SNL’s Farrow & Ball sketch toes the line between parody and product placement

British paint company Farrow & Ball received an unexpected endorsement from the gods of comedy last weekend. The relatively niche manufacturer of eco-friendly paint and wallpaper was the subject of a fawning four-minute sketch during the Nov. 2 episode of Saturday Night Live (SNL). With a script that sounds like it was based on Farrow & Ball’s marketing spiel, the segment toed the line between parody and product placement.

British paint company Farrow & Ball received an unexpected endorsement from the gods of comedy last weekend. The relatively niche manufacturer of eco-friendly paint and wallpaper was the subject of a fawning four-minute sketch during the Nov. 2 episode of Saturday Night Live (SNL). With a script that sounds like it was based on Farrow & Ball’s marketing spiel, the segment toed the line between parody and product placement.

Consider the dialogue.

“Is it Benjamin Moore?” asks the character played by Beck Bennett noting the freshly painted walls.

“In this house, I only use Farrow & Ball, the high-end British company that offers unparalleled depth in color. Each of their 132 colors work beautifully in homes both old and new,” replies Charlotte, a style-conscious underemployed woman played by Aidy Bryant. Enunciating the word ‘color’ for comic effect, she waxes poetic on the provenance of the color names Lulworth Blue and Ammonite. The character also rationalizes why a gallon of Farrow & Ball costs $110, which is more than double the price of competitor Benjamin Moore. “It’s not just paint. It’s Farrow & Ball,” Charlotte declares, hoisting up a paint can.

The segment ends with a sign-off that’s directly lifted from the company’s origin story: “Farrow and Ball. Every color tells a story.” Farrow & Ball’s ad agency couldn’t have sold it harder.

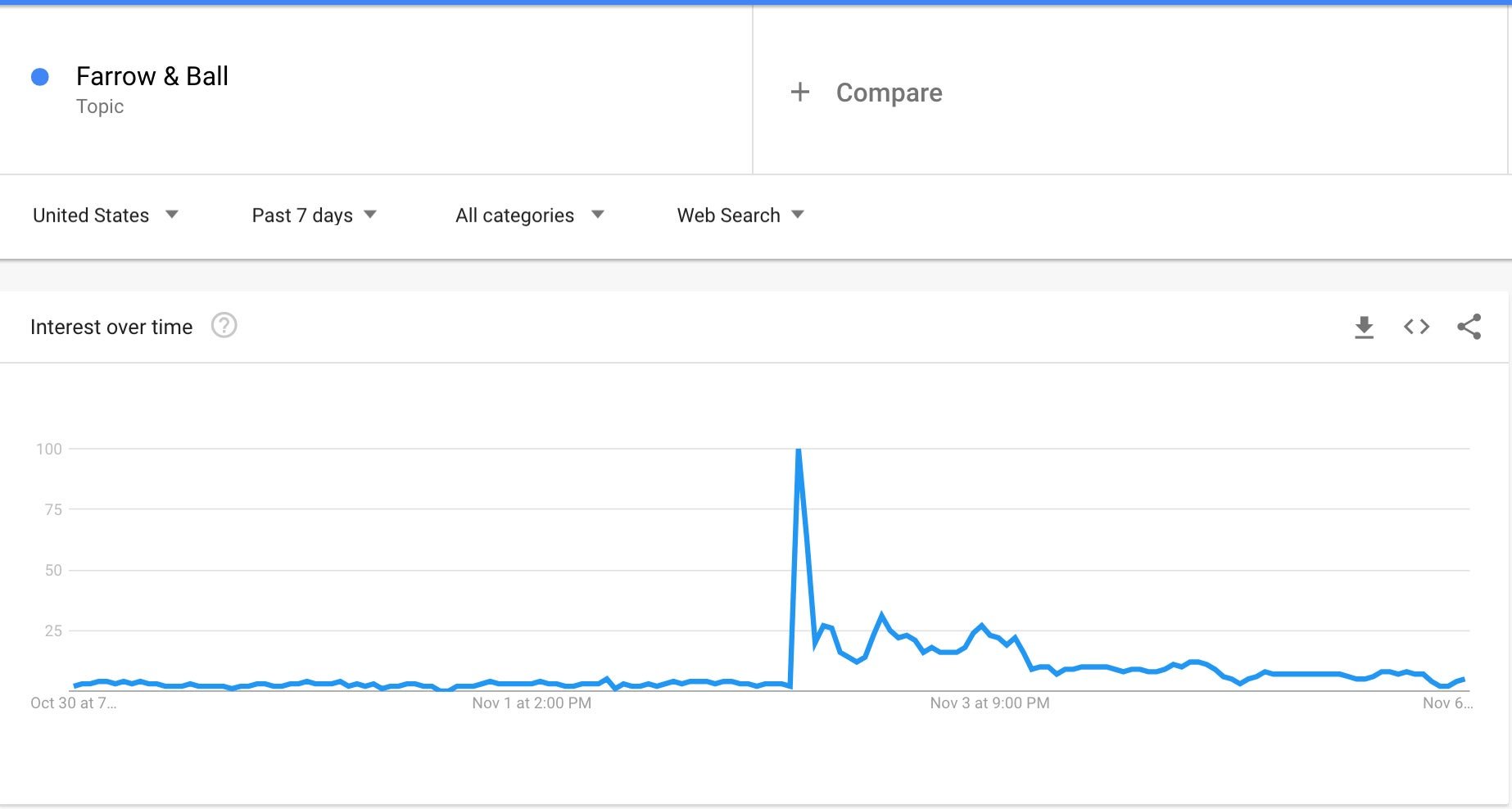

The 73-year old company based in Dorset, England confirmed that it didn’t pay for the spot. Its CEO Anthony Davey told Quartz,“It was a fantastic surprise to see the Farrow & Ball sketch on Saturday Night Live this weekend.” He added that there was a “a big spike” in the traffic to the company’s website over the weekend. It appears that several SNL viewers were trying to verify that Farrow & Ball is a real entity rather than a made-up hipster brand. Linking two random names with an ampersand is an oft-used naming trope in branding, famously skewered in the gag website Hipster Business Name Generator. What they learned was that Farrow & Ball is named after its founders, chemist John Farrow and engineer Richard Ball.

Farrow & Ball gamely acknowledged the free publicity on Twitter:

The sketch has been viewed over 1.2 million on SNL’s YouTube channel as of the time of writing. NBC declined to comment on how the Farrow & Ball segment came about or to discuss the show’s policy for sponsored content.

Commercial spoofs have been part of SNL’s 45-year history. Who can forget Mom Jeans, a riotous satire on the unflattering, high-waisted jeans marketed to women. Or Oops! I Crapped My Pants, the 1998 mock commercial for adult diapers starring a fresh-faced Ana Gasteyer and Chris Parnell. There’s also Almost Pizza, the thinly-veiled parody on DiGiorno’s, a brand of frozen pizza.

Roughly three years ago, SNL announced a new approach to sponsored content. In place of traditional commercial breaks, the show now profits from routinely integrating actual products in sketches and satirical productions. Writers have created segments with brands such as Honda, Verizon, and Apple, often without masking product names as they’ve done in the past.

Lorne Michaels, the show’s creator and producer, doesn’t see any conflicts of interest. “Comedy is a big force in the culture, and I don’t think there’s a lot of over thinking about doing commercials as there was in the late ’60s and early 70…You can’t make fun of it, and be with it” simultaneously. We have managed to find a model we all think works, and we will see,” Michaels said to Variety in 2017.

At the time, NBC’s Linda Yaccarino told Mashable that it was in the interest of improving the show. “This is really our first gift to our audience,” she explained, bristling at the term “branded content.” She argued that viewers benefit from the “continuity of having less commercial time, and on just select few occasions we will have this original content developed with our advertisers.”

But others like Los Angeles-based writer Brenden Gallagher say a clearly-defined break between spoof and sponsorship is essential. Writing for The Daily Dot, Gallagher argues that colluding with advertisers nullifies SNL’s ability to comment freely on current affairs, especially when many corporate sponsors have political interests. “If SNL wants to be taken seriously as a satire project, as it has so often been throughout its decades-long history, there ought to be a clear boundary between the jokes and the commercials that pay for them,” he said.