Before we knew better: Silence of the Lambs is a win for women—but fails LGBTQ culture

In this mini-series, we return to movies and TV we’ve loved to see how they depict gender. Does it hold up in 2019? Warning: contains spoilers.

In this mini-series, we return to movies and TV we’ve loved to see how they depict gender. Does it hold up in 2019? Warning: contains spoilers.

When did it come out? 1991

How does it hold up? Profoundly mixed bag

There’s a moment in the electrifying first meeting between Clarice Starling, the FBI agent-in-training, and Hannibal Lecter, the psychopath, where the gloves come off and he drops the pretense of carefully polished manners and reads her for filth. “You know what you look like to me, with your good bag and your cheap shoes?” he says. “You look like a rube. A well scrubbed, hustling rube.”

He could be offering his assessment of the film itself, at least where gender is concerned: It’s a good bag, well-made and classically styled. But this nuanced depiction of women only calls attention to the tawdry cheapness with which LGBTQ culture is drawn.

Nearly 30 years later, Silence of the Lambs paints a portrait of sexism and misogyny that still feels carefully nuanced and intricately layered. Starling is not a rah-rah, you-go-girl token female lead. It’s crucial, not incidental, to the film that she is a complex human being. Jodie Foster who plays Starling, had become known in Hollywood for her ambitious, feminist work. In 1989 she won an Oscar for her role in The Accused, in which she plays an unsympathetic rape victim who exposes the deep misogyny of the criminal justice system. Silence of the Lambs fails gay culture, though, which is depicted as a seedy, horrific underworld, stalked by literal monsters. You couldn’t design a more transphobic bad guy than the serial killer Starling spends the movie in search of.

The basic plot is a grislier-than-average whodunnit—Starling, an ambitious FBI-agent in training is recruited to ask one serial killer, Lecter, also a former psychologist and infamous cannibal, about another. She’s looking for his insight into Buffalo Bill, a killer who abducts, murders, and then skins his female victims. Bill, as Starling discovers, wants to make himself a suit out of real women. Starling and Lecter strike up a surprisingly intimate relationship; she catches the killer, and rescues his latest victim; Lecter, however, escapes.

Foster brings a ferocious intelligence to the role and offers a masterclass in workplace sexism. She plays both the quotidian and the extraordinary discomforts of being the only woman in the room, and sometimes the building: She’s sexualized, condescended to, used as a token, and a pawn, and yet, even when her body trembles, her gaze never wavers. Male students turn to watch her run by in baggy sweats and a turtleneck; she faces Lecter’s appraising stare; Buffalo Bill hunts her using night vision goggles. Starling returns their gaze with her piercing blue stare.

What’s rare about the movie is its self awareness. Starling reacts to and sometimes course corrects moments of discomfort. In one scene she takes a moth pupae, found in the throat of one of Buffalo Bill’s victims, to a team of entomologists so nerdy that they wouldn’t seem out of place working with The X-Files‘ Lone Gunmen. As they carefully dissect the pupae, one pauses to flirt with her. It’s a slightly creepy, mostly charming moment that goes nowhere, but a look crosses Agent Starling’s face, that mixes genuine bemusement with a reaction something like, “Jesus, even you guys?”

In another scene her boss Jack Crawford, played by Scott Glenn, implies that it would be inappropriate to discuss the details of a sex crime in mixed company, taking a local sherif aside and leaving Starling in a room full of smirking deputies. “When I told that sheriff we shouldn’t talk in front of woman, that really burned you didn’t it?” he asks her later in a slightly incredulous tone. “It matters, Mr. Crawford,” she replies. “Cops look to you to see how to act. It matters.”

Starling breaks the case because of her ability to see women, not as objects or victims, but as full human beings. She finds Buffalo Bill because she’s able to see the small town life of his first victim in the round—locating secret nude Polaroids hidden in a music box and talking to her best friend frankly.

This is not to say that Silence of the Lambs is feminist. Its treatment of body size is appalling. The film describes the murdered women in a variety of ways that strip their bodies of dignity. There’s a lot of ugliness toward women in this movie—one of Lecter’s fellow inmates first tells Starling, “I can smell your cunt,” then throws semen in her face.

The nuance that Foster brings to Agent Starling makes the inhuman portrayal of transgender people all the more stunning: They’re simply monsters.

Buffalo Bill stocks his basement lair full of sewing forms and mannequins, playing dress-up, and stroking his poodle named Precious. At one point he retrieves an insanely huge gun out from under a quilt patterned with cheerful, yellow swastikas. He’s terrifyingly powerful, yet mincingly feminized. He’s the specter of the scary man in a wig—made from an actual scalp—that every trans-focused bathroom ban attempts to conjure. Silence of the Lambs makes no attempt to understand transpeople, or the wider LGBTQ community, painting a picture of a grimly marginal life of dangerous sex and macabre interior design.

Silence of the Lambs, oddly, is a blueprint for the uglier elements of what’s become known as the trans-exclusionary radical feminist movement, which takes an absolutist stance on what a defines a female body and a female experience of the world. There’s a zero-sum mindset in both, in which transwomen are accused of somehow erasing the experiences of other women—just as Buffalo Bill has to murder women to fully inhabit the identity he wants.

In 1991 and 1992, as Silence of the Lambs emerged as a strong Oscar contender, there was outcry from the gay community about the depiction of Buffalo Bill (though at the time the criticism was more broadly about homophobia). Jonathan Demme responded that the character was not supposed to be gay or trans, but rather someone so profoundly damaged that he was seeking transformation in any way possible. At a moment when gay identity was still so closely associated with the very real contagion of the AIDS crisis in the minds of much of the public, this distinction was drowned out by yet another way to pathologize queer identity.

In The New York Times, Vincent Canby predicted that the film, “Could well be the first big hit of the year,” after praising Foster’s performance by way of calling her “exceptionally pretty.” In Rolling Stone, Peter Travers put his finger on something more significant about the film, writing, “Foster’s Clarice Starling and Smith’s Catherine Martin represent something unique in slasher movies: women who won’t play victim.”

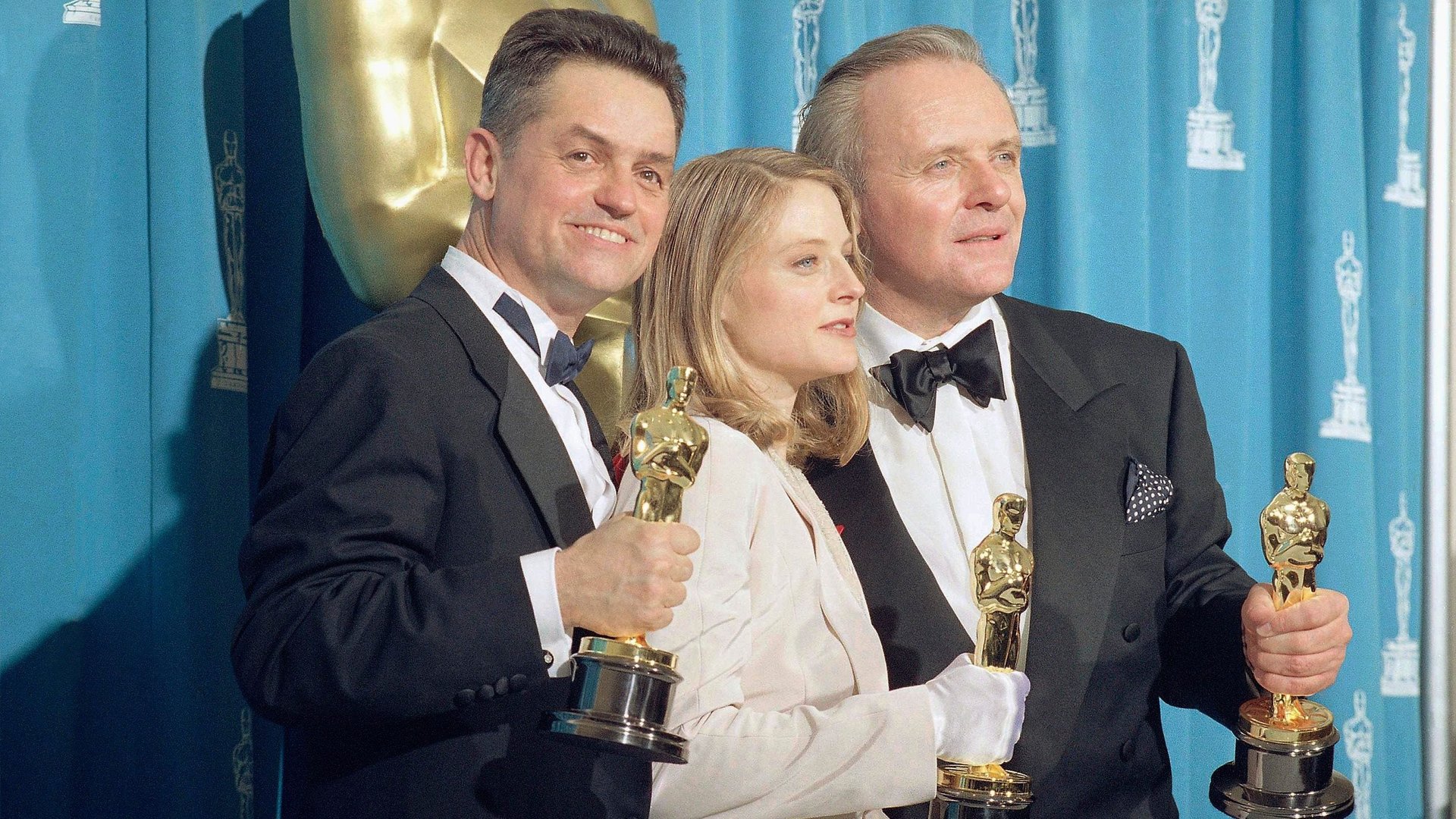

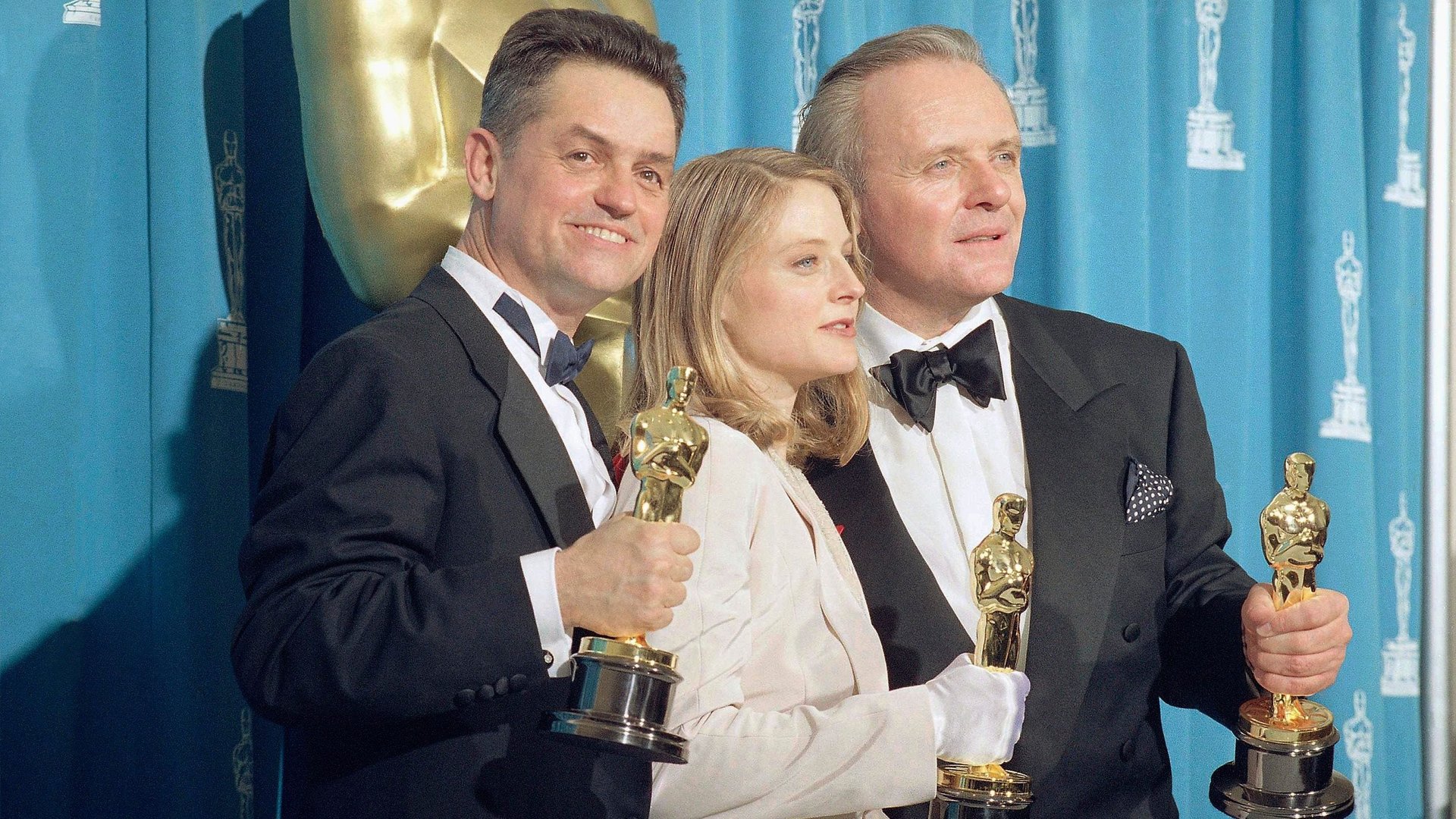

Silence of the Lambs swept the Academy Awards in 1992, winning Best Picture; Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins, who played Starling and Lecter, also won individual Oscars for their performances, and Jonathan Demme took best director.

Its success fits into a long, problematic, pop culture obsession with serial killers, one that’s more interested in their pathology than the suffering of their victims. Mandy Patinkin, one of the original stars of the TV show Criminal Minds, which is based on the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit (which Jack Crawford leads in the movie) abruptly left the show after just two seasons. “The biggest public mistake I ever made was that I chose to do Criminal Minds in the first place,” he told New York Magazine. “I thought it was something very different. I never thought they were going to kill and rape all these women every night, every day, week after week, year after year. It was very destructive to my soul and my personality.”

At the end of Silence of the Lambs, Hannibal Lecter strolls off into the sunset in some undisclosed tropical place, clad in an impeccable white linen suit. It does not feel like we’ve seen the last of him; he returns in two sequels, Hannibal and Hannibal Rising.

Starling’s legacy is more complicated. On television, cop shows tend to depict squad rooms where gender parity is the norm. Get the women talking though, and the story remains the same—on the CBS show FBI, sexism, at Quantico and in the bureau, is a major theme for several female agents. Starling’s most direct pop culture descendent has to be Olivia Benson, the intrepid detective turned lieutenant from Law & Order: SVU. The show, now in its 20th season, has had a chance to reconsider the way it depicts specific communities over the course of its long run. It too, started out serial-killer obsessed, with an ugly tendency to use transgender women as a punchline. In recent seasons though, it has evolved to focus on hate crimes, sexual harassment, and the power dynamics of sexual assault.

And Criminal Minds? The show that glorified serial killers so much that Mandy Patinkin quit? That team is now half female, and led by a woman. The real heart of the show is a former hacker with a penchant for wild floral prints and unicorns, who would have located Buffalo Bill far more quickly than Starling ever could, simply by searching the dark web for digital breadcrumbs.

This story is part of How We’ll Win in 2019, a year-long exploration of workplace gender equality. Read more stories here.