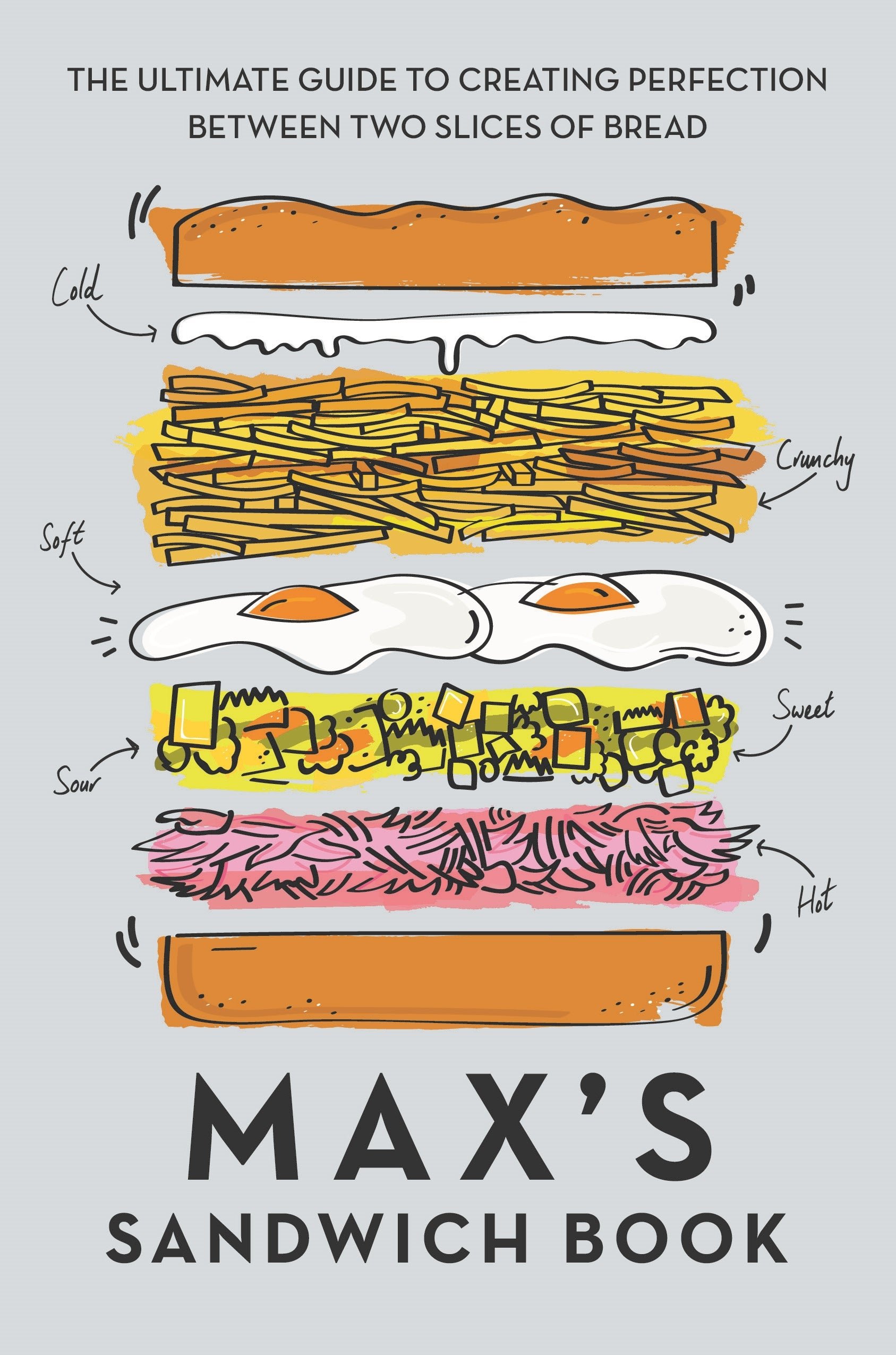

The six-point formula for a perfect sandwich

To hear Max Halley talk about a sandwich is to witness a full-throated defense of the thing as a serious culinary undertaking, not a lowly lunchtime convenience food.

To hear Max Halley talk about a sandwich is to witness a full-throated defense of the thing as a serious culinary undertaking, not a lowly lunchtime convenience food.

To prove his point, the British chef and author opened Max’s Sandwich Shop in northeast London’s Stroud Green four years ago and decided it would only be open in the evenings. You know, for dinner.

Before he opened, he asked a couple dozen of his chef and restaurant industry friends—he formerly worked for the UK-based Spanish food importer Brindisa as well as London’s Michelin-starred Arbutus—to draw up lists of their favorite sandwiches.

“It was all BLT, egg and cress, cucumber and Marmite—all lunchtimey. Your sausage might be hot, but it’s a fucking breakfast sandwich,” Halley said. “I just got slagged off by people—people in the industry, my mom—saying it’s never going to be anything beyond lunchtime.”

So how, exactly, did he manage to elevate the humble midday sarnie into something to look forward to for dinner? “Hot cold sweet sour crunchy soft,” Halley breathlessly rattles off, as if reciting a religious mantra. “It’s the secret of delicious.”

This six-point formula is the basis of every smorgasbord of a sandwich on the Sharpie-scribbled menus at Max’s Sandwich Shop, from the classic “Ham, Egg ‘n’ Chips”—slow-cooked ham hock, a fried egg, piccalilli, malt vinegar mayo, and a portion of house-made shoestring fries that is way more than a garnish—to the “Et Tu Brute? Murdering the Caesar,” which comes with roasted guinea fowl, pickled grape and tarragon salsa, baby gem, chicory, anchovy mayo, and garlic croutons. (Of the croutons, Halley proudly says: “People said you couldn’t put bread in a sandwich—but they didn’t think about deep frying it.”)

Halley is quick to point out that he doesn’t claim the six-point philosophy as his own—”any great plate of food should be like that”—but he is, perhaps, the first British chef to apply it to the sandwich with such zealous commitment.

“On a regular plate of food, the chef can’t control the order in which you eat everything, so each mouthful is different and each mouthful has a bit more of this and a bit less of that,” Halley said. “Whereas, in the context of a sandwich, you are getting all six of those elements into every mouthful. The advantage that I have as a chef [making a] sandwich is that I can control how it’s eaten.”

In a country like Britain, where the so-called “high street sandwich” is as ubiquitous and unremarkable as a cup of tea, convincing diners that a sandwich is more than just a convenience food takes effort. As journalist Sam Knight wrote in his near-anthropological exploration of the British triangular sandwich last year, “The homeliness of the sandwich has been able to mask its extraordinary effectiveness as a commercial product.”

“There’s nothing wrong with an egg and cress, my problem is with what the triangular sandwich has become,” Halley says. “These now are literally things of convenience, and it is not convenient for us—it’s convenient for [British supermarket chain] Sainsbury’s. I don’t like the receding of deliciousness.”

To encourage diners to take his maximalist sandwich philosophy home with them, Halley co-authored a book with his business partner and fellow chef Ben Benton, which was published in May. He hopes that, in addition to giving readers an enhanced appreciation of, say, mixing bacon fat into your mayonnaise or including Scampi Fries—a packaged pub snack—in your fish finger sandwich, they can encourage readers to look at the concept of leftovers differently, too.

“Together, Ben and I would like to encourage just generally, the idea of making a delicious dinner for tonight, with a sandwich in mind for tomorrow,” Halley writes.

Though they are both founded on the same six-component formula, the sandwich shop and the book serve different purposes, Halley says. The former is to simply delight people—while providing a somewhat sophisticated culinary experience that’s “masquerading as a silly sandwich shop.” The latter is to help people realize that, with slight adjustments and a little attention to detail, they can elevate the same old ingredients in the pantry or from the corner shop into something rather more delicious.

“You should ask yourself two questions: Can I deep fry that? And can I mix that into mayonnaise? These are life lessons.”