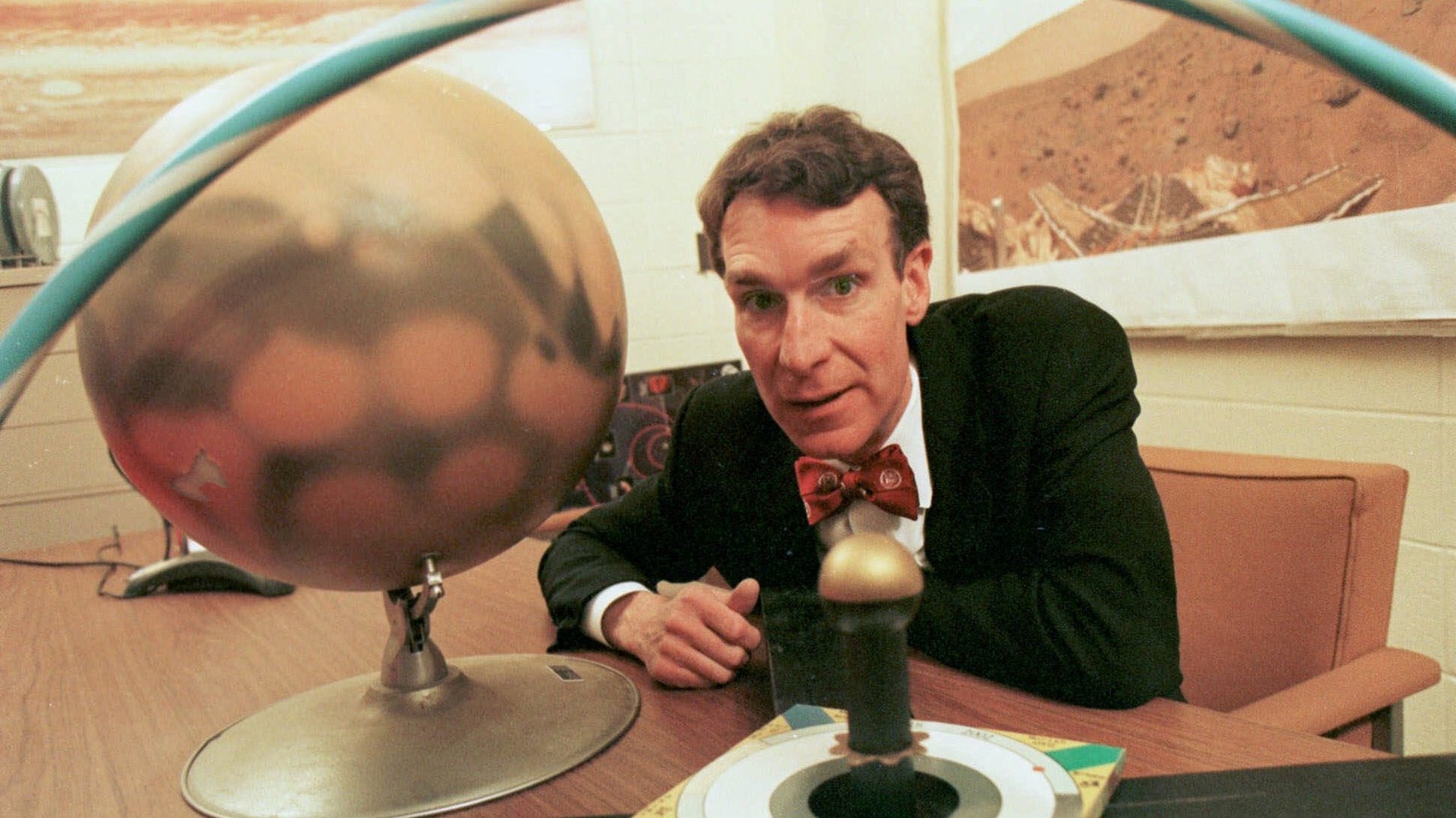

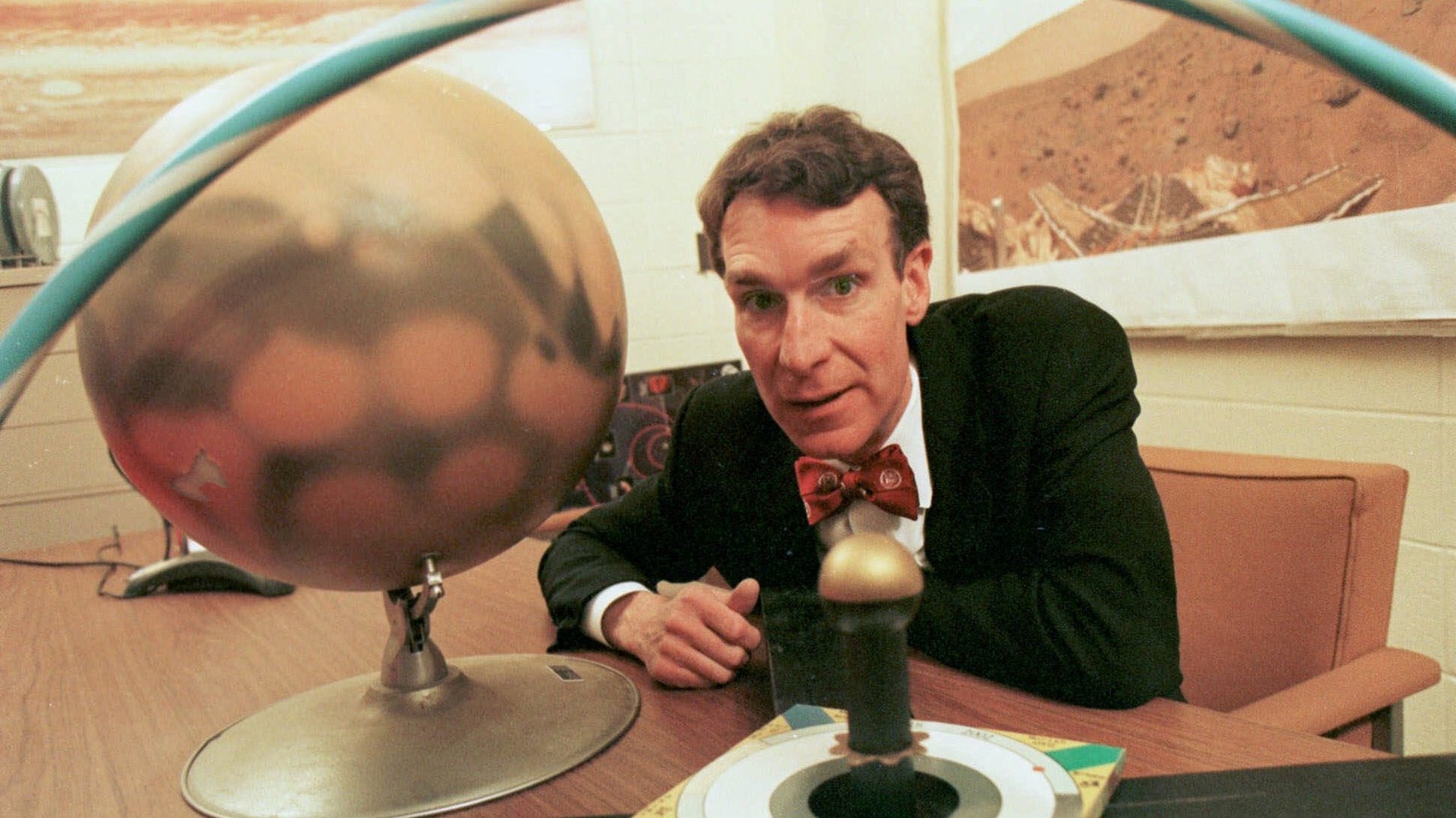

Before we knew better: “Bill Nye the Science Guy”’s legacy endures 26 years later

In this mini-series, we return to movies and TV we’ve loved to see how they depict gender. Does it hold up in 2019? Warning: contains spoilers.

In this mini-series, we return to movies and TV we’ve loved to see how they depict gender. Does it hold up in 2019? Warning: contains spoilers.

When was this show released? 1993

How does it hold up? Very well.

In the US, Bill Nye inspired an entire generation of scientists and science enthusiasts—including me.

Nye’s show, which was a product of Disney and the National Science Foundation, ran for four seasons over five years. Each episode followed the same structure: one scientific topic, covered dozens of ways, over the span of 30 minutes (about 22 without commercials).

Each episode was built to feel like flipping through the channels on your television. Viewers could catch a commercial (which never sold anything), a 1950s-style sitcom, and even a music video featuring a parody of a popular song—all tied to the week’s theme. Nye bounced around the fictitious “Nye Laboratories,” using models and props to explain scientific concepts, emphasizing key words with cheesy animations and sound effects.

Growing up, I idolized Nye. I still have a picture from when I met him at an aquarium: I was seven, and he was signing a book on ocean exploration. I learned the chorus to Science Guy‘s “Whatta Brain” parody before I ever heard the original Salt-N-Pepa “Whatta Man.”

It wasn’t just me that got hooked. The show was nominated for 23 Emmy awards, and won 19 of them. And from an educational standpoint, it worked. Across elementary and middle schools in the US (my own included), the show often took the place of science lessons on days when the teachers were off—something Nye joked about at an annual meeting of the National Science Teachers Association in the 2017 documentary Bill Nye: Science Guy.

But Bill Nye’s legacy isn’t about education. The real reason it was such a great show? It showed viewers that science is for everyone, and can be done by anyone—regardless of their age, gender, race, or ability.

Nye’s wide-eyed enthusiasm showed viewers it was okay to get excited about science. Who else could get kids into niche disciplines like podiatry—as he did when he featured a sneaker-making foot doctor on an episode about muscles and bones.

Nye and the show’s two other co-creators, Jim McKenna and Erren Gottlieb, also made it easy for kids to see themselves in the scientists on screen. There’s no official count, but several members of Nye’s team of kid scientists were girls, and many were people of color. They each had their own lab coat, demonstrated experiments to try at home, and explained concepts just like their host. Nye made a point of showcasing the work and proficiency of each of his guests. He was the Mister Rogers of science, making the laboratory his neighborhood.

Earlier this month, I had a chance to sit down with Nye at the National Press Club in Washington, DC. For the sixteenth year in a row, he was there celebrating the winners of ExploraVision, a massive science fair featuring kids from kindergarten through twelfth grade in the US and Canada. I asked him how he and his co-creators had been so far ahead of their time, featuring a diverse group of science enthusiasts well before today’s public campaigns to encourage diversity in STEM.

“I was born a white guy in the US. English is my first language. What else do you freaking want?” he asked rhetorically, agitated. Growing up in DC, he said, it was clear that people who didn’t look like him—being either people of color or women or from poorer households—had to work harder than he did for the same opportunities, or had to grow up faster than he did. “It gets back to this notion that every little kid complains about, which is life is not fair. I don’t think anybody would argue that it is,” he said. “But wouldn’t it be better if it was?”

At the time we spoke, Nye was still riding a wave of attention following the release of his new show on Netflix, Bill Nye Saves the World. After three seasons, Netflix hadn’t asked for another—although Nye was hopeful that maybe his new podcast Science Rules, would revive interest.

The rebooted show was clearly targeted at people like me who grew up on Nye. As adults, we could talk about scientific issues with grown-up themes and darker realities, like the looming threat of climate change. I didn’t like that it was riddled with pop culture references and weak nods to back to the old show. But it did inspire me to rewatch any old Science Guy episodes I could find online. At the time, Netflix had the first two seasons—but not the latter three, which aired from 1995 to 1998. Some of them are still available on YouTube through fan accounts.

Rewatching episodes of Bill Nye the Science Guy made me appreciate all the smart choices I didn’t catch as a kid. In a segment about HIV, Nye explained that there was a virus that attacked the body’s immune system, but that it wasn’t possible to transmit through touching or kissing. It was a reason, he said, to take care of our immune systems, and work to find a cure. The segment following showed a bunch of kids, some of whom had HIV, playing on a boardwalk—one of my favorite activities growing up. Nye elided the early-90s stigma attached to the sexually transmitted infection, so my 7-year-old self never latched on to it.

The point of Science Guy, Nye said to me that day in DC, was to try to make the world a little more fair, and to show everyone—particularly elementary school kids—that they were capable of making the world a better place.

Today, the show’s message is still relevant. We’re still in dire need of young scientists, Nye says, to bring us new ways to combat climate change and engineer medical breakthroughs. Luckily, he inspired an entirely new generation of scientists who can take up his role.