Apple’s new bagel emoji tells a sad story of automation gone wrong

Mangoes, molars, mosquitos and mooncakes: All these things will soon become expressible on your device in a picture-based form. With iOS 12.1, Apple is adding over 70 new emojis to its arsenal of around 240, allowing you to instruct your spouse to pick up more toilet paper, remind your babysitter about your child’s teddy bear, or nudge your colleague on those expense receipts without suffering the ignominy of spelling things out in actual words.

Mangoes, molars, mosquitos and mooncakes: All these things will soon become expressible on your device in a picture-based form. With iOS 12.1, Apple is adding over 70 new emojis to its arsenal of around 240, allowing you to instruct your spouse to pick up more toilet paper, remind your babysitter about your child’s teddy bear, or nudge your colleague on those expense receipts without suffering the ignominy of spelling things out in actual words.

But there’s a problem. Nestled among all these cheerfully bright images is a bagel. And it looks completely inedible.

Actually, it’s not even one bagel. It appears to be one and a half—a full bagel awkwardly perched on top of half a sliced bagel, in a configuration that seems implausibly pointless. The outside is tan; the inside is porridge-colored. It’s as homogenous as a Dunkin’ donut. A good bagel shouldn’t look like it came out of a factory, as any New Yorker knows—and it certainly shouldn’t look anything like a glazed donut.

As New York Magazine’s Grub Street reports:

The disappointment is truly overwhelming. Take a look at this clearly machine-cut monstrosity with its stiff and bready interior, which couldn’t possibly be redeemed by a few minutes in a toaster. And let’s talk about that distressingly smooth crust. What midwestern bagel factory did this bagel come out of? And is it really a bagel if there isn’t a disgusting amount of cream cheese that needs to be wiped off with a napkin before you can consume it?

Predictably, bagel-Twitter responded to the pixelated baked good with a howl of unrestrained contempt:

But the sad truth is, many actual bagels do resemble Apple’s computer-generated aberration. And the reason they do goes back decades, starting at a time when making bagels was a hellishly fiery and dangerous task. It’s the story of how automation brought the Jewish food to the mainstream—repackaged, repurposed and reconfigured for a general audience. And it’s a story that ends with stodgy, supermarket-friendly bagel pap, as depicted in this emoji.

What’s so special about bagels, anyhow?

First of all, why are New Yorkers and other bagel connoisseurs so obsessed with this bread product? How is it different from any other roll?

Making a really good bagel is more complicated than you might think. It’s not simply a hard-ish baked dough-ball with a hole in the middle. It requires many hours of kneading and shaping, “retarding” and proving, boiling and baking. In the days before bagel machines, handling the dough alone might take months to master.

Once shaped, the raw dough rings must sit for hours in a cool room, developing their flavor like a fine wine, rather than ballooning like a cottage loaf. They are then dipped into a great pot of boiling water for just under a minute, cooled and dried. Finally, they are baked.

If you don’t go through these steps, you might have something that is quite edible—but probably not actually a bagel. Each step is crucial to achieving a glossy crust, a “correct” chewy consistency, and that sour, lactic tang.

J. Kenji López-Alt of Serious Eats has a few rules for a good bagel. It should be eaten within half an hour of baking, shouldn’t need to be toasted, he writes, and should have “a thin, shiny, crackly crust spotted with…microblisters.” Other than plain, only a few flavors are acceptable: “everything”; salt; garlic or onion; poppy seed; egg; sesame seed; pumpernickel; cinnamon raisin.

Wondering about that last one? “I include cinnamon raisin in this lineup only because my wife likes to eat them with scallion cream cheese.” Cynthia Nixon would approve.

A history of dough, fire, and labor unrest

Like many immigrants, bagels made their entry to the United States in New York. It was the late 19th century, and the Jewish population soared as families fled the pogroms of their Eastern European homelands. There was a clamor for kosher food, which led to a boom in Jewish-owned food outlets and stalls, including challah- and bagel-selling bakeries.

These tended to be perilous underground establishments, infested with cockroaches and the cats that chased them. The ovens were coal-fired, with searingly hot open flames and vats of boiling water bubbling over. Apprentice bakers worked 18 hours a day, napped in the piles of flour, and tried to avoid losing their eyebrows in the scrum. Their customers, like them, were Jews.

In time, labor laws tightened. The Yiddish-speaking bakers formed a fearsome union with a high barrier to entry, occasionally plunging New York into so-called “bagel famines” in work stoppages during negotiations about their pay and benefits. Between the 1930s and 1960s, bagels went from an “ethnic food” to a New York staple.

In her book The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread, Maria Balinska cites a 1950 article from the Bakers and Confectioners’ Journal describing the hallowed New York City establishments in which bagels were made. Without machines of any kind, “walking into a bagel bakery gives you the feeling that you are entering another century…The air is thick with the flavor of the Old World, because modernism has no place in an establishment which produces this ancient Jewish bread product.”

By 1960, the Times reported, the city had become “the bagel center of the free world, and will doubtless be kept that way by the hundreds of thousands of residents who find that a bagel makes breakfast almost worth getting up for.”

The bagel of today

But between 1960 and the present day, a lot has changed. Modern bagels barely resemble their ancestors. The bagels of yesteryear were around half the size, had far fewer toppings, and would break your teeth if not consumed within a few hours of baking.

The change in the product has everything to do with the change in the process of making bagels. As a public taste for bagels grew beyond Jewish immigrant communities, technology and service innovations began to creep in. First, it was revolving ovens, increasing production rates and allowing customers to buy their bagels fresh from the flames. Next, it was freezers, allowing shopkeepers to sell yesterday’s bagels tomorrow—or in three weeks.

But the real death knell for the classic New York bagel came first from California (not unlike Apple’s bagel emoji). In the late 1950s, Daniel Thompson, a California math teacher turned inventor, created the “bagel machine,” which skipped many of the key steps, including being boiled. The rings of dough this contraption turned out weren’t crusty or tangy, but they did still have a hole in them—and they were much, much cheaper to make.

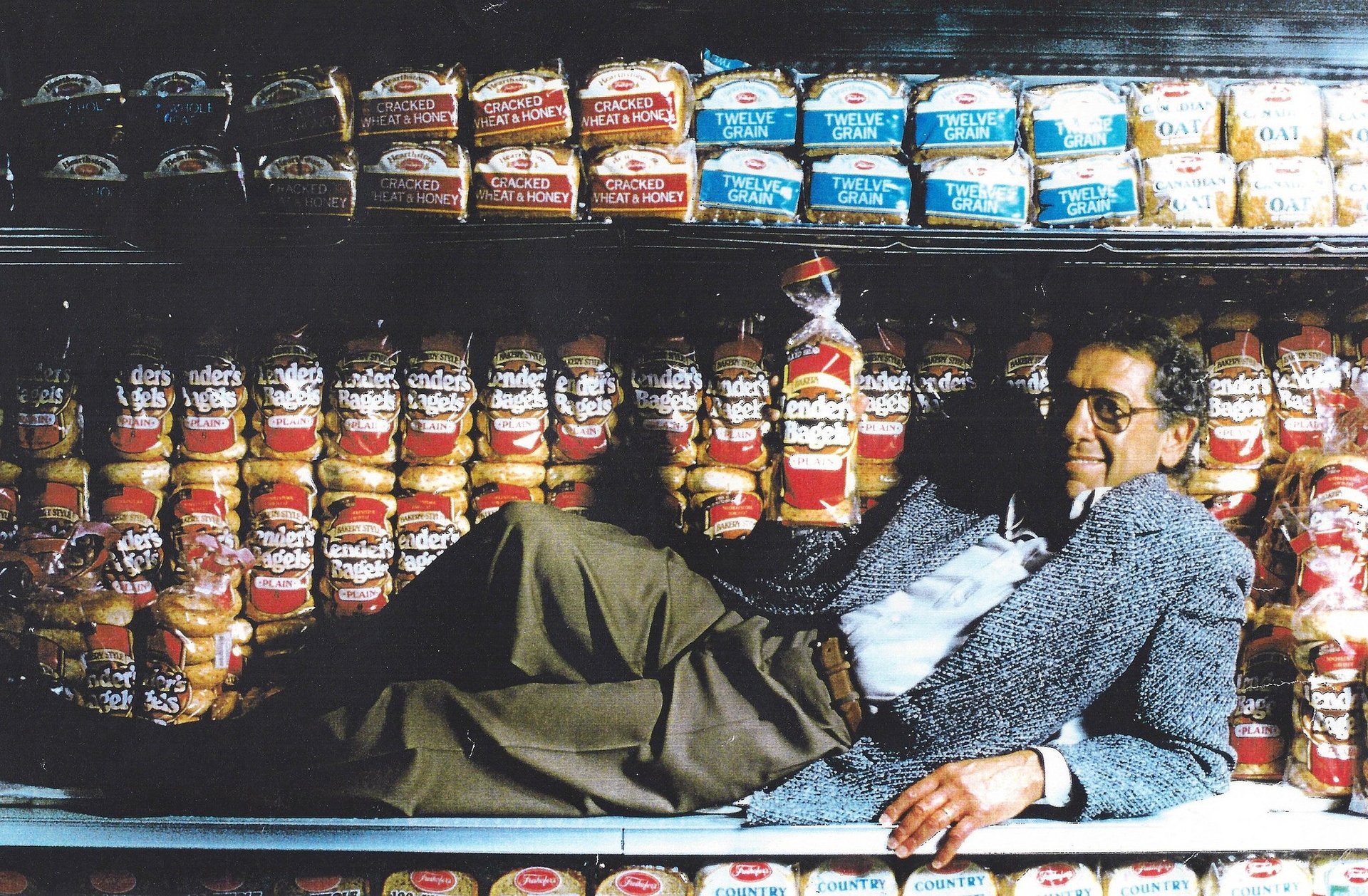

When Lender’s, a bakery in New Haven, Connecticut, acquired one of the machines to increase the number of bagels it could sell to bagel-hungry locals, it was the beginning of the end for the artisanal bagel. Americans near and far fell in love with these ultra-convenient, pre-sliced frozen bagels. They tasted of cinnamon and raisins, rather than lactic acid; you could put them in your toaster even weeks after purchase; they were small enough that they did not sit on your stomach like a rock for the rest of the day.

Crucially, as Murray Lender said in a 1969 interview, the bagel’s ethnic identity would have to be stripped back. “When most people call it a Jewish product, it hurts us,” he said. “It’s a roll, a roll with personality.” When suggesting toppings, Lender made a point of avoiding cream cheese and lox (cured salmon): “It limits them. Think of toasted bagels and jam, if you like.”

And so the bagel went mainstream, but in a form that barely resembled its original glory. By 1986, Balinska writes, total domestic sales of bagels hit the $500 million mark. Some 40% were frozen. Most of America’s bagels are still produced by these kind of machines.

The secret to New York’s high-quality bagels isn’t anything to do with the minerals in its water, as many assert. Instead, it’s the process—that people still cling onto the rituals of cooling and retarding, boiling and baking, albeit with a little help from machinery. Factory-made bagels, which tend to miss out the boiling, just can’t produce the same result.

Which is why it’s such a shame that Apple’s bagel emoji is so obviously a supermarket bagel. Emoji should be the platonic ideal of what you’re trying to express—the most elegantly crimped dumpling, the most succulent mango, the frilliest napa cabbage. Emoji like the fibrous coconut shell reveal the possibility for detail and nuance.

The bagel emoji has none of that. It’s a debasement of an iconic baked good, and an erasure of its hard-scrabble immigrant experience. We deserve better.