Jumpsuits have finally conquered the boardroom

Executive coach Dawn Metcalfe’s go-to stage outfit isn’t a dress, or a suit, or trousers, or even a skirt. Instead, it’s all of them at once. The garment is somewhere between rust and maroon in color, with t-shirt-length sleeves and a faux-skirt over three-quarter length trousers. Its divided hems curve like petals over Metcalfe’s legs.

Executive coach Dawn Metcalfe’s go-to stage outfit isn’t a dress, or a suit, or trousers, or even a skirt. Instead, it’s all of them at once. The garment is somewhere between rust and maroon in color, with t-shirt-length sleeves and a faux-skirt over three-quarter length trousers. Its divided hems curve like petals over Metcalfe’s legs.

It’s a jumpsuit, striking and chic—and she loves it. “It covers me, but is also a bit unusual,” she told Quartz.

But there’s one key drawback: it’s literally impossible to zip and button by herself. And that means she can’t use the bathroom without help. When she travels to speak at events, Metcalfe says, “either I have a colleague with me, or I ask someone. I live in the United Arab Emirates, so mostly there are attendants in the bathroom, too.” (Happily, it inevitably leads to a lovely conversation, she says.)

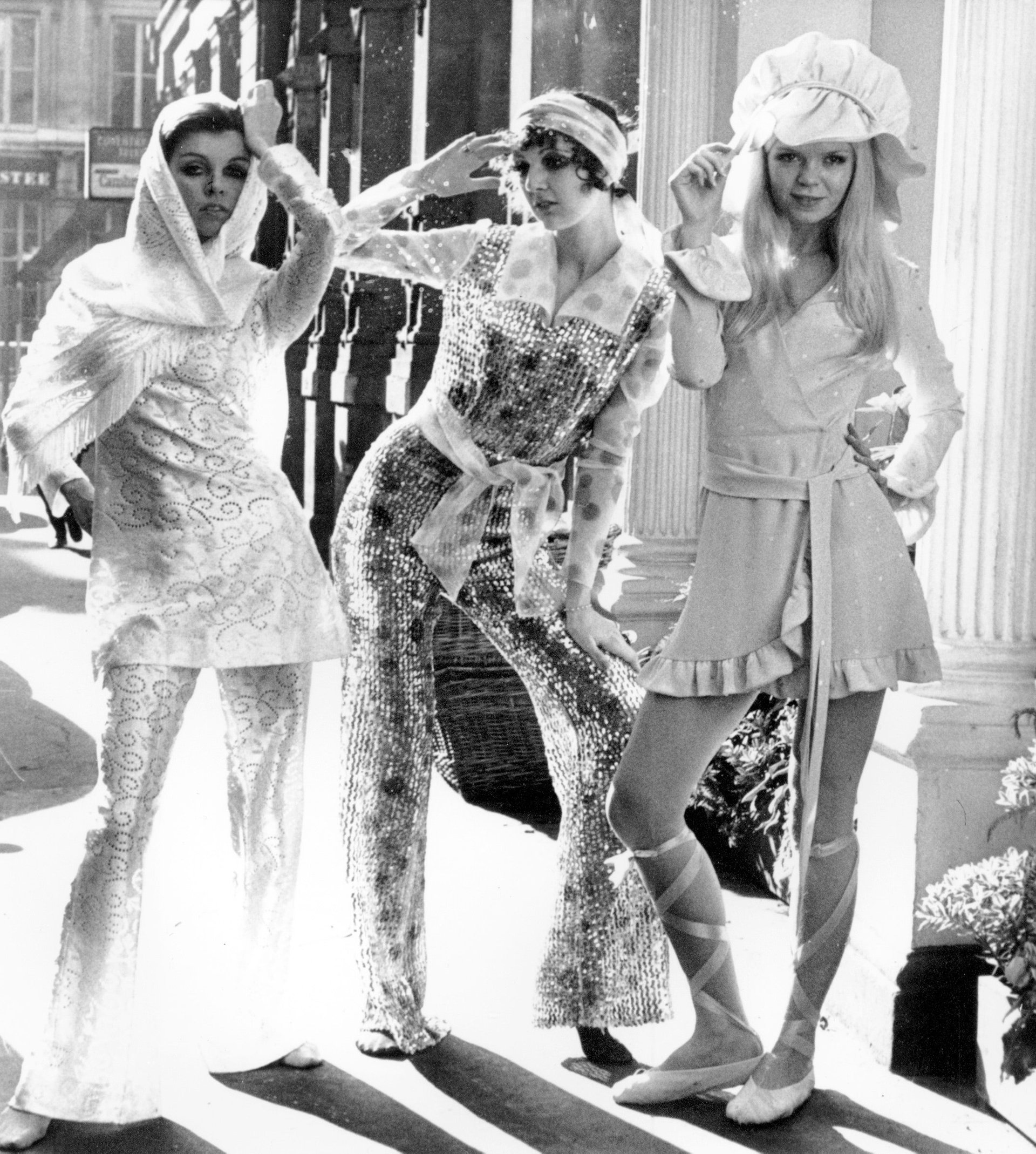

This is a well-known downside of wearing a jumpsuit, and one reason why, historically, they’ve failed to make it into the mainstream. Instead, for nigh on a century, jumpsuits have been billed as the clothing of the future, writes the clothing historian Cassandra Gero in her thesis on jumpsuits, appropriate for some unspecified tomorrow. They have variously been the domain of “blue collar workers, lounging ladies, military pilots, sky-divers, athletes, artists, utopian thinkers, glam-rockers, space-age youths, modern dancers, disco dancers, fetish enthusiasts, Star Trek fans, and more.”

Now, they’re hitting the boardroom. More than a century after French fashion designer Paul Poiret first debuted the loungewear “pantaloon gown,” jumpsuits are striding into perhaps the most conservative corner of women’s fashion: white-collar corporate workwear.

At the high-powered Milken Institute conference in Los Angeles last month, a not-insignificant number of female executives interpreted the vague “business attire” dress code as sleek, single-color jumpsuits in shades of maraschino cherry red or sky blue. They could have drawn inspiration from plenty of other high-profile examples: Ivanka Trump wore bottle green at the 2017 G20 summit meeting in Hamburg, Germany, while her stepmother, Melania, favors sleeveless black versions for official events.

I spoke to dozens of women who love to wear jumpsuits to work, all of whom were enthusiastic about them in a way that might seem perverse about any other item of clothing. They thought they were fun, sleek, stylish, and modest without the perceived unprofessional frump-factor of a maxi dress. They loved that they had pockets. They found them flattering, even as they regretted a lack of options for people who are not tall, slim, and relatively gamine of figure. And although they acknowledged jumpsuits’ certain practical limitations, they found them overwhelmingly empowering to wear, much like high heels. That’s despite the fact that the corporate jumpsuit, and its more casual all-in-one cousins, are neither as comfortable nor as convenient as they appear.

One garment, many uses

Jumpsuits have long had an association with revolution and newness. In 1911, French designer Poiret produced vivid illustrations of women in jumpsuit-like attire doing leisurely activities like gardening, playing tennis, and taking time to sniff the flowers, with the caption ‘Celles de Demain’—tomorrow’s fashions. Less than a decade later, the Futurist artist Ernesto Michahelles, known as Thayaht, designed and promoted his TuTa as “the most innovative, futuristic garment ever produced in the history of Italian fashion.” Next, in the 1920s, Constructivist artist-engineers in the newly-created Soviet Union looked to the jumpsuit as a key example of the anti-fashion of the glorious future. In February 1939, Vogue magazine asked nine designers for their spin on the clothing of the future. Two suggested jumpsuits.

In all these early incarnations, jumpsuits were proposed as an androgynous option, appropriate for a forthcoming genderless era. But as time went on, they remained more of interest to women than men—whether due to a male disinterest in an item of clothing that actively limits how easily one can navigate the world, or a preference for a bit more room around the crotch.

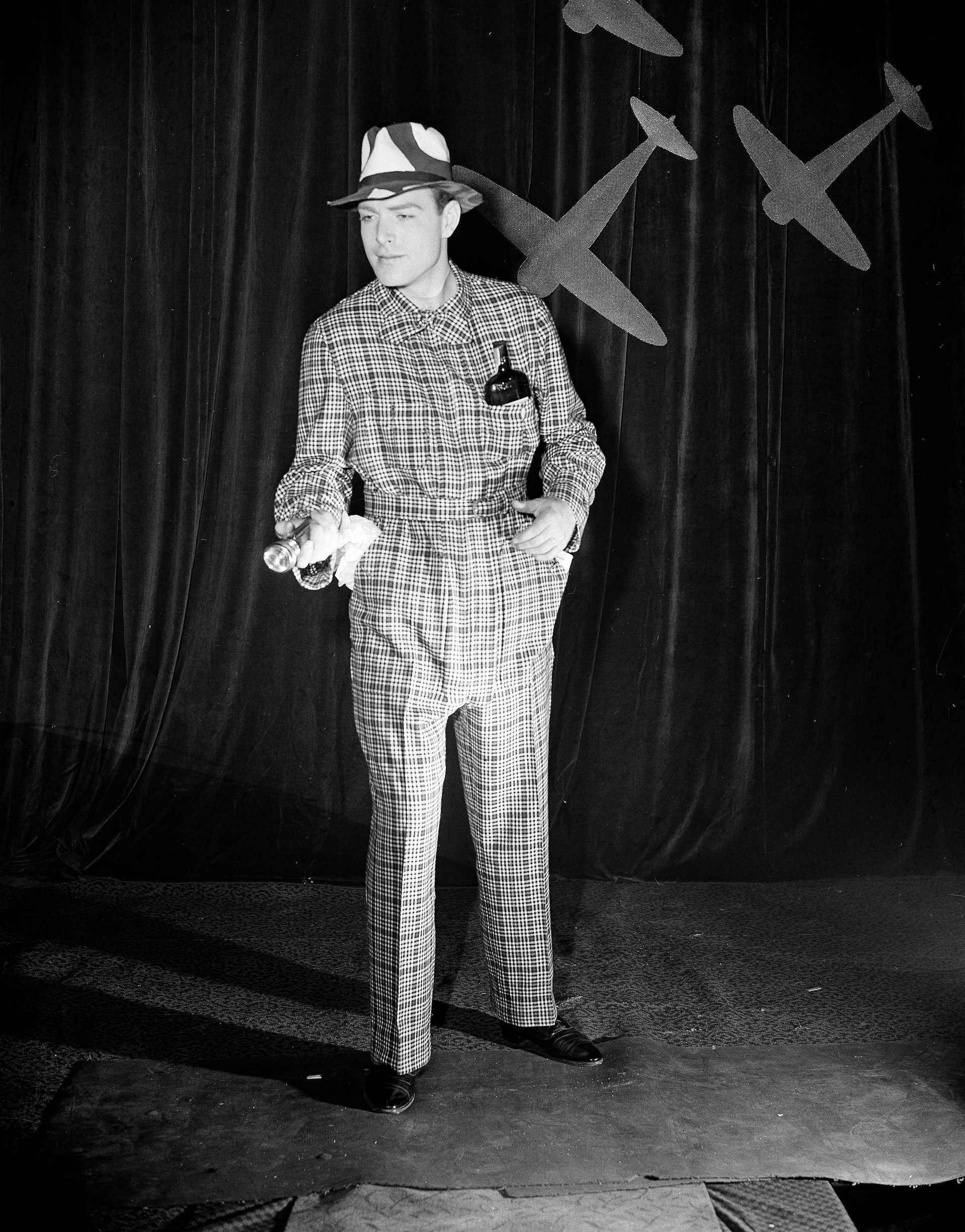

Still, for about a decade from the mid-1960s, retailers kept on pushing the male jumpsuit. The One-Suit, as it was called, touted itself as an item that worked for any occasion, given the right accessories. “It’s wearable,” boasted the 1976 ad. “And not just as a costume for first nights in the big city. But right in there. On the office front line. In the Saturday shopping stakes. Wherever you live your life.”

White-collar men don’t seem to have taken the bait: a 1967 Wall Street Journal article observed that “so far, no one has seen a jump suit on any of the commuters on the 8:07.” Instead, their most prominent male adopters during the period were more celebrity sex symbol than city-slicker: Musicians including Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Bootsy Collins, Marc Bolan, Elton John, and Elvis Presley donned jumpsuits for widely publicized performances, before the jumpsuit faded back into obscurity once again.

A jump into the future

Jumpsuits made a lot of sense for their original purpose. Designed for aviatrixes or parachutists, a single two-legged garment helped prevent flapping hems being caught in turbines or aircraft doors. For Rosie the Riveter and her blue-collar ilk, working around machinery or grease, they were similarly sensible.

As today’s white-collar workwear, however, jumpsuits border on the impractical. Unlike regular suits, you can’t adjust them according to the temperature of the room, while any accessories—belts, scarves, jackets—must be entirely removed if you wish to use the bathroom. A percipient The Onion headline puts it best: “‘Twas Hubris Led Me Here,’ Thinks Naked Woman Sitting On Public Toilet With Romper Around Her Ankles.” In fashion, writes clothing historian Anne Hollander, convenience “quickly takes second place to the delicious look of convenience.” She wasn’t specifically talking about jumpsuits, but she may as well have been.

And though the right jumpsuit can be comfortable, the wrong one is excruciating. Ideally you want to try it on in person—the fit can be complicated to get right—though that isn’t always an option for women who wear larger sizes, who are often relegated to “online only.” There seems to be an assumption, too, that only thin women are interested in jumpsuits: At the UK-based fast fashion retailer Asos, which has separate lines for women under 5 ft 4 (162 cm), over 5 ft 9 (175 cm), and larger than a US size 14 (UK size 18), jumpsuits make up about 4.5% of all Tall and Petite clothes, but just 2.3% of plus-sized options. Anna Swenson, a PR account manager in Seattle, owns two, the result of asking a Trunk Club personal stylist to send her more fashion-forward looks. “It’s sometimes harder to stay on-trend with plus-sized clothes,” she told Quartz. “So much ‘business’ wear in larger sizes is completely blah.”

But women persevere. Jumpsuits’ attributes—you don’t have to match any two items of clothing, they’re easier to pack, that certain futuristic je-ne-sais-quoi—seem to outweigh their downsides. More and more women are thus taking the plunge, often after a nudge from a personal shopper or a more assertive friend. At personal styling company Stitch Fix, “jumpsuits are outpacing growth tremendously in workwear right now. Our jumpsuit business is twice as big this year as it was last year,” women’s buying director Katherine Watts told Quartz. “It’s the new dress. It’s comfortable, but it’s a great way for her to demonstrate fashion, or reflect fashion in an easy, versatile way.”

Such a fashion-forward look isn’t necessarily the best fit for shrinking violets, or those uncomfortable with the limelight. Rosie Percy, a London-based social media editor, says jumpsuits make up 80% of her wardrobe, and tend to inspire awe from those she meets. Reactions from men and women alike are “always complimentary,” she says, “or like a ‘wow, that outfit is a lot,’ but to be honest, I thrive on it.”

The jumpsuit is bold. But for the right woman, in the right workplace, that may be exactly what’s required. Though at Reiss, the business jumpsuit is stealthy, posing as trousers and a shirt, many other options don’t shy away from the look-at-me. At Stella McCartney and MaxMara, pantsuit-inspired detailing such as grosgrain lapels or Prince of Wales check makes for a look that says “ready for business.” Emilia Wickstead’s Working Girl-inspired pink seersucker is a still bolder twist on the weirdness of office-dressing. Others are suffragette-white—a nod to the color scheme adopted by female Democrats at this year’s State of the Union address. One increasingly popular silhouette is long-sleeved and all black, with nary an inch of flesh on show.

Present retail trends seem clear: a little inconvenience is a small price to pay for an outfit with such clearly feminist origins. Wearing one puts you alongside the “can-do” women workers of the Second World War, Amelia Earhart, astronaut Sally Ride. The jumpsuit connotes a desire to be taken seriously, a willingness to think outside of the box, and a preparedness to take on the world. Women who choose to wear one to work—a conference, a meeting, an interview—are saying, in some small way, “The future is here, and I’m it. And I’m wearing a jumpsuit.”

This story is part of How We’ll Win in 2019, a year-long exploration of workplace gender equality. Read more stories here.