An enslaved woman’s candlelit shadow is the most compelling image in the US National Portrait Gallery

The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, is home to the glorified likenesses of thousands of Americans, from US presidents and captains of industry to famous faces from the arts and sciences.

The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, is home to the glorified likenesses of thousands of Americans, from US presidents and captains of industry to famous faces from the arts and sciences.

But the museum’s most striking image was never intended as a tribute to its subject.

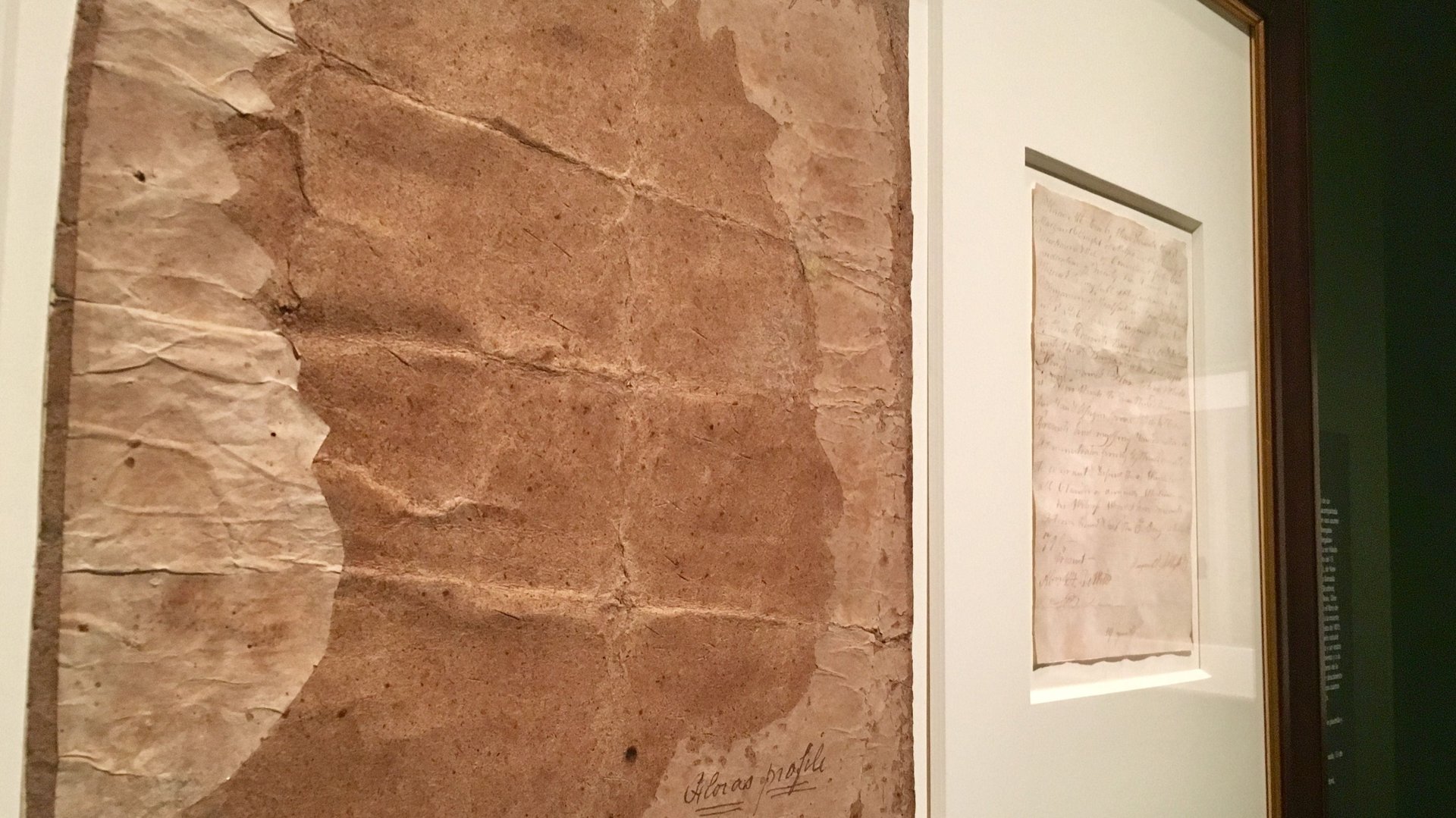

It’s a life-sized portrait done in profile, a silhouette tracing of a woman’s shadow cast against a wall by candlelight. Unlike the gilt-framed canvases hung elsewhere in this branch of the Smithsonian Institute, the 200-year-old paperboard bears the creases and crinkles of an object that has been treated without care.

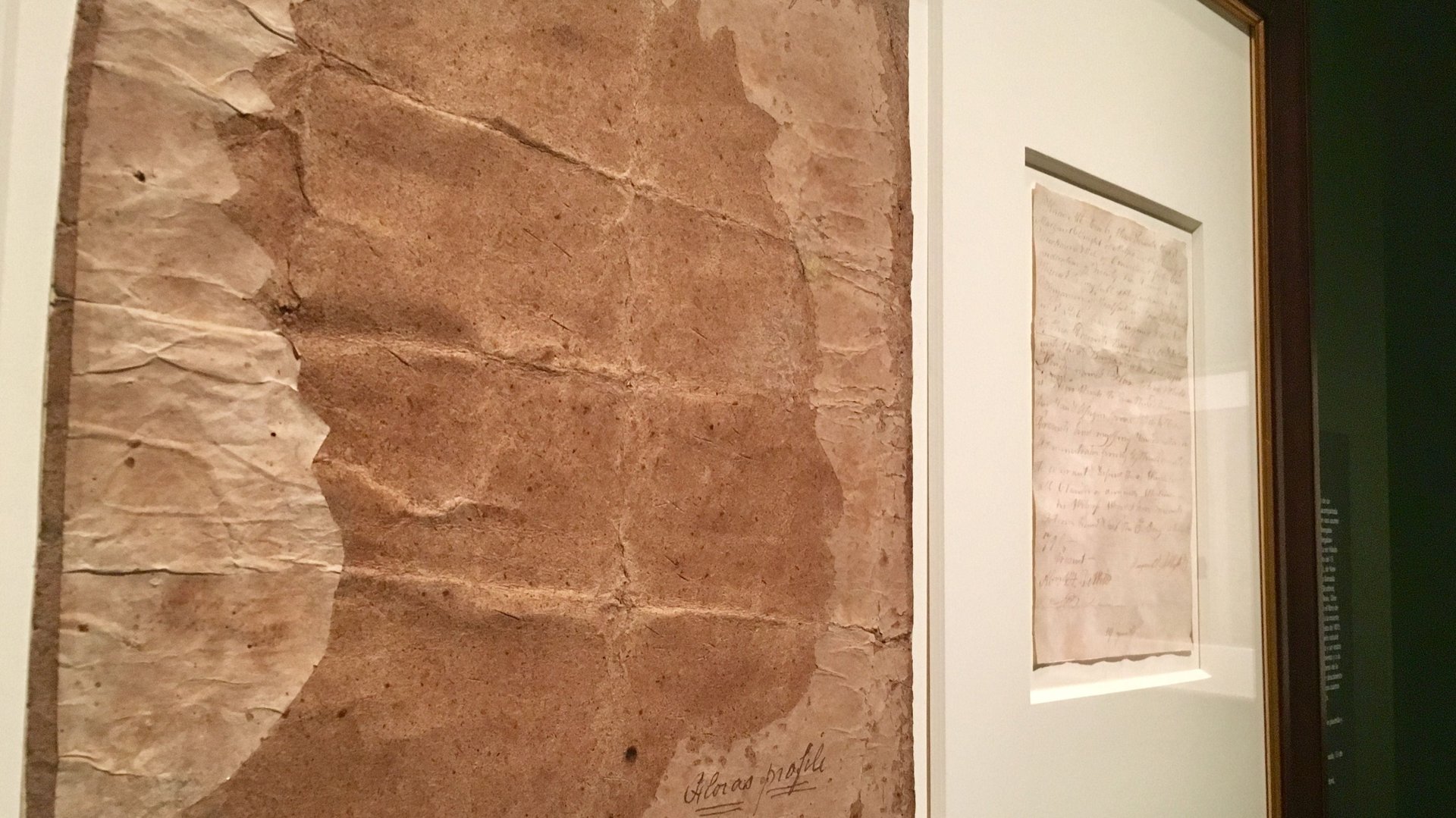

The portrait is of an enslaved woman named Flora. It is displayed in the gallery next to the handwritten bill of sale establishing the purchase for 25 pounds sterling of “a certain negro wench named Flora” on Dec. 13, 1796 by Asa Benjamin of Stratford, Connecticut, from Margaret Dwight of New Haven.

The portrait is a hollow-cut silhouette. Flora’s profile was traced upon a piece of lighter paper and then cut away, a piece of darker paperboard placed underneath to highlight what was missing. Yet from this crude outline a whole scene from a life emerges: the chin set with fear, or resignation; the candlelight flickering against a wall; the eyes looking ahead without illusion toward all that is to come.

The picture is a business document, a catalogue image for the sale and inventory of a human being. It should never have been made, yet perversely this record of Flora’s dehumanization is, centuries later, the lasting evidence of her humanity. The only other surviving record of her existence is the note in a Benjamin family ledger of the death of a woman by that name on Aug. 31, 1815.

The image is part of a fascinating exhibit at the gallery called “Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now.” The silhouette was a democratic form of portraiture. Because it required only scissors and a bit of paper, the silhouette allowed people who could never have afforded the service of a professional artist the chance to have their picture made, and to make art themselves.

The Smithsonian exhibit includes silhouettes from the 18th and 19th centuries of early Americans previously “blacked out” by history: same-sex couples, disabled people, working class individuals. It also includes work from the contemporary silhouette artist Kara Walker, whose room full of graphic images of plantation life depicts unsparingly the violence just outside the frame of Flora’s portrait.

To look at Flora’s silhouette feels in some ways uncomfortably like another violation of her personhood, as she could not have consented to the making of the image. But it also feels necessary. Her image evokes the gravity of the portraits on legal tender, a centuries-old promissory note for all that has been stolen in this country and never repaid.