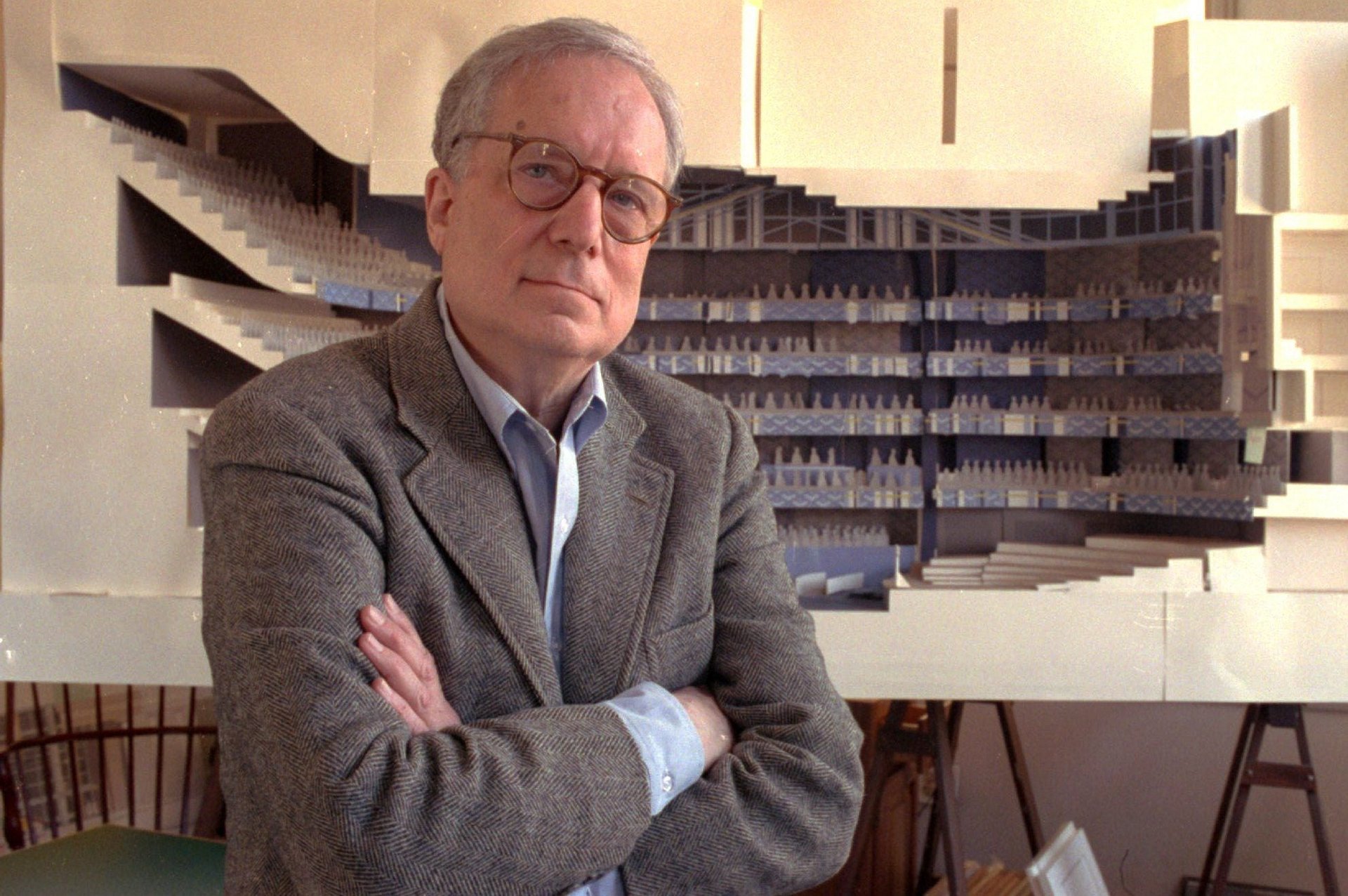

Robert Venturi changed the course of architecture history with the design of his mom’s house

Robert Venturi shattered the modernist box—with a little help from his mother.

Robert Venturi shattered the modernist box—with a little help from his mother.

The influential American architect and co-author of the “gentle manifesto” against modernism passed away this week due to complications from Alzheimer’s disease. He was 93.

In the 1960s, Venturi and his wife and business partner Denise Scott Brown paved the way for postmodernism (at times referred to as POMO), an architecture philosophy that rejected the rigid austerity of the International Style propagated by Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, and their acolytes.

Tired of the formalist mandate that dictated templates for modern buildings, the duo championed the “messy vitality” of buildings and cities. Venturi first demonstrated the rich possibilities of POMO in designing his mother’s house in Philadelphia—a project that he labored over for six years. Newly widowed at 76, Vanna gave her son free reign to design her house. No timelines, no restrictions, just a “simple and unpretentious home with most rooms on one level and no garage.”

Completed in 1964, Venturi’s mom’s retirement home included elements that reversed modernism’s rules. For one, it was purposely asymmetrical. The façade had mismatched windows and Venturi oriented the dramatic gable along the building’s length, which made it look distorted. (The gable or pediment roof is typically positioned on the short side of a house.) Inside the five-bedroom house were irregularly shaped spaces and rooms arranged like a city grid. The house contained whimsical elements, too, like a flight of stairs that led to a wall.

The front and back of the house were also completely different. “You get the Queen Anne front and the Mary Anne behind,” said Scott Brown. “Or you could say Michelangelo and suburbia on the front, and Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto at the back.”

Venturi used historical elements to break the house’s plain surface. To mess with rational modernists, he added an arch that didn’t frame the door. He also chose the house’s pale green color as a foil to Bauhaus-trained designer Marcel Breuer‘s edict that one should never paint a house green. It was pure defiance—Venturi says that the oversized chimney was a middle finger to the establishment.

“This building is complex and simple, open and closed, big and little. Inside and out, it is a little house that uses big scale to counterbalance the complexity,” he explained, hinting at a philosophy that he would expound on in his 1966 book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. The slim volume, along with Learning from with Las Vegas, co-authored with Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, would provide the intellectual foundation for postmodern architecture.

Several scholars point to Vanna Venturi’s house as the first postmodern structure in the US—a building that would influence an entire generation of architects like Philip Johnson, Aldo Rossi, Michael Graves, and Frank Gehry. Venturi was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 1991. The committee behind the architecture industry’s highest honor famously rejected Scott Brown’s request to be recognized as his equal creative partner.

Throughout their career, Venturi and Scott Brown would gain several prominent commissions such as the Seattle Art Museum, the Philadelphia Orchestra Hall, a wing at the National Gallery, London. But Vanna Venturi’s suburban residence was the “embryo for everything,” Scott Brown told Dezeen.

In retrospect, Venturi said in a 2017 PBS interview that he didn’t intend to use his mother’s house as a manifesto. He was simply trying to make something more interesting than minimalist boxes. “I wasn’t trying to be postmodern,” he said. “Don’t trust an architect who’s trying to start a movement.”