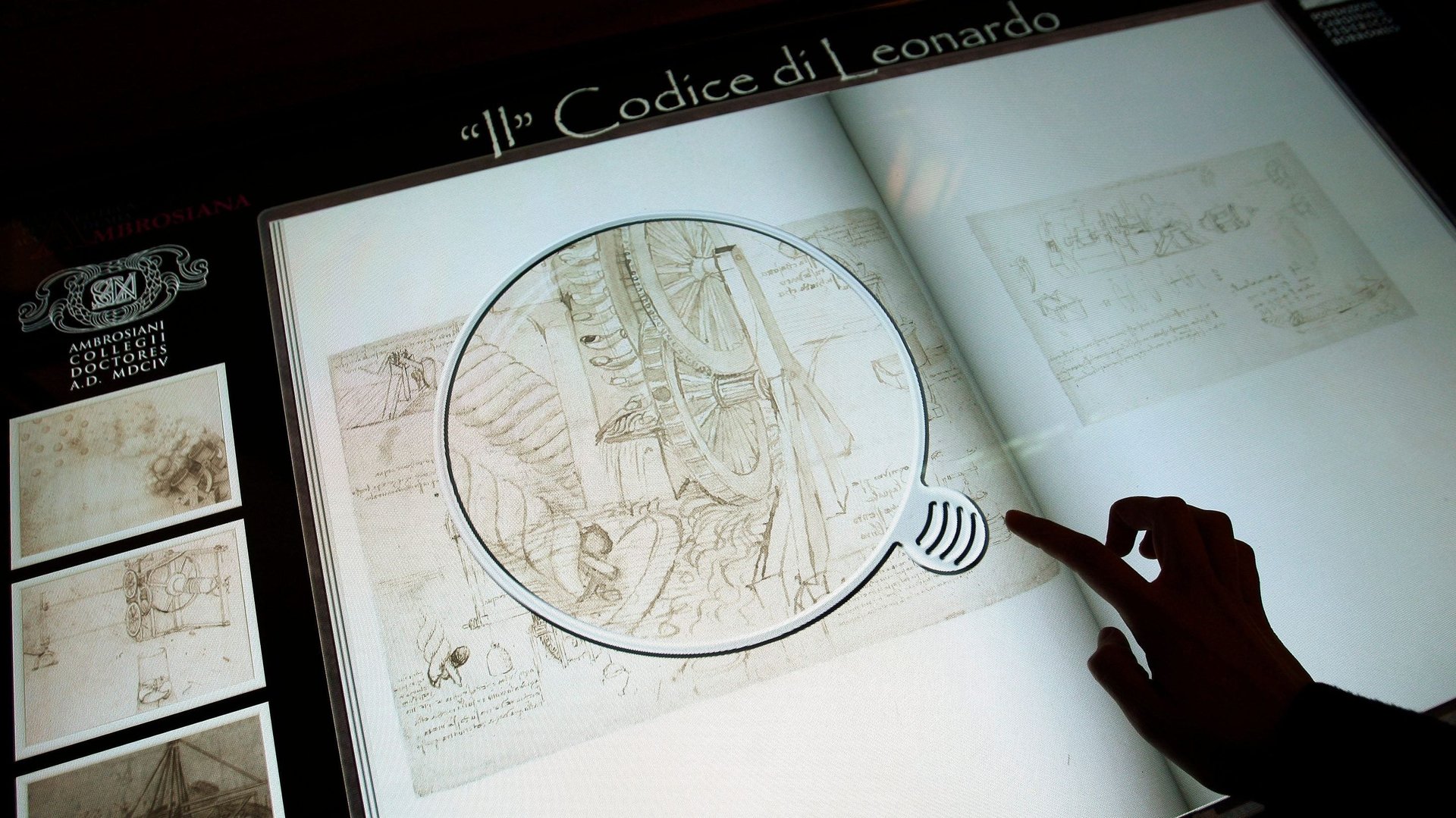

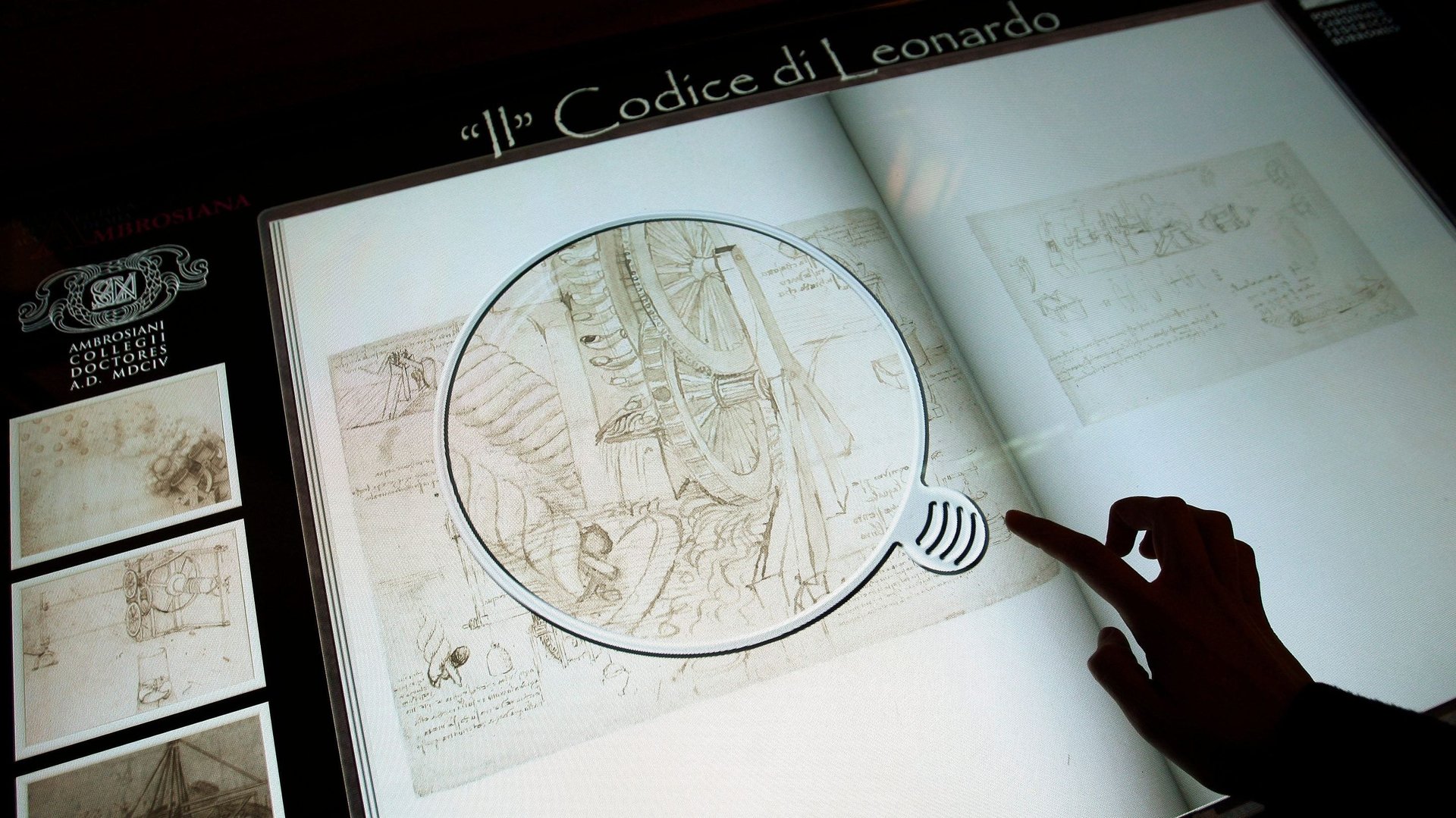

Leonardo da Vinci showed how art can advance scientific progress

Leonardo da Vinci’s remarkable capacity for careful observation made him an astonishing artist and a brilliant scientist. He was able to compare the speed of a bird’s wing movement downwards and upwards. He noticed the differences between arteries carrying blood from the heart and the veins bringing the blood back, so as to draw accurate models of the human circulatory system. His portrait paintings were groundbreaking because Leonardo was the first to show accurate musculature in the face and neck.

Leonardo da Vinci’s remarkable capacity for careful observation made him an astonishing artist and a brilliant scientist. He was able to compare the speed of a bird’s wing movement downwards and upwards. He noticed the differences between arteries carrying blood from the heart and the veins bringing the blood back, so as to draw accurate models of the human circulatory system. His portrait paintings were groundbreaking because Leonardo was the first to show accurate musculature in the face and neck.

Beyond applying his artist’s perceptual capabilities to scientific topics, Leonardo took on artistic and engineering challenges that built on his knowledge of geology, weather, hydrology, botany, and much more. Leonardo’s natural state of mind was to integrate art, design, engineering, and science. That integrative spirit inspired other legendary artist-scientists, such as John James Audubon, Louis Pasteur, Ada Lovelace and Buckminster Fuller.

However, in the 20th century, scholars began focusing on specialties, fragmenting academic disciplines. More recently, though, researchers are rethinking that approach, drawing attention to the value of bridging disciplines to inspire discovery and innovation.

At a 2018 meeting that I organized for the National Academy of Sciences, a diverse group of academics talked about examples of how scholars of art, design, engineering, and science can work together for mutual benefit, as Leonardo found in his day. There are several good starting points for those who want to understand, teach, and benefit from an integrative approach.

Arts training helps scientists excel

Leonardo’s celebrated perceptual skills made him a compelling artist. They also improved his science, enabling him to draw accurate representations of water swirling around objects, and the movements of clouds. This tradition is apparent in Audubon’s bird paintings and the anthropology drawings of Mary Leakey.

Medical professionals may also find that training in the visual arts can help them in their jobs. For instance, after dermatologists were asked to study museum paintings they had improved their capacity to spot and describe features in skin lesions. Art training also improves clinician skills such as patient examination and reading medical images.

Similarly, musically trained doctors are better at hearing the nuances in heartbeats when they use their stethoscopes. Nursing students who got musical training were able to more accurately identify sounds from patients’ stomachs, hearts, and lungs.

Louis Pasteur’s training in making portraits probably helped him understand chirality, the mechanism by which how molecules can take left-handed and right-handed forms.

Sociologist of science Robert Root-Bernstein, who has long researched the sources of extreme success in science, studied the avocations of Nobel Prize winners. He found them to be polymaths who were far more proficient in producing art, sculpture, music, literature, poetry, theater, and other creative activities than other prominent researchers or the general public.

Artistic innovation challenges scientists

Some creative ideas can’t be executed without science. For instance, engineer Karlheinz Brandenburg wanted to enable audio recordings to be digitally recorded in a compact way that would allow songs to be transmitted over slow communications lines. He developed the hugely successful mp3 audio format, whose compressed data formats enabled the digital music revolution, while at the same time revolutionizing computing algorithms research.

Artist Lillian Schwartz, who carefully studied Leonardo’s work, was a participant in the 1960s group Experiments in Art and Technology. While at Bell Labs, she worked with computer graphics innovator Ken Knowlton to develop computer animation techniques that laid the foundation for Hollywood special effects and the computer games industry.

Play expands engineers’ thinking

Training in making art, design, and craft work can help scientists and engineers better in their work. Flourishing design schools, like the Rhode Island School of Design, Savannah College of Design, or Canada’s OCAD University, as well as design departments at many universities, are demonstrating that they teach skills that accelerate work in many fields. Their students learn important lessons from the experience of wrestling with design problems, trying multiple approaches with sketches and drafts, and getting feedback during studio reviews. These lessons appear to improve performance in science and engineering research.

The growing movement known as “practice-based research” in the art and design community generates new knowledge, which can lay the foundation for further discovery and invention. A favored technique for combining art/design with science/engineering is to create long-term collaborations so as to get past the early stages of learning new language and methods. A study of 118 such collaborations, supported by the Wellcome Trust, demonstrated ample benefits.

Art can inspire scholars in other disciplines

While it is difficult to track, it seems reasonable to assume some artistic productions like paintings or sculpture or performances of music or theater triggered a scientist or engineer to make a connection or think in a fresh way about a problem that they are working on. Einstein claimed that music underpinned the insights that led to his theory of general relativity.

Seeing an Escher print of fish arranged in a grid stimulated NYU chemist Nadrian Seeman to produce the first DNA-based nanotechnologies. He writes that art can “generate or help illustrate structural ideas—possibly new structural ideas—about DNA.”

Superstar engineer Buckminster Fuller’s ideas of tensegrity were put to work in Kenneth Snelson’s innovative constructions, which combined steel cables and aluminum cylinders, creating large visually engaging public sculptures. These sculptures also helped molecular biologists understand the structure of large molecules.

Other stories describe how a Miro painting, a Calder mobile, or a Stravinsky symphony inspired 20th-century researchers. How do the works of painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, space artist Trevor Paglen, or dance choreographer Liz Lerman inspire 21st-century researchers?

Inspiring examples from the Science, Engineering, Art, and Design website tell the stories of how collaborations work. High school and university instructors who give their students the experience of working in team projects will better prepare them for a life of successful creative partnerships. Another indication of the growing appreciation of integrative ideas is that design thinking has gained recognition for its benefits to business in product and service development. For the long term, I propose the development of a U.S. National Academy of Design, to join the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. This won’t be easy, but it would restore prominence to the power of integrative thinking that Leonardo still exemplifies.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.