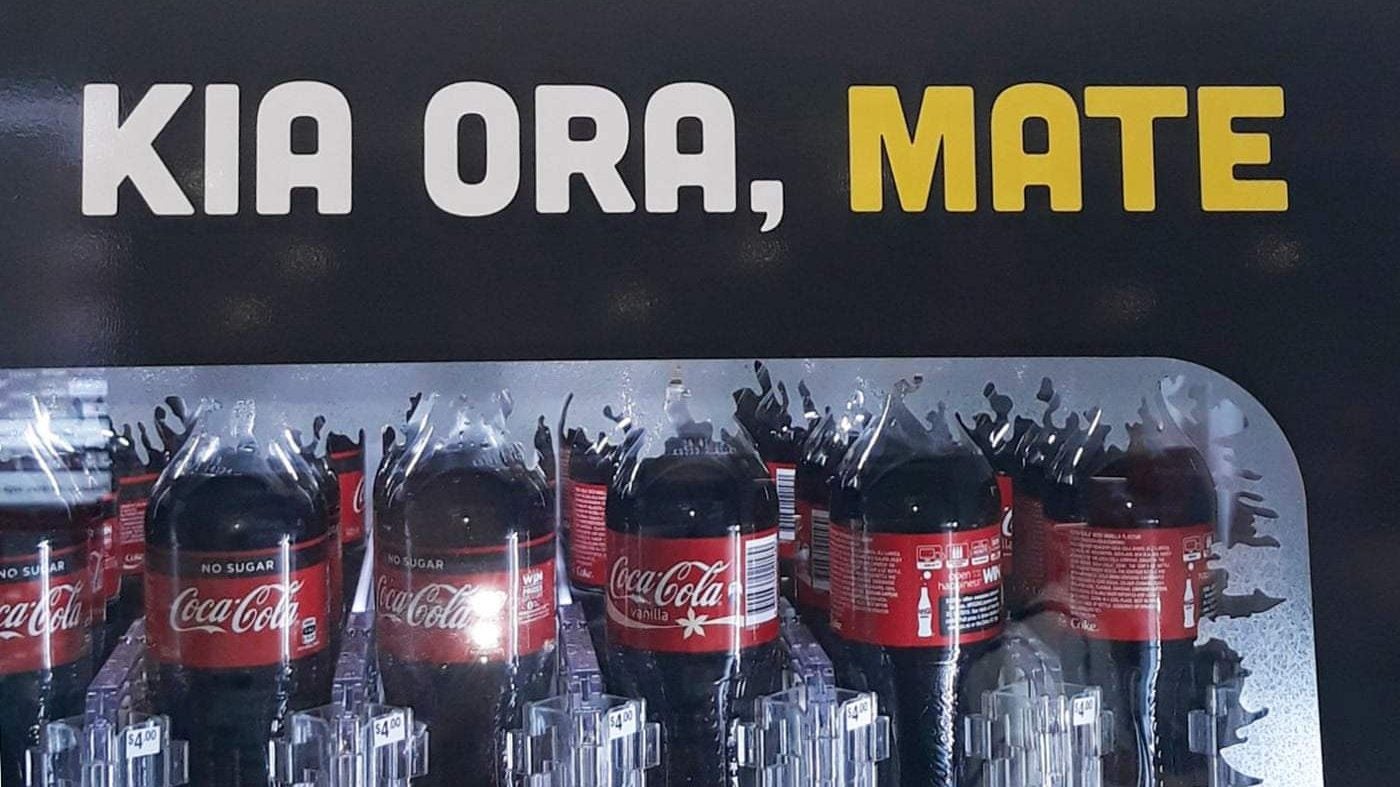

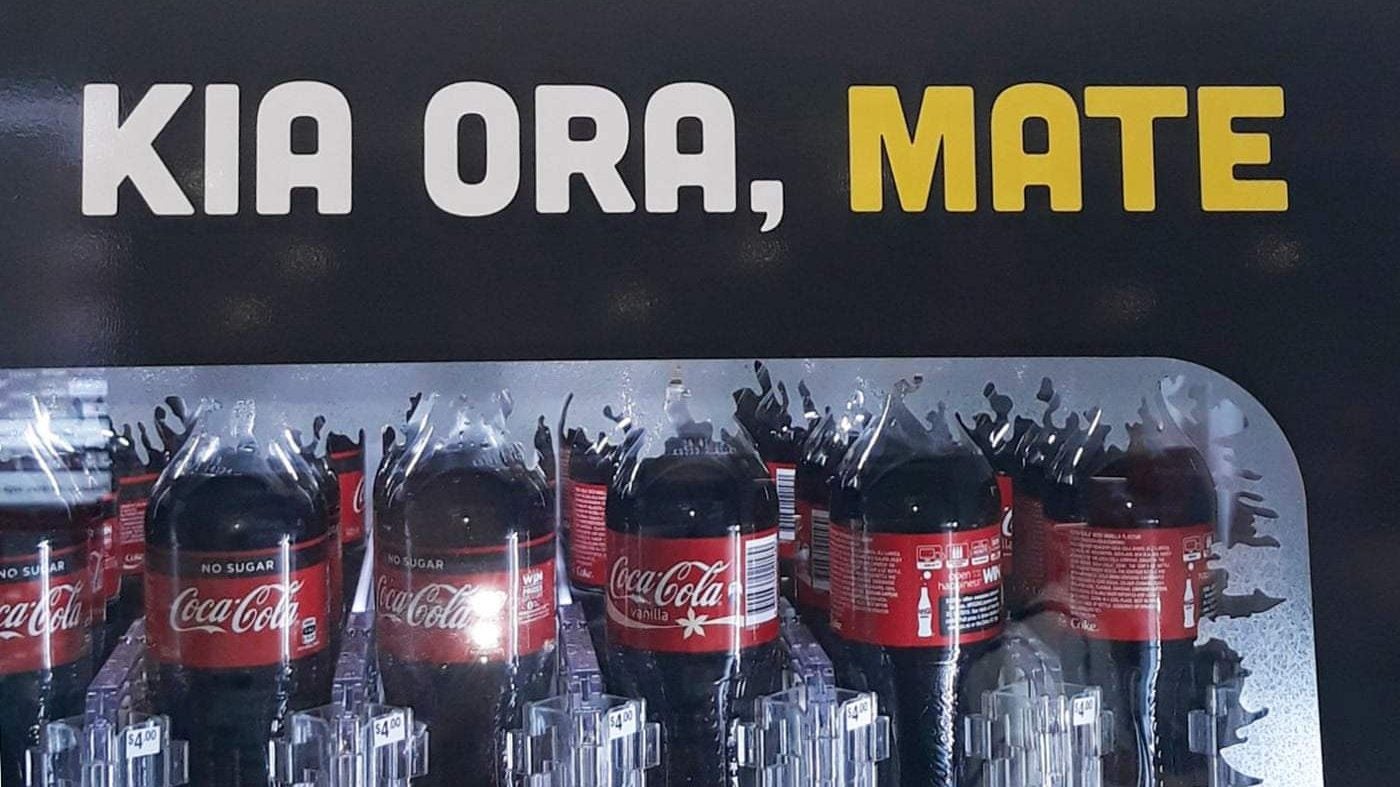

Coca-Cola accidentally greeted New Zealanders with a cheery “Hello, death”

For New Zealanders, “kia ora” is as ubiquitous as “hello,” “hi,” or even “g’day.” A Māori expression that literally means “be well,” it’s usually used as a greeting or farewell, in person, via email or on the phone.

For New Zealanders, “kia ora” is as ubiquitous as “hello,” “hi,” or even “g’day.” A Māori expression that literally means “be well,” it’s usually used as a greeting or farewell, in person, via email or on the phone.

But when Coca-Cola decided to champion “Kia ora, mate” across a New Zealand vending machine—well, they missed the mark a bit. That’s because “mate,” pronounced mah-teh, means “death” in Māori. (It can also be used to mean misfortune, problem, trouble, calamity, or disease.) All of a sudden, that culturally sensitive salutation begins to seem a little more sinister.

Jokes aside, it’s no more than an unfortunate mistake—native Māori speakers have said that it makes no grammatical sense and is something you’d never actually say. But the story does reveal the potential for big gaffes as big business engages with te reo Māori, New Zealand’s indigenous language.

All over the country, New Zealanders have been embracing the indigenous tongue with new enthusiasm. Free te reo lessons are heavily oversubscribed, teachers are working Māori words into lesson plans across subjects, and broadcasters have seized the opportunity to incorporate the language whenever they can. Corporations have taken note, too: In New Zealand itself, bilingual signs that were all but non-existent a decade ago are now everywhere from restroom doors to construction sites. Online, you can now use Google in Māori or watch the Disney hit film Moana, set on the fictional island of Motunui.

On the whole, it seems well-intentioned, rather than simply a marketing ploy, and a way to demonstrate a connection to the country and its people. “There’s an increasing sense that te reo is good for identifying your business as committed to New Zealand,” Ngahiwi Apanui, chief executive of the Māori Language Commission, told The Guardian.

But, as Māori language and culture becomes more ubiquitous, there’s the risk that businesses may bypass actually engaging with indigenous people, resulting in cultural snafus. As designer Kaan Hiini writes, “The few nods towards Māori culture to be found [are] tokenistic or cliché at best. Most involve slapping a koru [a Māori fern design] on it.” Or, you know, appearing to embrace death.

Outside of New Zealand, there’s even more potential for things to go horribly wrong. As journalist Denise Garland writes, British brewers have emblazoned the labels of their New Zealand-inspired beers with deeply insensitive images, including “a caricature of a Māori warrior riding a kiwi playing some kind of sport with a keg of beer.” Others misused sacred Māori imagery on their labels or breached customs by placing disembodied heads on their labels. When approached by Māori advocate Karaitiana Taiuru, the brewers apologized and promised to change the marketing or drop the beer from their offerings. “Unfortunately, there are no resources or guidelines to assist companies with using Māori language or culture with branding,” he told The Spinoff.

Even without official guidelines, there are many Māori people these companies, and Coca-Cola, could have approached—including Taiuru. Doing so might make the process take a little longer, but it’ll make blunders such as these far less of a risk. Kia waimarie!