In 1855, Walt Whitman published his own declaration of independence

On July 4, 1855, an enterprising Brooklyn journalist took out a series of advertisements for a self-published folio of 12 poems. The book would go on to become among the most celebrated pieces of writing in American literature. Leaves of Grass was Walt Whitman’s own “declaration of independence”—from European themes and literary traditions—and a masterclass in American self-promotion.

On July 4, 1855, an enterprising Brooklyn journalist took out a series of advertisements for a self-published folio of 12 poems. The book would go on to become among the most celebrated pieces of writing in American literature. Leaves of Grass was Walt Whitman’s own “declaration of independence”—from European themes and literary traditions—and a masterclass in American self-promotion.

As a fascinating exhibition at New York’s Morgan Library and Museum shows, the book was radical in both form and content. It was a first attempt by an author at describing American life using vernacular language and strange poetic formats. “He was trying out this different type of verse; these long, free verse lines that are unrhymed, don’t have a conventional structure, not in stanzas…” explains Sal Robinson, the library’s assistant curator of literary and historical manuscripts.

Before Leaves of Grass, bards tended to idolize romantic tropes established by English poets such as William Wordsworth and Alfred Tennyson. But Whitman broke “all molds,” says Robinson. “The mold of the individual, the mold of previous poetic forms.” His opus is now studied as a seminal text on American free verse. In World War II, the US government even distributed Whitman’s poetry to soldiers, hoping his brazen, nationalistic verse would embolden spirits.

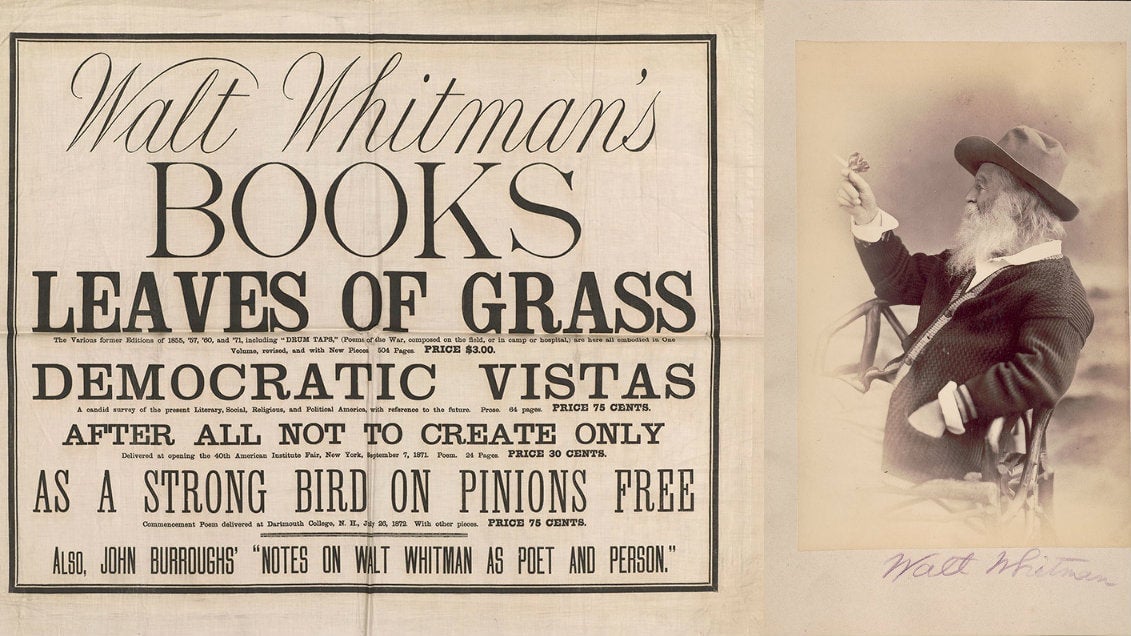

Whitman published six editions of Leaves of Grass in his lifetime. The last edition, published a year before his death, contains 389 poems and two annexes. But the first edition already harbored the germ of Whitman’s enormous ambition. Its importance “to American literary history is impossible to exaggerate,” explains English professor Ivan Marki in an article for the Walt Whitman Archive. “The slender volume introduced the poet who, celebrating the nation by celebrating himself, has since remained at the heart of America’s cultural memory because in the world of his imagination, Americans have learned to recognize and possibly understand their own.”

Father of self-promotion

Rebelling against form and content wasn’t Whitman’s only classically American trait. As the exhibition, which is on view until September 15, demonstrates, he also had a knack for marketing and self-promotion. “The public is a thick-skinned beast and you have to keep whacking away at its hide to let it know you’re there,” the author once said.

The aspiring writer, who at the time was editor of the local Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper, penned at least three anonymous critiques of his own book, including a rave review which he published in his own newspaper.

“You have come in good time, Walt Whitman!” In opinions, in manners, in costumes, in books, in the aims and occupancy of life, in associates, in poems,” exclaimed one nameless essay, penned by Whitman for The United States Review.

For the second edition of Leaves of Grass, Whitman shamelessly used an excerpt of a congratulatory letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson on the book’s spine. Without Emerson’s permission, he also submitted the letter to New York Tribune to advertise (or “share,” in today’s parlance) how the revered poet thought that his little book was “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed.”

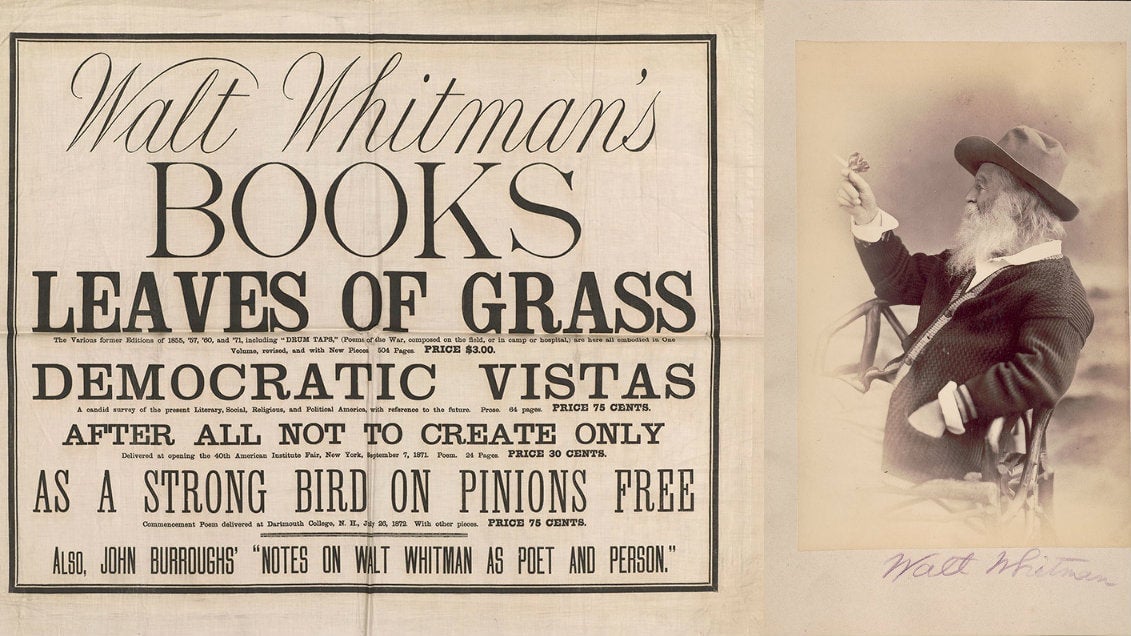

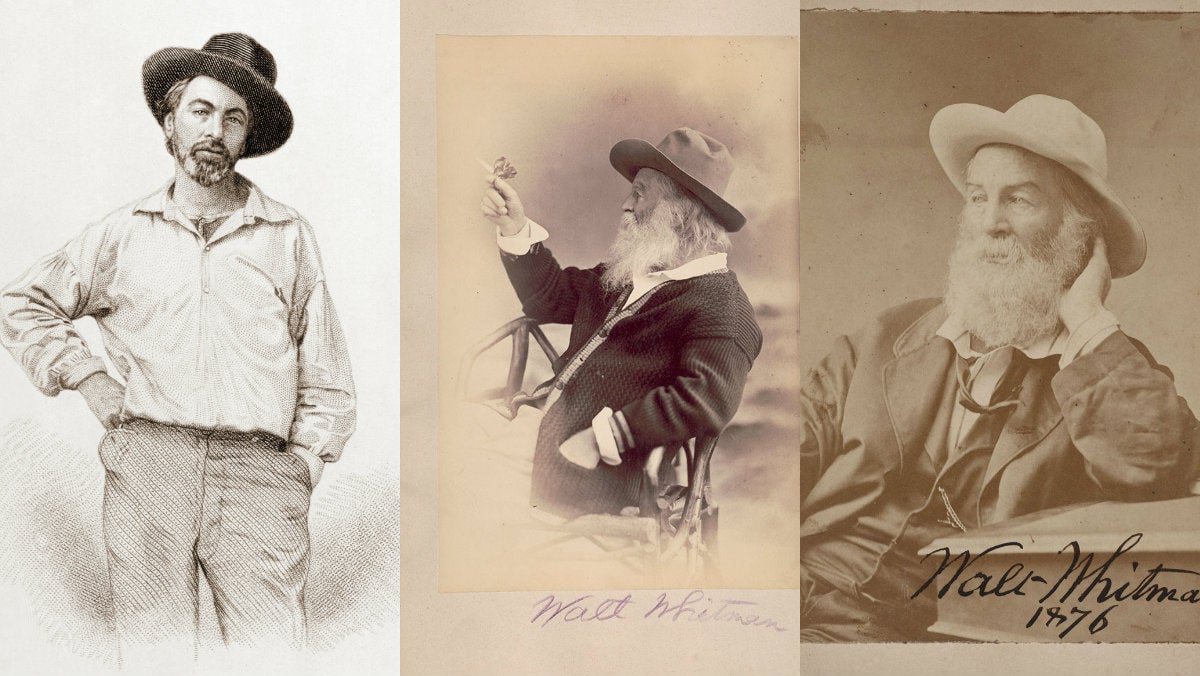

Whitman also recognized the power of images. He befriended photographers in New York and posed for 130 portraits to bolster his popularity. “That he was conscious of the power of the new medium is clearly evident in these images,” writes Robinson. “Over the course of his long life, Whitman grew extraordinarily comfortable before the camera and he would allow it to capture him over and over to the end.”

Lucky for literary fans, Whitman delivered on the promises of his sneaky self-promotion schemes. “In a notebook in 1859, Whitman wrote ‘Comrades! I am the bard of Democracy.’ Over the course of his prolific career, he made good on that claim,” explains Colin B. Bailey, the Morgan’s director. “Whitman tried to reconcile the contradictions of this country through the inclusivity and extensive body of work.”