J.D. Salinger’s son is typing up his father’s handwritten work for digital release

Unseen works of the reclusive author J.D. Salinger are being prepared for digital release in a way he might have appreciated—at least for its old-fashionedness.

Unseen works of the reclusive author J.D. Salinger are being prepared for digital release in a way he might have appreciated—at least for its old-fashionedness.

Matt Salinger, 59, tells the New York Times it will take five to seven years to finish the project he started in 2012, digging into the unpublished writing of his father, who died in 2010.

Part of the reason, as the Times reports:

He sometimes found himself getting lost in the files, entranced by his father’s voice. “Everything’s a rabbit hole,” he said. Creating digital files has been daunting, he said, because he hasn’t been able to find reliable optical-recognition software to convert the handwritten pages into electronic text, so he manually types in the material himself.

Copying things himself also limits the possibility of dissemination before any official release. His father, who once said he saw publishing during his lifetime as an invasion of privacy, just might approve.

J.D. Salinger meets the digital age

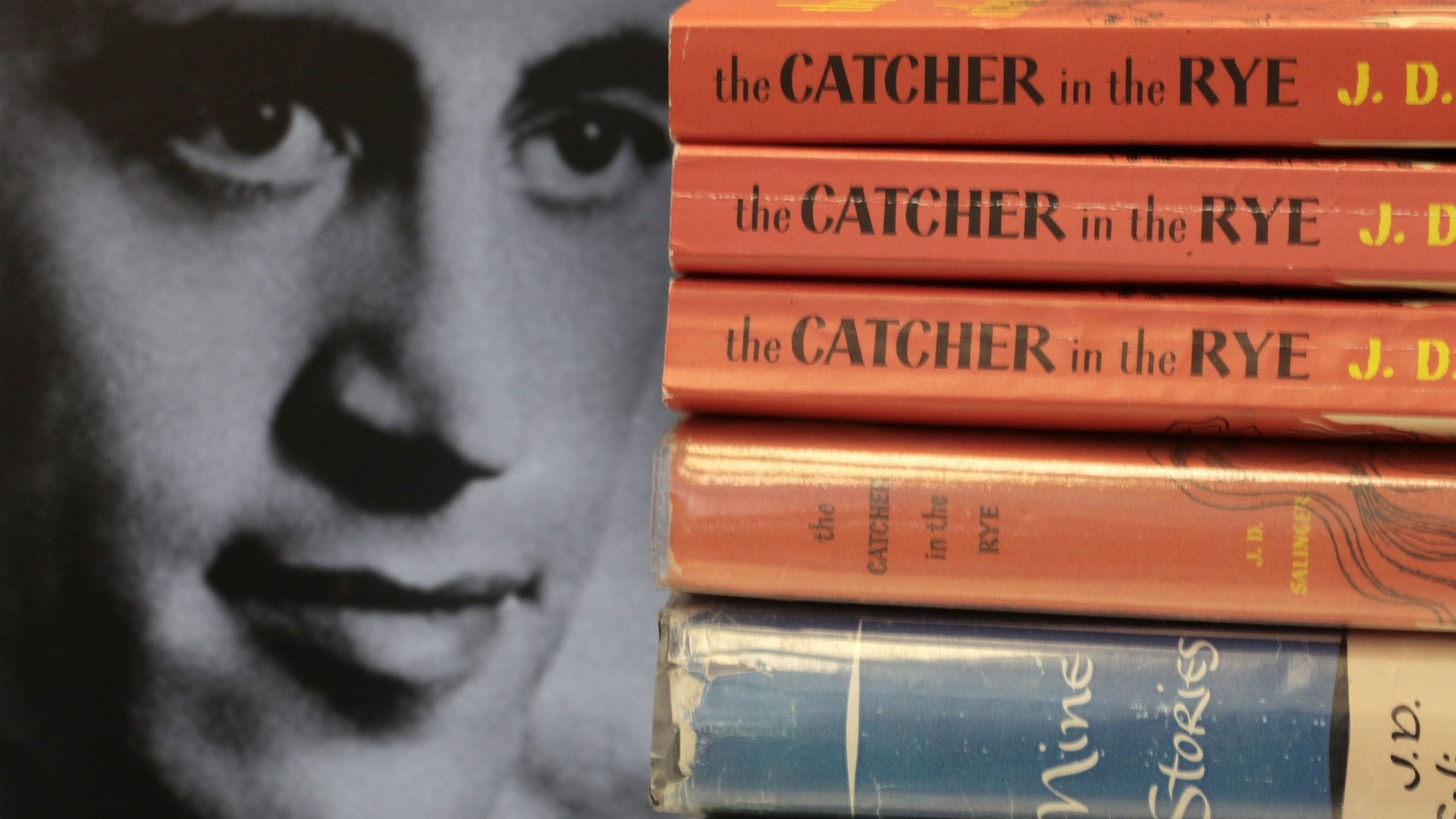

Matt Salinger has been reviewing decades of manuscripts and letters for their eventual digital publication, as well as for a New York Public Library exhibition, the first featuring his father’s personal archives. The initial digital release of J.D. Salinger’s four books (The Catcher in the Rye, Nine Stories, Franny and Zooey, and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour—An Introduction) is coming Aug. 13 from Little, Brown and Company.

His son speaks of a deep connection to his father’s work. He told Alice Develey of Le Figaro (link in French) in June that he feels an urgency to make the work he often re-reads accessible to modern audiences.

As translated by J.W. Kash: “When I re-read The Catcher in the Rye or Franny and Zooey—which is my favorite—I feel like I hear his voice. But his voice is always there, in me. I thought I was experiencing something unique because I was his son. Then I realized that I had many brothers and sisters when I read it because he had written it in a very personal way for each reader. That’s what makes his writing so beautiful. I think that when you get older, you see things differently. By rediscovering it, you will surely learn things about yourself: how much you have changed, who you were and who you have become.”

“A terrible invasion of my privacy”

Salinger’s last published work, the short story “Hapworth 16, 1924,” appeared in the New Yorker in 1965. In 1974, unauthorized collections of his early magazine stories began showing up in bookstores in San Francisco, Chicago, and New York.

Within months, the author denounced their mysterious distribution in a rare interview, telling the Times, “There is a marvelous peace in not publishing. It’s peaceful. Still. Publishing is a terrible invasion of my privacy. I like to write. I love to write. But I write just for myself and my own pleasure.”

Salinger also said he was at work on material that might not be published while he was alive.

He was right.