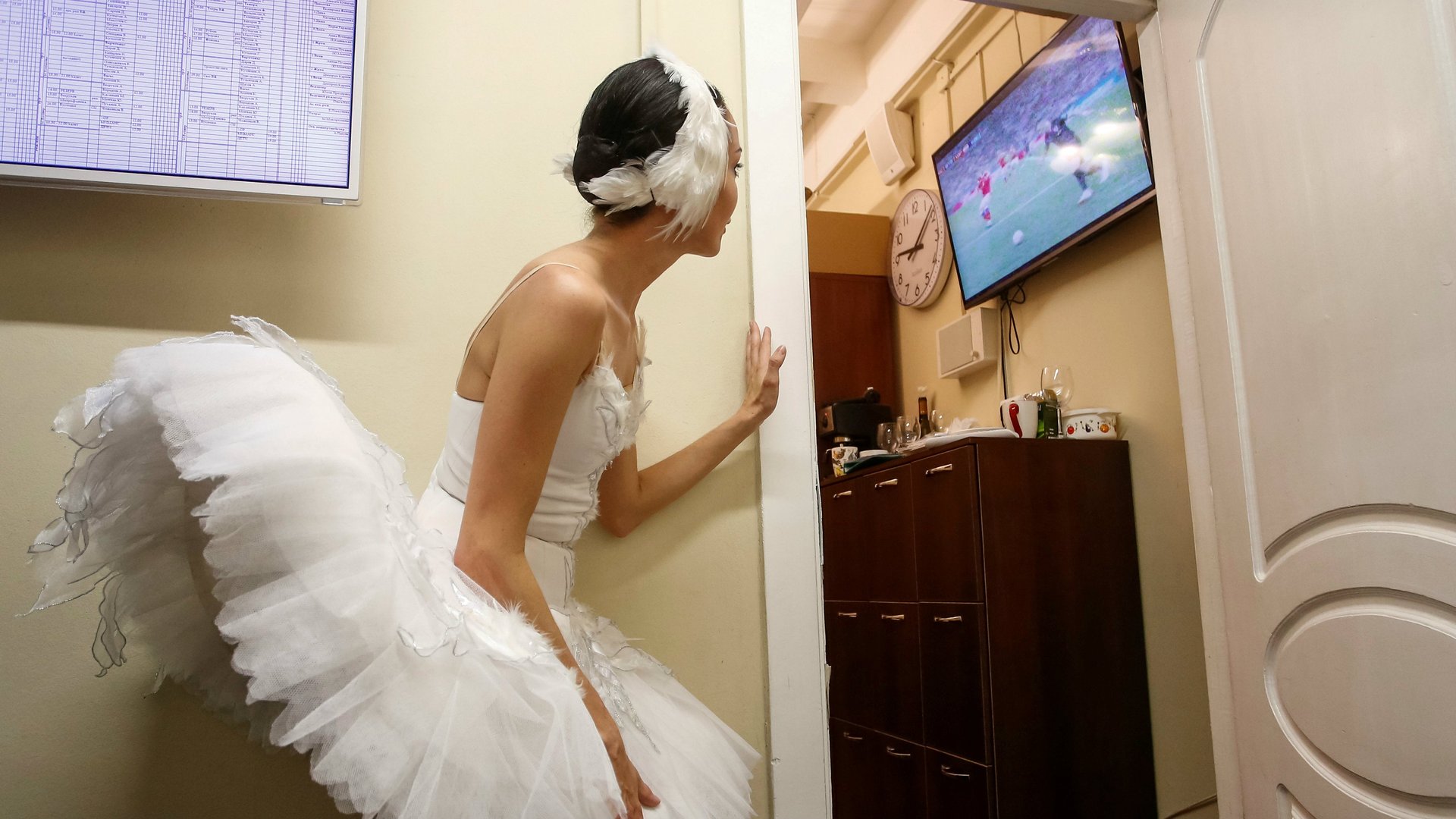

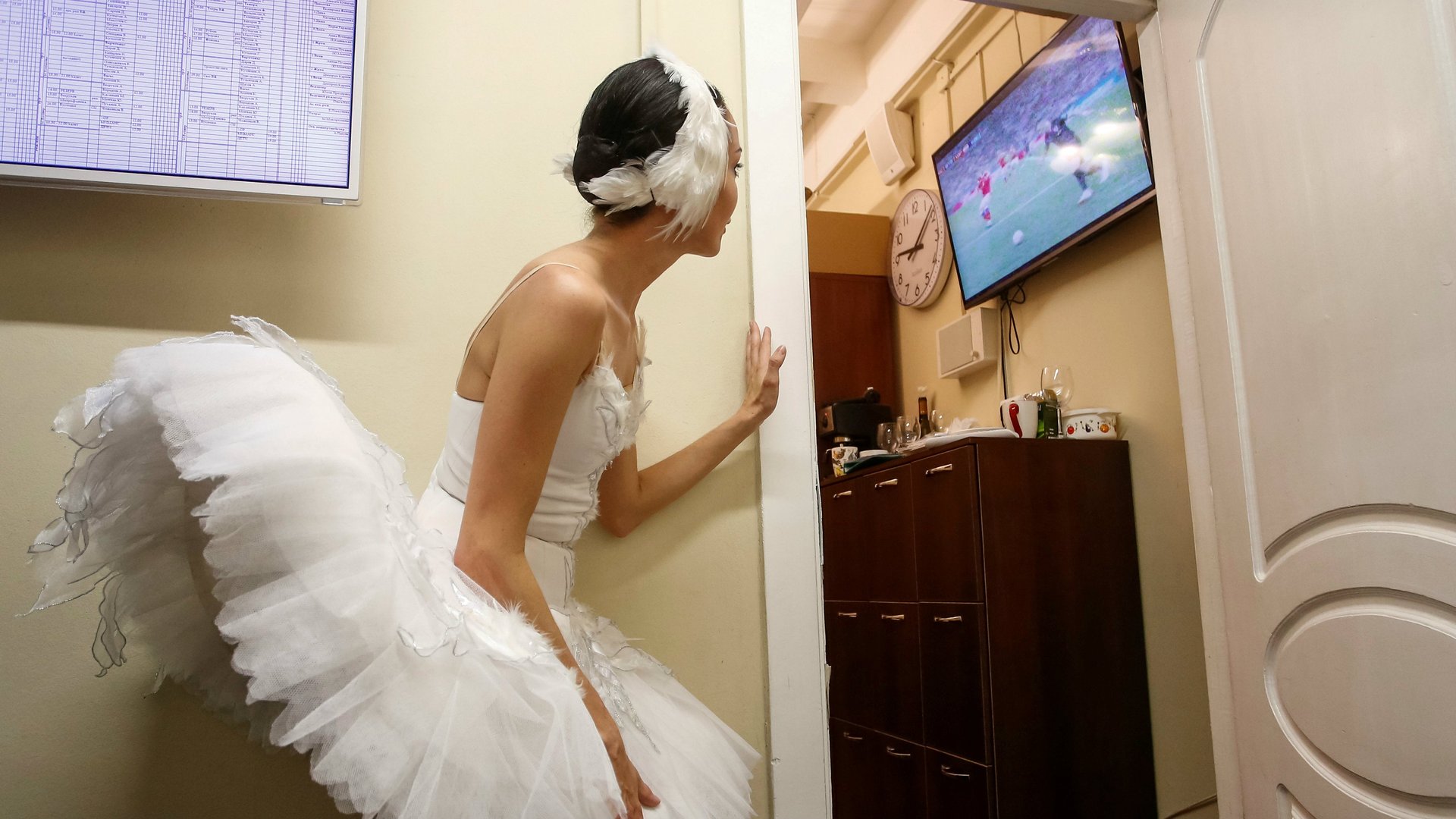

Revel in the joy of doing things you will never master

When was the last time you went for a walk? You know, just a walk. Not one intended to get you anywhere, not a brisk half-jog intended to make you fit, not even one with the fuzzy goal of procuring a caffeinated beverage: Just a walk.

When was the last time you went for a walk? You know, just a walk. Not one intended to get you anywhere, not a brisk half-jog intended to make you fit, not even one with the fuzzy goal of procuring a caffeinated beverage: Just a walk.

And if you did, did you tell anyone about it? Did you hope to have a better walk than the one you had last week? Probably not because, well, that’s the thing about a walk: It may be pleasant, but it’s not really an achievement—it just is.

In our precarious version of late capitalism, we have become an obsessively goal-oriented society. As my colleague Thu-Huong Ha wrote recently, we can scarcely read a book without attaching rigid, performance-oriented goals to it. Our side-hustles, multi-hyphenate career paths, Instagrammable creative projects, and personal branding opportunities are seemingly embedded in every hobby, pursuit, and hour of spare time. In a world of uncertainty, it can sometimes feel like we’re all trying to “do” our way out of existential dread. And so we’ve forgotten there is also the joy of being thrilled in the moment, without trying to accomplish anything at all.

This attitude extends from the prosaic Sunday walk to creative pursuits. As author Elizabeth Gilbert explained to Krista Tippett in a 2016 episode of the public-radio show and podcast On Being, our culture can make us feel that creative pursuits are only worthwhile if they’re attached to some goal of fame, fortune, or recognition:

I wrote some poems recently and a friend of mine who’s a songwriter, I showed them to her, and she said ‘We should turn these into songs and you should sing them.’ … And so I sat in a studio for an afternoon with five friends who are musicians and we recorded a song. It was so cool that this thing hadn’t existed and at the end of the day, it did. There was something so wonderful and collaborative and joyful about it. And the next day I was at a meeting in New York and I mentioned to someone I was in the recording studio making a song over the weekend and they said ‘What’s it for?’ And it’s such a great question, I thought ‘What’s it for?’ Even I stammered and said “it’s for joy and becoming and unfolding and communion.” It wasn’t the greatest song that anyone ever made but nobody died from it.

Too often, we don’t start pursuits unless we can master them. We think if we don’t finish the watercolor painting, progress from downward dog to headstand, or walk the full 10km of the hike, then something bad will happen—so we shouldn’t bother trying. Conversely, we assume if we do finish those things, something good will happen. And yet usually, the outcome is neutral. The value of those pursuits is literally in the time we spend doing them, not in their payoff on the other side.

That is not to say that goals aren’t effective motivators, and people who set and meet them don’t feel satisfied. Indeed, in my own life, I have plenty of goals and no shortage of ambition for my professional life. But as someone who used to construct an entire identity in being perfect at every single thing I tried—and not daring to try anything I wouldn’t be good at—I’ve found freedom in accepting that doing things because they feel good in the moment is perhaps as good a guiding rationale for my life as anything else. This can be as simple as stopping a run just shy of a 5k to more fully enjoy the way the light is hitting the trees, or doing a less-intense (and less impressive-looking) version of a yoga pose simply because it feels better that way.

It’s true that this neutrality towards the outcome is necessarily the opposite of how most of us live our career and personal lives, and for good reason. We need to care about our work, and our relationships, and the consequences of our aggregate actions over time. And indeed, mastery of a skill or craft—whether that happens to be tied to a salary, or not—can be immensely satisfying over a lifetime.

But what we don’t need to do is make sure that every single thing we spend our time on has a measurable and quantifiable outcome. We don’t need to have ambitions to become master potters to take a pottery class, or have a gig in two weeks to spend an afternoon strumming the guitar, or a plan to run a marathon to enjoy a run round the park. We can dabble, meander, dip our toes in projects they have no business being in—and not feel the need to tell anyone about how much we did or didn’t accomplish.

While the internet economy has given people great freedom and opportunity to work beyond their day job and create careers in the margins of a normal life, it’s also added a pressure to achieve something more impressive than just being a person who quietly enjoys your life. I say: Don’t bow to it. As my yoga teacher said recently, your foot may get there, or it may not. The outcome doesn’t matter. The doing does.