An eye-opening exhibition shows how scientific breakthroughs shaped modern art

Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity changed how scientists understood the universe. It also shaped modern art.

Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity changed how scientists understood the universe. It also shaped modern art.

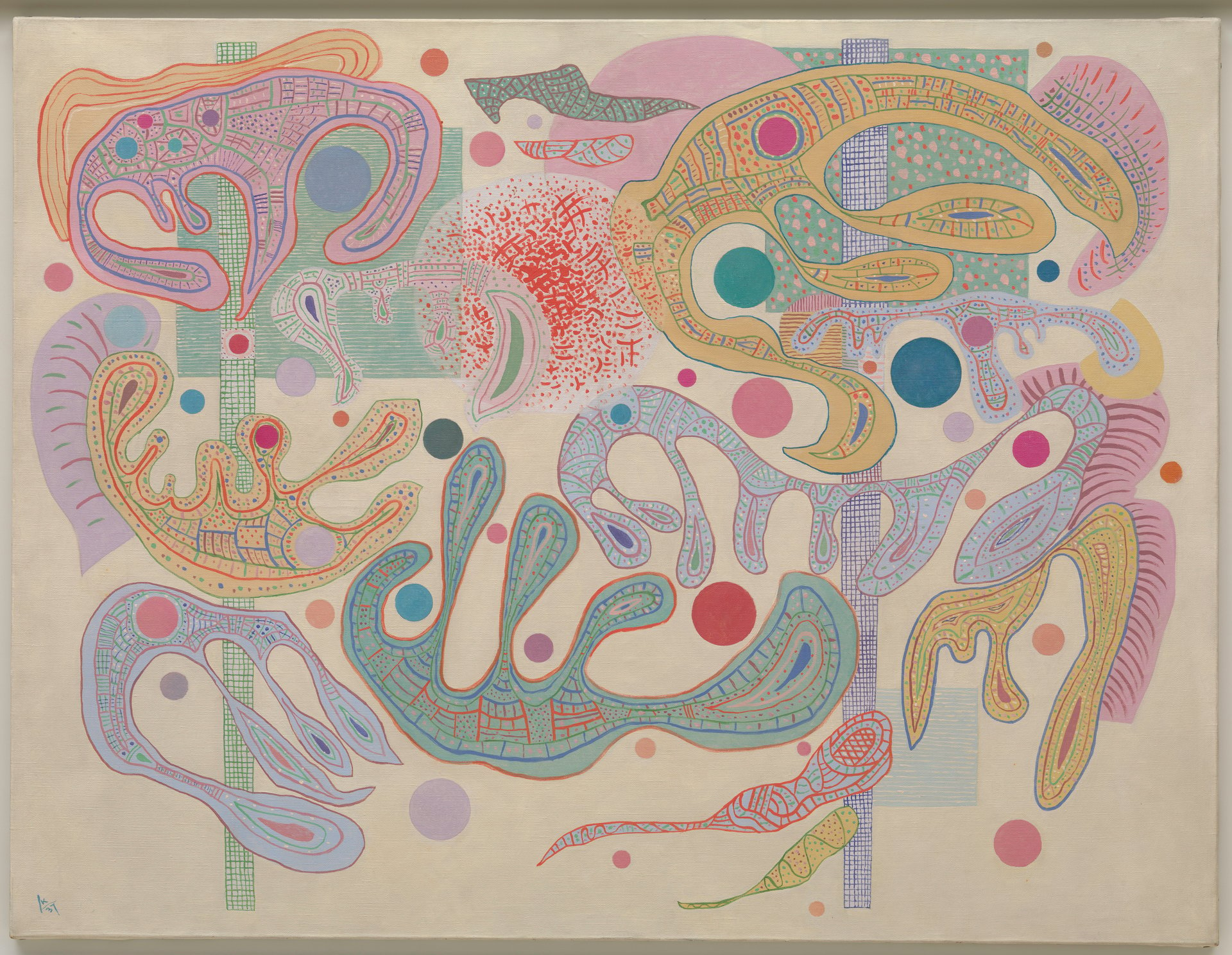

Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein, an eye-opening exhibition at the University of California, Berkeley explores how Einstein’s discovery, along with other scientific breakthroughs of the early 20th century, colored the thinking of artists such as Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, and Alexander Calder. The idea that space and time were not absolute, and that we could extend human sight with the help of new microscopes and telescopes, exploded artistic imagination, explains the exhibition’s curator, Vanja Malloy.

Dimensionism, which is currently on view at the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (and will travel to Amherst College’s Mead Art Museum in March 2019), emerged from Malloy’s dissertation about Calder’s kinetic sculptures. Her research led to Hungarian poet Charles Sirató’s Dimensionist Manifesto (pdf), which called for artists to embrace the spirit of scientific innovation and stretch beyond their usual terrain.

“We must accept—contrary to the classical conception—that Space and Time are no longer separate categories, but rather that they are related dimensions in the sense of the non-Euclidean conception, and thus all the old limits and boundaries of the arts d i s a p p e a r,” Sirató wrote. “This new ideology has elicited a veritable earthquake and subsequent landslide in the conventional artistic system.”

He implored fellow poets to present verse in graphic shapes. He urged painters to challenge the confines of their two-dimensional canvases, and he asked sculptors like Calder to create moving forms instead of stoic monuments. Penned in Paris in 1936, Sirató’s treatise was signed by leading artists such as Calder, Miro, Wassily Kandinsky, Marcel Duchamp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Bauhaus pioneer László Moholy-Nagy.

“Responding to the new science, Dimensionist art seeks to provide symbolic representations of the new conceptions of physical reality,” elaborates Malloy in the exhibition catalogue.

The exhibition of about 70 paintings, printed matter, and sculptures features early 20th-century American and European art, but contemporary examples of Dimensionist art (not included in the show) also abound, explains Malloy, who is a curator at Mead Art Museum.

“One of the goals of the Dimensionist Manifesto is the creation of ‘a cosmic space,’ where the viewer isn’t just looking at the art, but becomes fully immersed at the center of it,” she says.

In this sense, VR, AR, and participatory works such as James Turrell’s light rooms, Olafur Eliasson’s optic installations, teamLab’s luminous digital environments, and even Yayoi Kusama selfie-friendly Infinity Mirror Rooms may be categorized in the Dimensionist movement.

Dimensionism helps us see our favorite artists in a new light, says Malloy. ”Without a consideration of how scientific developments shaped many artists’ aspirations in this era and later, any study of the period will remain two-dimensional indeed.”

The choice to hold the art exhibition at in proximity to the tech hub of Silicon Valley is intentional, Malloy tells Quartz. In the same way Dimensionism challenged creative boundaries in the 1930s, she hopes that the exhibition will spur cross-disciplinary conversations among students of art and science. “Science is important, but the arts are equally important,” says Malloy. “We could all benefit from seeing that intersection more.”