The urge to share our lives on social media is neither new nor narcissistic

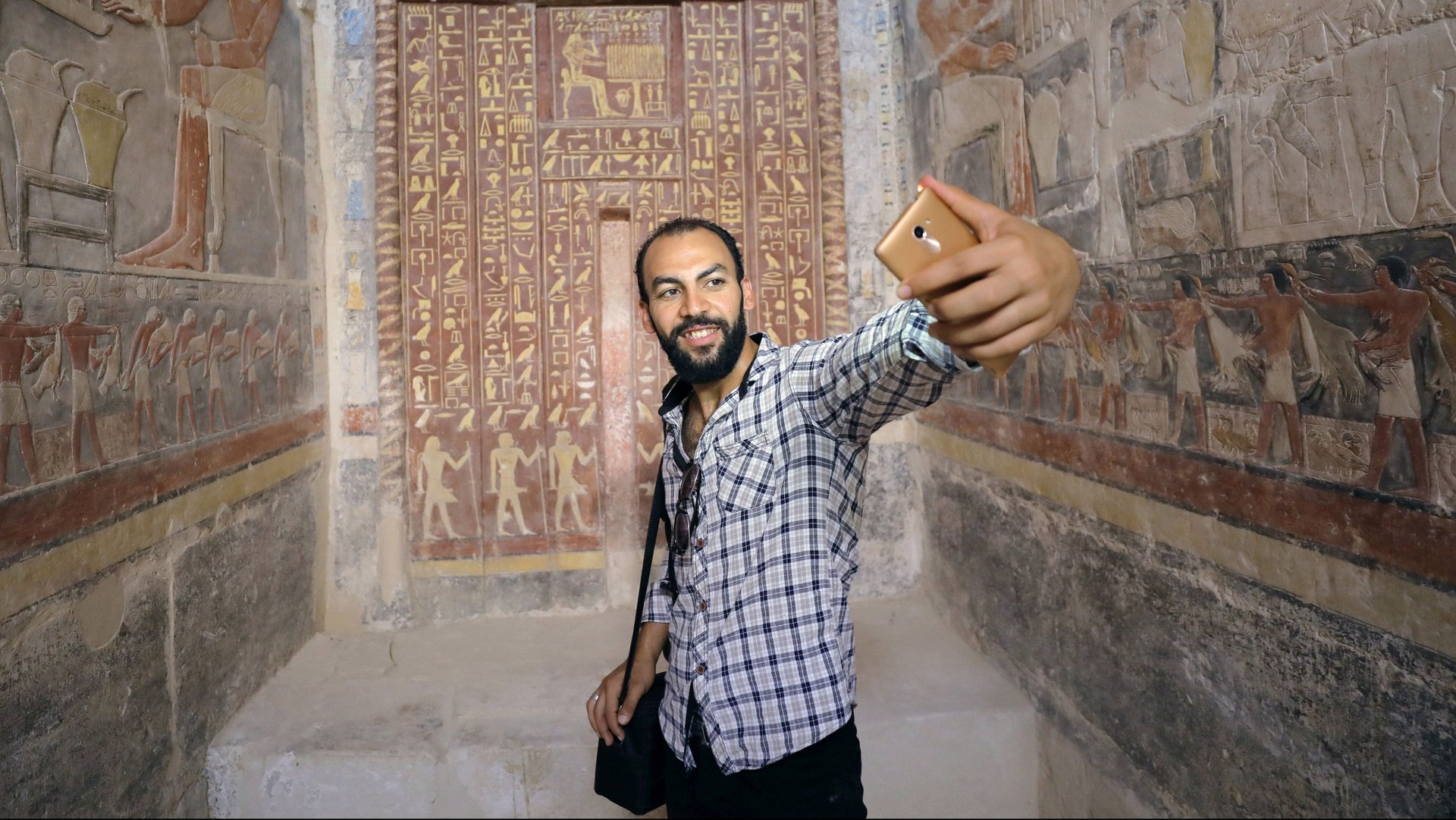

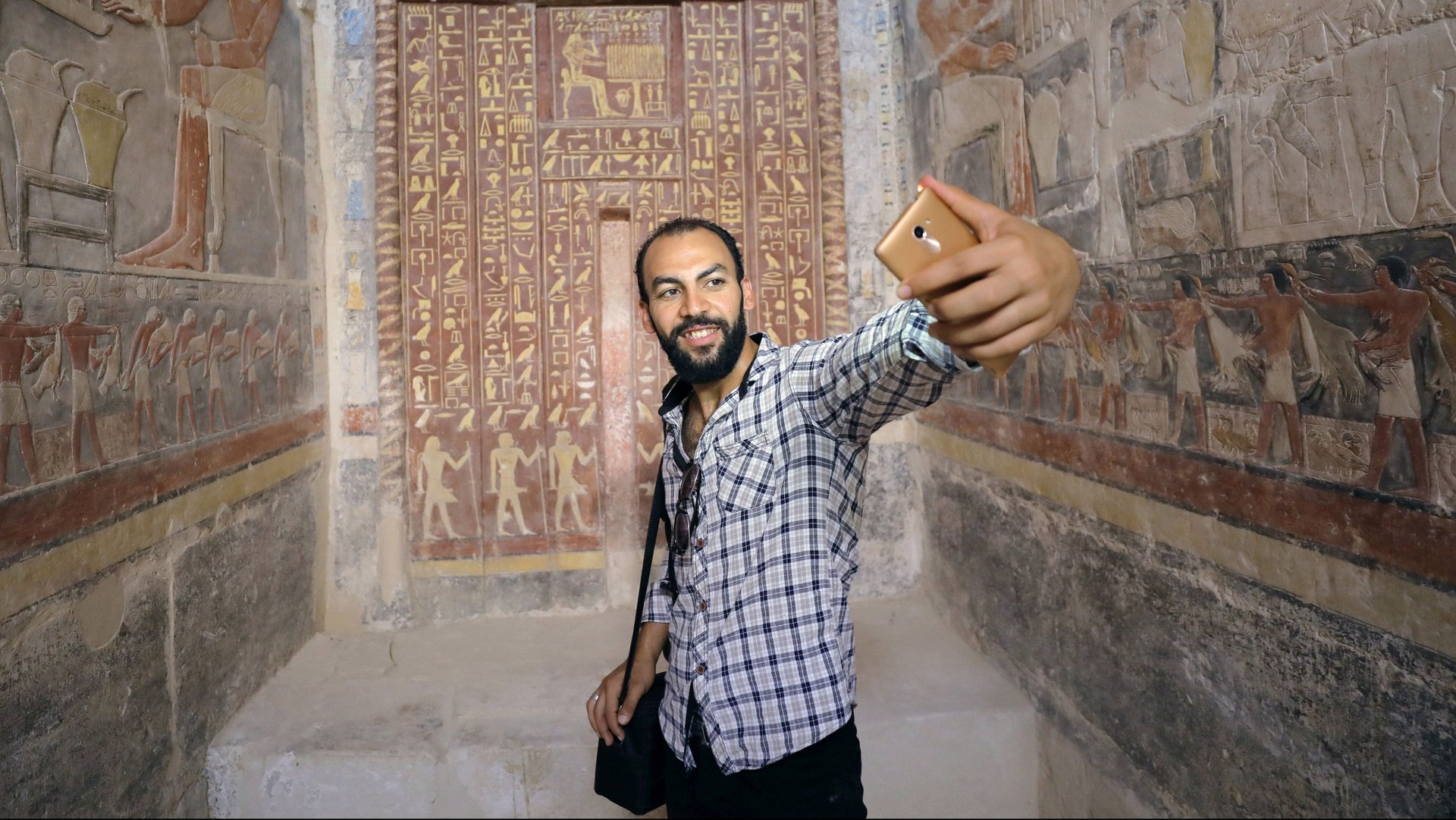

Narcissism is defined as excessive self-love or self-centeredness. In Greek mythology, Narcissus fell in love when he saw his reflection in water: he gazed so long, he eventually died. Today, the quintessential image is not someone staring at his reflection but into his mobile phone. While we pine away for that perfect Snapchat filter or track our likes on Instagram, the mobile phone has become a vortex of social media that sucks us in and feeds our narcissistic tendencies. Or so it would seem.

Narcissism is defined as excessive self-love or self-centeredness. In Greek mythology, Narcissus fell in love when he saw his reflection in water: he gazed so long, he eventually died. Today, the quintessential image is not someone staring at his reflection but into his mobile phone. While we pine away for that perfect Snapchat filter or track our likes on Instagram, the mobile phone has become a vortex of social media that sucks us in and feeds our narcissistic tendencies. Or so it would seem.

But people have long used media to see reflections of themselves. Long before mobile phones or even photography, diaries were kept as a way to understand oneself and the world one inhabits. In the 18th and 19th centuries, as secular diaries became more popular, middle-class New Englanders, particularly white women, wrote about their everyday lives and the world around them. These diaries were not a place into which they poured their innermost thoughts and desires, but rather a place to chronicle the social world around them—what’s going on around the house, what they did today, who came to visit, who was born or who died. The diaries captured the everyday routines of mid-19th-century life, with women diarists in particular focused not on themselves but on their families and their communities more broadly.

Diaries today are, for the most part, private. These New England diaries, in contrast, were commonly shared. Young women who were married would send their diaries home to their parents as a way of maintaining kin relations. When family or friends came to visit, it was not uncommon to sit down and go through one’s journal together. Late 19th-century Victorian parents would often read aloud their children’s diaries at the end of the day. These were not journals with locks on them, meant only for the eyes of the diarist, but a means of sharing experiences with others.

Diaries are not the only media that people have used to document lives and share them with others. Scrapbooks, photo albums, baby books, and even slide shows are all ways in which we have done this in the past, to various audiences. Together, they suggest that we have long used media as a means of creating traces of our lives. We do this to understand ourselves, to see trends in our behaviour that we can’t in lived experiences. We create traces as part of our identity work and as part of our memory work. Sharing mundane and everyday life events can reinforce social connection and intimacy. For example, you take a picture of your child’s first birthday. It is not only a developmental milestone: the photo also reinforces the identity of the family unit itself. The act of taking the photo and proudly sharing it further reaffirms one as a good and attentive parent. In other words, the media traces of others figure in our own identities.

By comparing old technologies with new technologies that enable us to document ourselves and the world around us, we can begin to identify what is really different about the contemporary networked environment. Building on a 20th-century broadcast model of media, today’s social media platforms are, by and large, free to use, unlike historical diaries, scrapbooks, and photo albums, which people had to buy. Today, advertising subsidises our use of networked platforms. Therefore these platforms are incentivized to encourage use of their networks to build larger audiences and to better target them. Our pictures, our posts, and our likes are commodified—that is, they are used to create value through increasingly targeted advertising.

I don’t want to suggest that, historically, using media to create traces of ourselves occurred outside of a commercial system. We have long used commercial products to document our lives and to share them with others. Sometimes even the content was commercialised. Early 19th-century scrapbooks were full of commercial material that people would use to document their lives and the world around them. It’s easy to think that once you buy a journal or scrapbook, you own it. But, of course, the examples of sending diaries back and forth, or of Victorian parents reading their children’s diaries aloud, complicate notions of historical singular ownership.

Commercial access to our media traces is also historically complex. For example, people used to buy their cameras and film from Kodak, and then send film back to Kodak to be developed. In these cases, Kodak had access to all of the traces, or memories, of its customers but the company didn’t commodify these traces in the ways that social media platforms do today. Kodak sold customers its technology and its service. The company didn’t give it away in exchange for mining their customers’ traces to sell ads targeted at them in the way that social media platforms use our traces to target us today.

Instead of social media merely connecting us, it has become a cult of notifications, continually trying to draw us in with the promise of social connectivity—it’s someone’s birthday, you have a Facebook memory, someone liked your picture. I’m not arguing that such social connectivity isn’t meaningful or real, but I believe it’s unfair to presume that people are increasingly narcissistic for using these platforms. There’s a multibillion-dollar industry pulling us into our smartphones, relying on a longstanding human need for communication. We share our everyday experiences because it helps us to feel connected to others, and it always has. The urge to be present on social media is much more complex than simply narcissism. Social media of all kinds not only enable people to see their reflections, but to feel their connections as well.

This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.