The definition of “emotional labor” has changed. Don’t fight it

There’s a moment in the otherwise fairly forgettable 2006 romantic comedy The Break-Up that has stayed with me. Jennifer Aniston and Vince Vaughn, playing Brooke and Gary, have just thrown a dinner party, and they’re arguing over clean-up. She tells him that she wants him to want to do the dishes. Incredulous, he responds, “Why would I want to do dishes? Why?”

There’s a moment in the otherwise fairly forgettable 2006 romantic comedy The Break-Up that has stayed with me. Jennifer Aniston and Vince Vaughn, playing Brooke and Gary, have just thrown a dinner party, and they’re arguing over clean-up. She tells him that she wants him to want to do the dishes. Incredulous, he responds, “Why would I want to do dishes? Why?”

I remember thinking that exchange was at the heart of a huge portion of the domestic conflicts in my life, and the lives of all my coupled friends. But I couldn’t find a way to neatly describe exactly what Brooke is trying to get at when she tells Gary, “It would be nice if you did things that I asked. It would be even nicer if you did things without me having to ask you.”

The best word at the time for Brooke’s complaint was “nagging.” It wasn’t just the gendered ugliness of that word that bothered me. It was that it didn’t actually describe the specific tension of that familiar moment in a resonant way.

That term I was searching for? It now exists: “emotional labor.” And yes, I know that this definition of the phrase is different than its original academic meaning.

The new usage of “emotional labor” has gained currency as a way to describe the myriad unpaid jobs and responsibilities that people (many of them women) take on in families, offices, and communities.

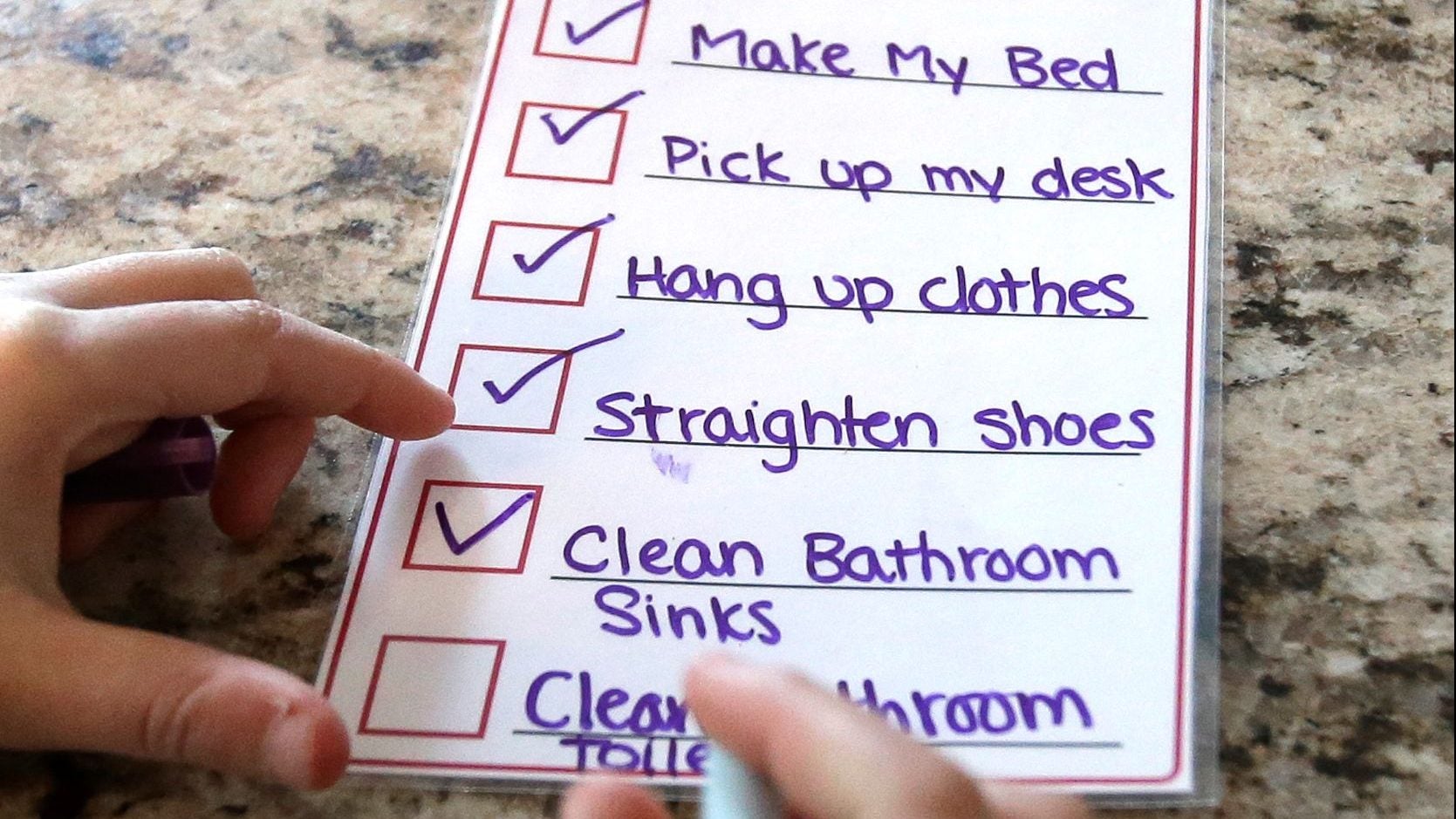

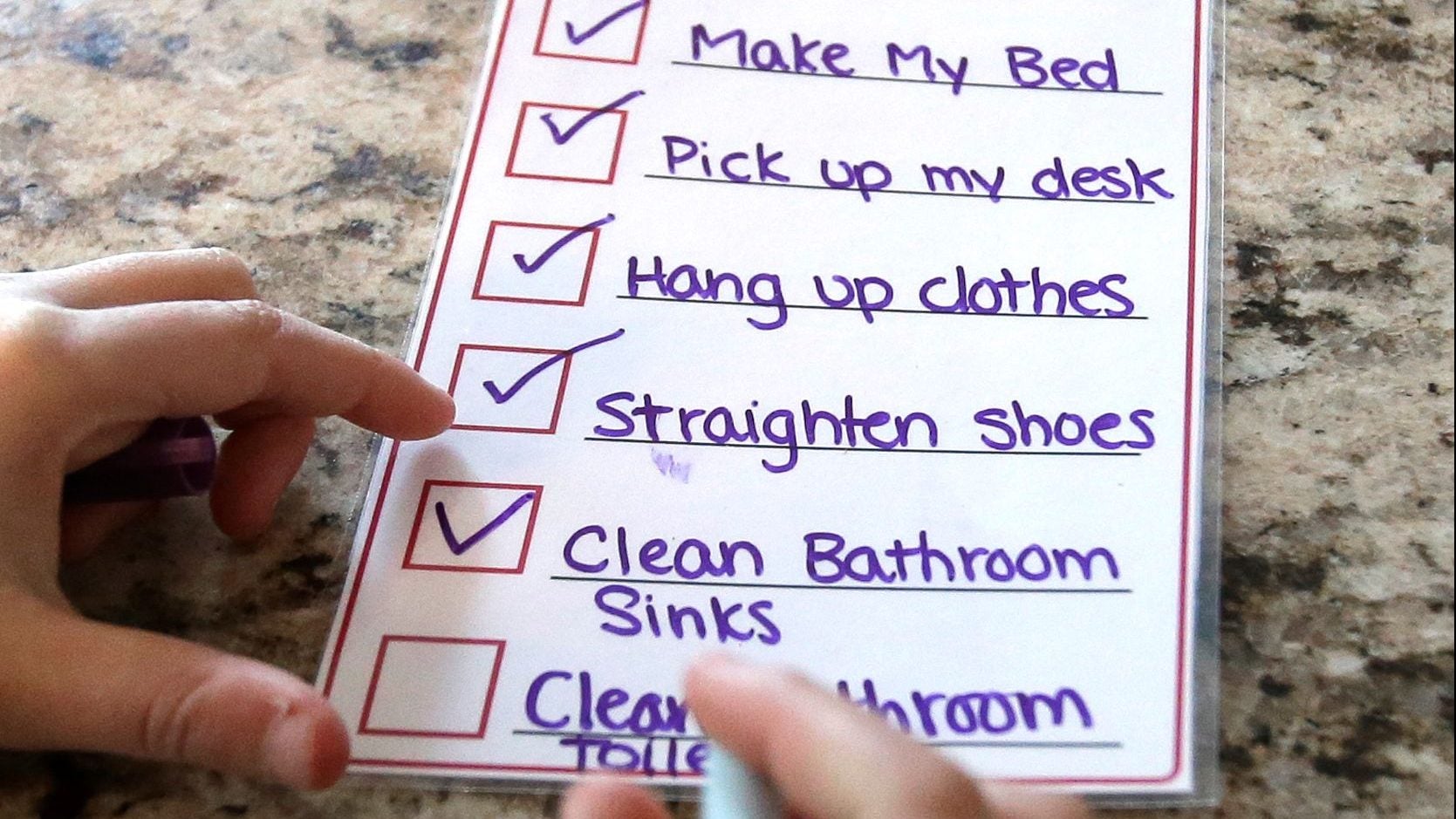

It’s a somewhat nebulous term, as Khe Hy wrote for Quartz in his “men’s guide to understanding emotional labor“: “If you poll a dozen people on their definition of emotional labor, you’ll likely get close to a dozen different answers.” In families, the term refers to the mental work required to keep a household running—all that scheduling and bill-paying and research—as well as the anxiety of being in charge of those thankless and largely invisibly tasks.

“I remember when I first heard the term emotional labor—now an essential piece of the feminist-zeitgeist vocabulary,” wrote Leah Fessler for Quartz. “Adjusting to work after college, one particularly woke friend, then age 22, began posting on social media about the unnoticed work she, and all her female colleagues, were doing in the office. Constantly smiling, making small talk, planning birthday celebrations, cleaning up after celebrations. This labor extended to her personal relationships, too—endless texting to help siblings through breakups, evaluating whether friends’ hookups were fully consensual, cleaning her roommate’s dishes.”

“Emotional labor” had a narrower meaning as it was originally conceived. In 1983, the Berkeley sociologist Arlie Hochschild coined the term in her book, The Managed Heart, to describe a component of some service industry jobs in which workers must project a different emotion than the one they are experiencing. The most often used example of this is a flight attendant tasked with maintaining an air of friendly calm, even amidst passenger complaints or turbulence (a notion that inspired an entire genre of Saturday Night Live skits). It’s a useful term, to describe a real phenomenon.

Words matter, and it’s easy to understand Hochschild’s dismay at the shifting meaning of the term she created, in the context of her work dealing specifically with paid labor. “Really, I’m horrified,” Hochschild said recently of the concept creep in an interview with The Atlantic. She described the current usage as “very blurry and over-applied,” and worried that the imprecision could blunt its power.

Here’s the thing though: Language evolves. Constantly, and without permission. “If a coinage really resonates with people and it spreads, any one person loses the ability to control how the meaning of that word changes and grows and evolves,” says Jane Solomon, a lexicographer who says that she has added “emotional labor” to her list of terms to research and potentially add to Dictionary.com, where she works.

Gemma Hartley, the author of Fed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way Forward, told me that when she was working on her book, she and her editor talked about trying to coin a new phrase, instead of using “emotional labor.” “We had talked about using ‘invisible labor’ or ‘care-based invisible labor’ to describe it, which I think would be an apt way to describe the work,” she told me over the phone. “But you know, ’emotional labor’ was already sticking.”

In this case, Hartley had played a role in helping the phrase take hold. Her viral 2017 article for Harper’s Bazaar, titled Women Aren’t Nags—We’re Just Fed Up bore the subtitle, “Emotional labor is the unpaid job men still don’t understand.” Google trends shows a steady rise in searches for the term over the past few years, with a giant spike when her article published. “I had titled it something along the lines of ‘How the mental load is dragging down equality’ and they put it up there and slapped on ‘emotional labor’ in the subhead and suddenly that was what it was, and what we were talking about,” Hartley said.

When academic terms escape into the wilderness and take on new meaning, the concepts and arguments they describe meet a broader audience. Solomon points to the idea of “intersectionality” as another modern example. Kimberlé Crenshaw, whose scholarly work introduced the idea of intersectionality to a feminist audience, used the term to mean overlapping and compounding systems of oppression—so intersectionality in her usage was a bad thing, describing a pileup of oppressions. The activists using it today have kept the core idea intact (mostly)—pointing out for instance that being a black woman doesn’t simply add misogyny to racism; the two oppressions interact.

But now, “intersectional” is often used in a positive sense as in: an intersectional approach to activism, or an intersectional outlook. It’s used to describe people working to be aware of the ways different identities overlap and intersect; and it has become shorthand for thinking outside your own experience of the world. None of this is precisely what Crenshaw meant when she coined the term, but the conversation around it is in the same spirit as her work—and has been useful. Intersectionality helped refine the conversation around the Women’s March, and its leaders, and gave the movement the language to challenge assumptions about who gets to speak on behalf of American women.

Are these modern usages in some way less precise than Hochschild or Crenshaw’s scholarship? Yes, of course they are. “Emotional labor” is being discussed by couples at kitchen tables, coming up in management training and team meetings at offices, and sparking conversations on the internet. “When you’re confined to an academic setting…there’s a little bit more control,” says Solomon. “When it’s starting to be used by everyone, that control disappears.” She pointed out that the most powerful, compelling terms and concepts hit upon something that needed a name.

And of course there’s some overlap between the original and new usages of “emotional labor”: The idea that it’s a kind of work, and a particularly taxing kind, to evoke a different emotion than the one you are actually feeling as a means to a desired end is powerful. And of course it’s there in unpaid, as well as paid, situations: Keeping your rising frustration in check, even as one child wails and another gleefully dumps juice on a stack of clean laundry, is a task. Loving the children involved doesn’t mean it’s not labor.

Hartley says that she made peace with the idea that there would be pushback on her use of “emotional labor” before publishing Fed Up. But the usage debate still frustrates her. “I’m so much more interested in talking about the idea,” she says, “and not fighting about the language.”