A photographer recreated the “sensory experience” of the Underground Railroad

The fine-art photographer and MacArthur genius Dawoud Bey has transported his audiences before, asking them to consider the hard truths and realities of history.

The fine-art photographer and MacArthur genius Dawoud Bey has transported his audiences before, asking them to consider the hard truths and realities of history.

For “The Birmingham Project,” which considered the lives stolen by hate, he created portrait diptychs. On one side of each is a child the same age as one of the four black girls killed in the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The accompanying portrait is of a Birmingham resident who is the age one of those girls would have been today, had their lives not been cut short. The pictures let the viewer imagine victims as they were, in bright light and crisp detail, alongside the unrealized potential that was never allowed.

In his newest project, “Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” on display at the Art Institute of Chicago through April 14, Bey explored historical sites that served as stops on the Underground Railroad, the network of secret roads, homes, and churches that brought escaped slaves to freedom from the pre-Civil War American south. While the Underground Railroad is believed to have helped around 100,000 slaves escape to Canada, few photographs of those who made the journey and the places they traveled exist. “The Underground Railroad is shrouded as much in myth as it is in fact,” Bey explained in an artist’s statement.

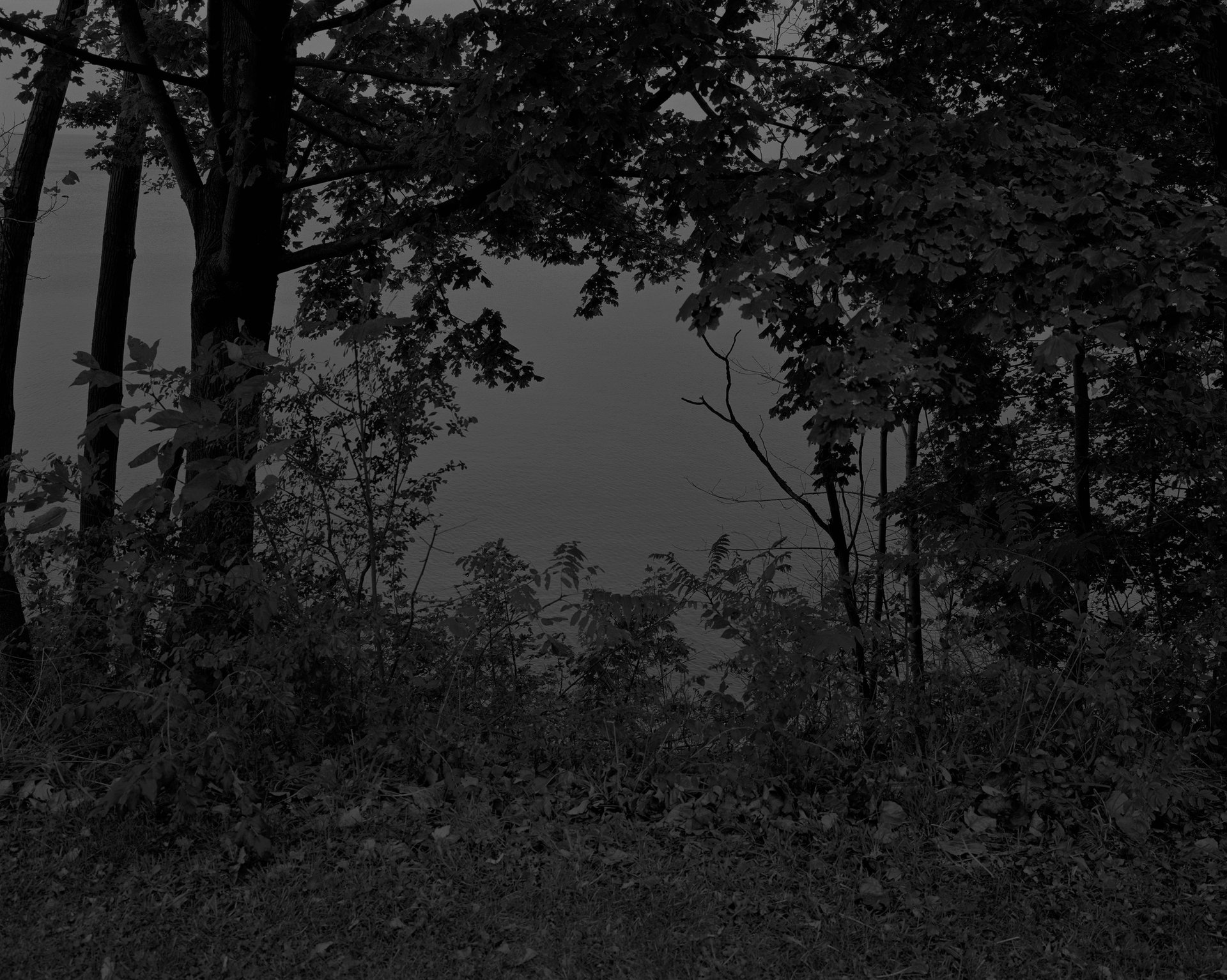

Photographed in black and white, the project’s images “seek to recreate the spatial and sensory experience of those moving furtively through the darkness.”

Bey describes the photos as landscapes, which may seem like a departure from his intimate and humane portrait work. The images still feel alive and packed with tension. The compositions and perspectives compel the viewer to squint through a thicket of branches, peek from behind a tree, or gaze into a vast expanse of water. The images transport a viewer into the point of view of an escaped slave.

An open field or the shore of a lake can seem like dangerous obstacles. Yet an unfamiliar home can be a potential refuge. Bey significantly darkened the images to further illustrate his point. Instead of the high-contrast black-and-white images he has has produced in previous work, these photos are printed using a dark palate of muddy grays. The loss of clarity evokes twilight creeping in, a growing unfamiliarity with surroundings.

“I want that history to resonate for the viewer and bring them visually into the experience of what it might have felt like as those fugitive black bodies negotiated that unfamiliar terrain in pursuit of freedom,” Bey said over email.

Here is a look at a selection of Bey’s images: