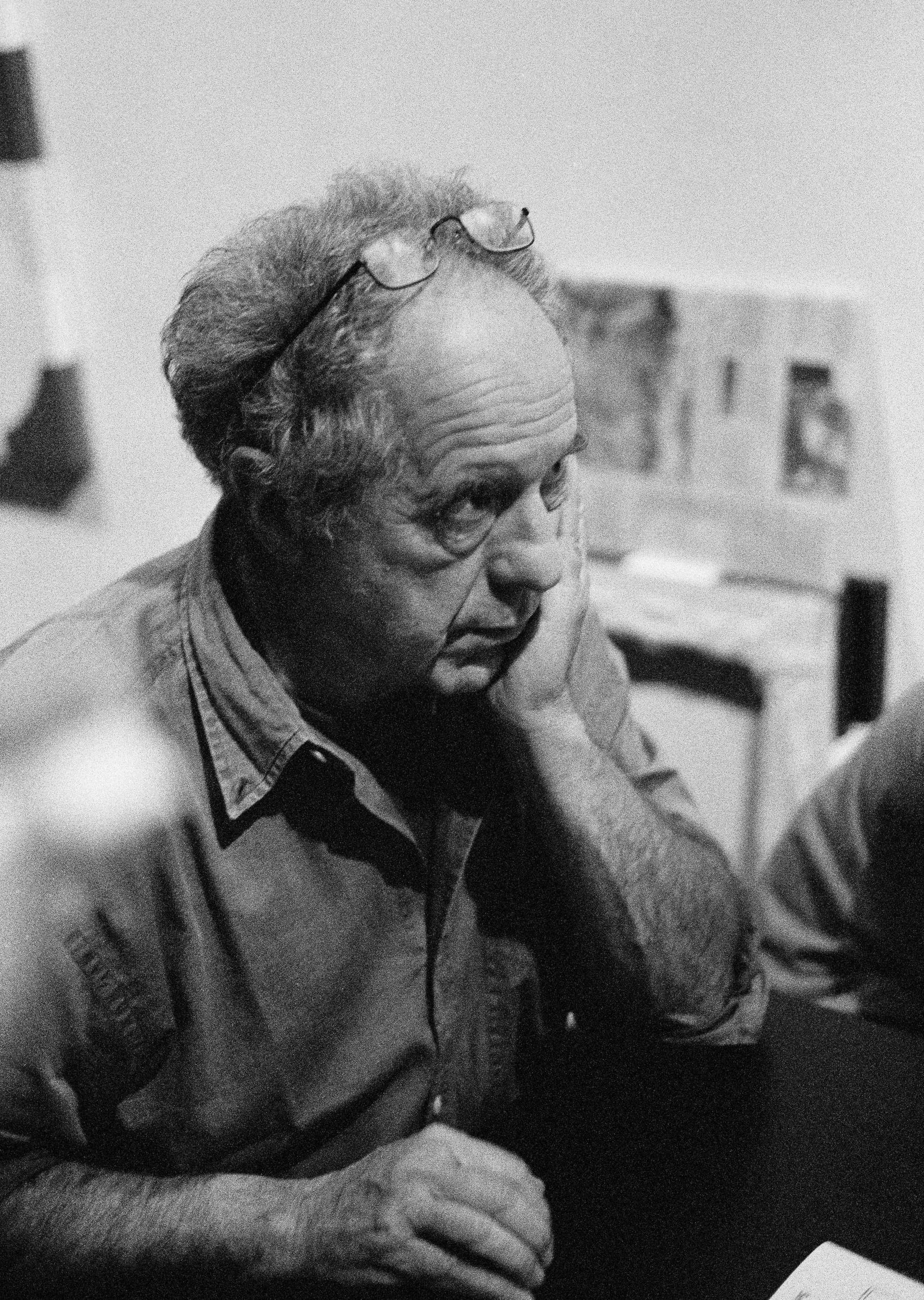

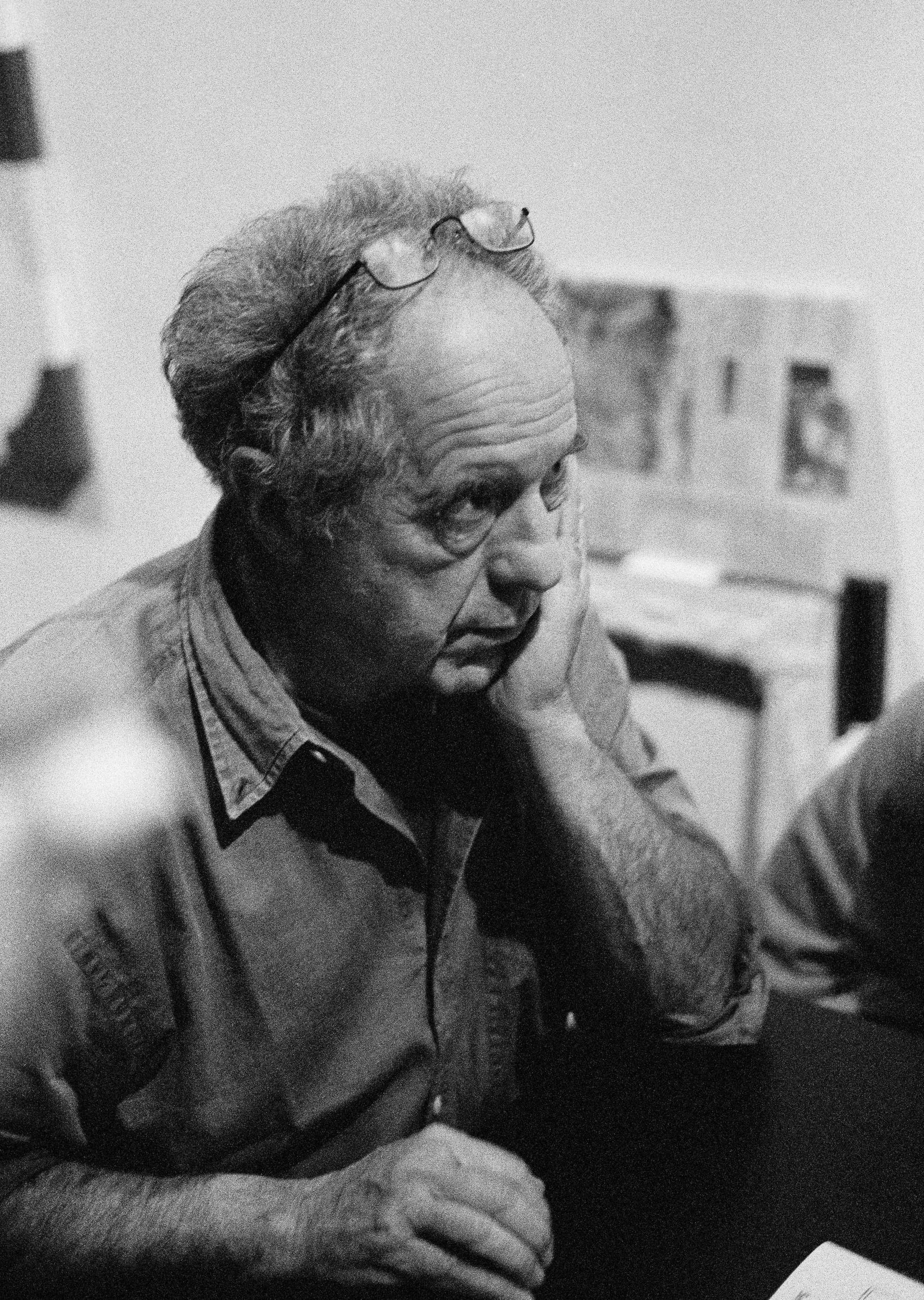

Robert Frank exposed an America that Americans weren’t ready to see

Robert Frank, the Swiss-American photographer whose seminal work The Americans showcased a melancholy and imperfect country, was a documentary artist ahead of his time.

Robert Frank, the Swiss-American photographer whose seminal work The Americans showcased a melancholy and imperfect country, was a documentary artist ahead of his time.

Known for his prodigious output that included numerous films and photo books, The Americans is Frank’s most essential work. The result of a Guggenheim Grant and two years spent on the road with his family, the 1959 book unleashed a vision of the US notable for its unsentimental and foreboding tone.

The elements of his raw, photojournalistic style—off-kilter composition, grainy details and blurred motion—are commonplace today. Yet they made his work ground-breaking at a time when the imagery promulgated by weekly mass-market magazines such as Life and Look projected an outsized American optimism. His bucking of convention would influence the generations of photographers, from to Diane Arbus to Garry Winogrand.

Frank, 94, died on Sept 9. Nova Scotia, Canada, where the New York City resident had a summer home. As the New York Times noted in his obituary, though initially fascinated with the photographic work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Frank found more meaningful inspiration in painter Edward Hopper, whose stark paintings evoke somber details of 20th-century American life, portraying an increasingly lonesome world.

That influence can be seen throughout The Americans. A view from a Montana hotel room looks on a dreary quiet town below. Anonymous figures, framed by windows, view a patriotic parade in New Jersey.

Frank exposed a gloomy emptiness at the heart of America. When The Americans was published, many reviews were scathing. Popular Photography famously called the book “a wart-covered picture of America by a joyless man.” As Bruce Davidson, a contemporary of Frank’s, said in a 2015 interview with the Guardian, ”I was a little afraid of it. It was really America in the rough. It was an America we refused to look at.”

Amanda Petrusich, writing in the New Yorker, perfectly distilled why Frank’s work was so powerful, capturing not only what he saw through his lens, but the emotions behind the people and scenes he observed: “It often feels as if his pictures aren’t of vistas or faces or rooms, but of secret American feelings.”

When mass media of the day supported a culture of unquestioning confidence, Frank saw inequality in the US growing, its citizens growing more isolated and despondent. A statement introducing a touring exhibition in 2009 reminded viewers of the shocking pessimism of the world as he captured it: “Frank depicted a people often plagued by racism, ill-served by their politicians, and rendered numb by a rapidly rising culture of consumption.” The image that graced the cover of The Americans was a stark image of segregation on a trolley in New Orleans.

Of course, Frank wasn’t the first person to notice this. The marginalized people he photographed knew full well their experience in a country that preferred to imagine it was living through a period of optimistic ascendence of its own creation.

Who would dare to puncture the myth of America when it was riding high? If The Americans was guilty of anything, it may be that it was too early.

Coming years would bring violent backlash against the US civil-rights movement, the assassinations of the Kennedy brothers and of Martin Luther King, and the protracted American war in Vietnam. If Americans didn’t feel the soul of a nation was fit to be tested in 1959, there would be no doubt in the following decade.

As many searched for a new meaning of what it was to be an American, Frank’s work was there the whole time, showing their country’s contradictions and imperfections in plain sight.