Money and masculinity: How wellness became big business and changed American health culture

We've never been more obsessed with our wellness, while simultaneously embracing unproven treatments and rejecting established science

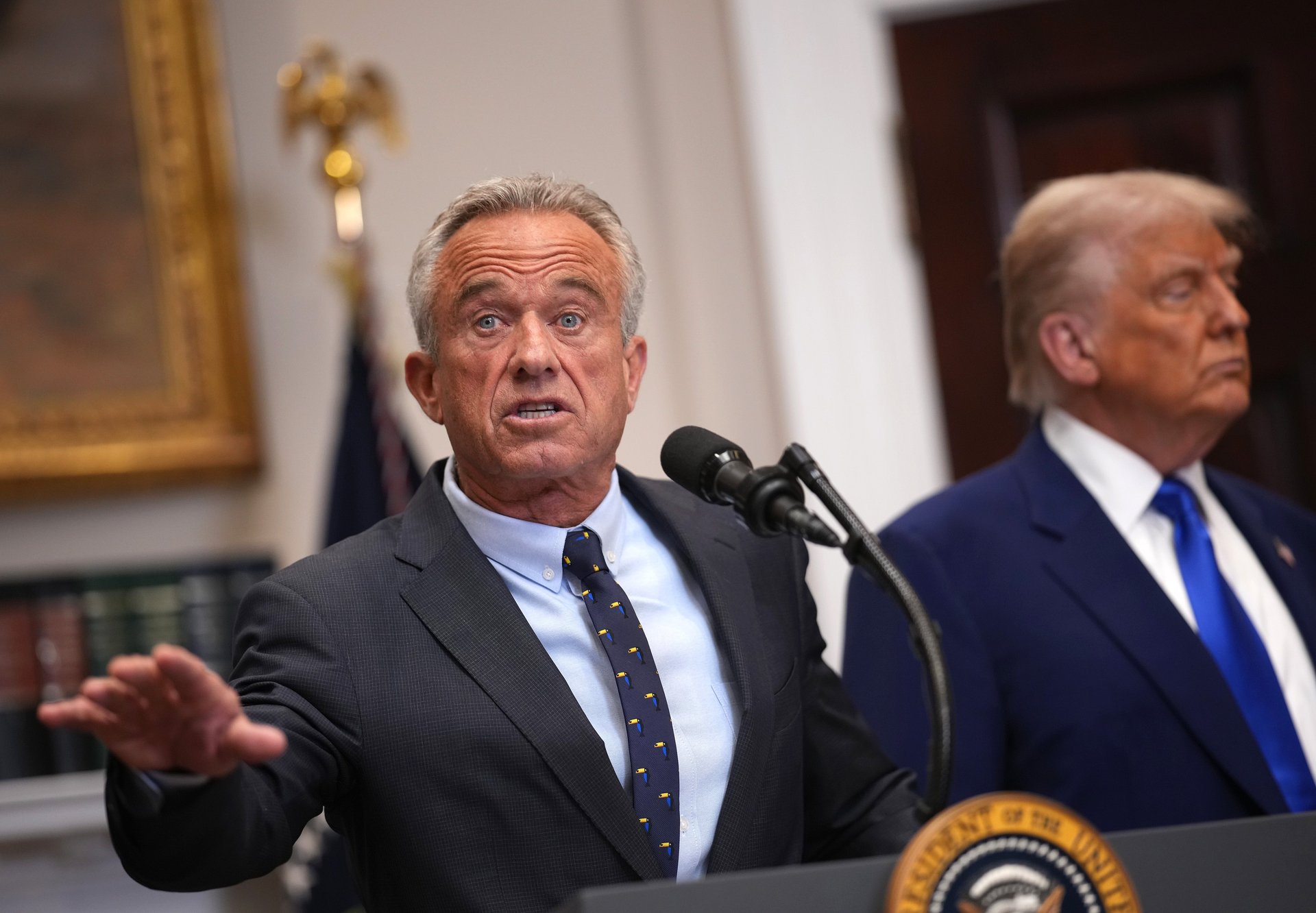

In the first months of Donald Trump’s second presidency, the world of American healthcare has seen rapid transformations, largely at the behest of his Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Kennedy’s policies range from outright rejections of established science to stringent, new food regulations. Discredited, anti-vaccine doctors such as David Geier have been tapped for positions within the federal government. Outside Washington, some states have followed Kennedy’s lead in turning away from decades of medical precedent. In Utah, Republican Gov. Spencer Cox recently signed a ban on fluoride in drinking water.

“Almost all modern societies are concerned about creating a healthy population,” said Corinna Trietel, a historian of science, medicine, and popular culture, at Washington University in St. Louis. “Unhealthy populations are not productive. They don’t fight wars effectively. They suck up a lot of money.”

The current federal government is ostensibly very concerned with public health. When Kennedy was running for president, his slogan was MAHA, or “Make America Healthy Again.” After Kennedy endorsed Trump, Trump folded that, and Kennedy’s coalition, into his own campaign.

“Our goal is to get toxins out of our environment, poisons out of our food supply, and keep our children healthy and strong,” Trump said in an address to Congress in March. “And there’s nobody better than [Kennedy] and all of the people that are working with you, you have the best, to figure out what is going on.”

Trump’s rhetoric might be somewhat belied by the reality that his administration has fired more than 10,000 federal healthcare workers and slashed billions of dollars in funding for health and science.

But in many ways, this contradiction is at the heart of American health culture: We’ve never been more obsessed with our wellness, while simultaneously embracing unproven treatments and rejecting established science.

Americans spend significantly more on so-called wellness than any other country. In 2023, the U.S. wellness industry was worth $2 trillion. China, in second place, only spent $870 billion. At the same time, a third of U.S. residents don’t even have primary care physicians, according to a 2023 report from the National Association of Community Health Centers.

“Wellness and politics have been intertwined for quite a long time,” said Mariah Wellman, a professor in the College of Communication at Michigan State University who studies social media influence on the wellness industry. “When we talk about people like RFK Jr. and other more fringe folks, it’s not surprising but it is an increasing problem that seems to be coming to a head right now.”

It’s a puzzle that people across industries – from academia to marketing and medicine – are struggling to address. How can experts encourage people to continue embracing their health, while also safeguarding against the bad science and political extremism baked into many aspects of the wellness industry?

COVID-19: A permanent turning point

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Americans of all stripes have developed an obsession with their health.

Ethan Bauley, the head of narrative intelligence at the marketing firm Weber Shandwick (IPG), analyzes online data to better understand narratives that are taking hold on social media. That includes health trends that pose challenges for the firm’s clients in the healthcare sector.

“Two things are true at the same time,” Bauley said. “One is that there is incredibly valuable, accurate information being shared online… It’s also true that people motivated by profit or ideological recruitment are using social media to influence people to sometimes make sub-optimal and even dangerous health decisions.”

This was not always the case for online wellness culture, Wellman said. Even just a decade ago, she said, wellness was largely supportive of mainstream medicine, not at odds with it.

“COVID-19 caused so much fear of the unknown,” Wellman said. “People who originally had felt like they had control over their health no longer felt that way. “Wellness influencers were able to make people feel like they had control of their health again, through accurate and inaccurate information.”

A male embrace of a female world

While the shift toward wellness transcended demographic categories, the male embrace of what was once an overwhelmingly female-focused industry is particularly notable when looking at changes in American health culture.

Jonathan Leary, who holds a doctorate in chiropractic and alternative medicine, witnessed a shift in his male clientele over a half-decade period practicing in Los Angeles.

“I never had a single male patient come to me unless they had a major trauma or major issue,” he said. “Men only came to me because it was like the last resort. Whereas my female patients were on top of it. They wanted to be preventative.”

Read more: The wellness world is getting wild and weird

Both skeptics and proponents of wellness culture noted the same shift in rhetoric that brought men into the wellness fold: American men were told by influencers that by embracing their health, they could boost productivity and success.

“Wellness went from being something quite crunchy and left-wing, to something that can be optimized and capitalized on,” Wellman said. “There was a shift in wellness language, too: It became a cutting-edge research space and [viewed] as very masculine in nature.”

Wellman noted that the shift toward a male culture is two-fold: Online wellness communities became more lucrative while male entrepreneurs supplanted female hobbyists. At the same time, there was a top-down emphasis on men’s need to become stronger.

“We saw it from the 2016 election onwards – from Donald Trump and from Fox News (FOXA),” Wellman said. “It’s very strategic because men have felt like they’re getting the short end of the stick. They feel as though they’re not being heard. And that has continued for the last almost decade.”

In some respects, Wellman added, this is the revival of a culture that began in the 1980s, when Americans were obsessed with bodybuilders and at-home fitness videos. As president, Ronald Reagan very publicly embraced caring about his own health.

Biohacking: Selling solutions

Nowhere is the masculine embrace of technology and wellness clearer than in the so-called biohacking movement.

Bryan Johnson, the face of the biohacking movement, routinely goes viral for his often bizarre health experiments: injecting his teenage son’s blood into his middle-aged body, swapping out all the plasma in his body, and using stem cells from young Swedish volunteers to alleviate his joint pain.

“We are at war with death,” Johnson told his followers at a “Don’t Die Summit” earlier this year in New York. “We’re trying to create a new era of human beings.”

There’s a decidedly male flavor to the Don’t Die community. On stage, Johnson told the hundreds of people in his audience, with an impish grin, that many biohackers got their start in the culture due to their preoccupation with “boners.” For Johnson, virility is a constant focus: “Raise children to stand tall, be firm, and be upright,” he wrote in one X post, accompanying data about the duration of his 19-year-old son’s erections.

While Johnson’s movement is rife with sophomoric humor and dubious promises about the benefits of avoiding cooked seed oil, fasting on planes, and staying out of sunlight, it’s also big business. Johnson sells supplements, urine tests, blood tests, prepared meals, protein bars, and t-shirts.

And he’s not alone.

Many of Johnson’s recommendations are couched in language which sounds scientific. Bauley, the health misinformation expert, said using technical terminology is increasingly common among those trying to make money off a booming market.

“It has always been the case that the most effective propaganda has facts and truth in it. We’re seeing people referencing research and cherry picking data to gain credibility. That tactic has become more prevalent over time,” Bauley said. “The references to scientific studies have actually increased but it’s a lot of framing and reframing the research to suit certain narratives.”

The upshot: a renewed connection to our health

When it comes to addressing the a-scientific, the exploitative, and the alarming elements of wellness culture, there is one fundamental challenge: There’s a lot of good information and positive actors, mixed in with the bad.

Over the years, Americans have spent less and less time with their doctors and received increasingly alienating healthcare services. For many people, going to the doctor is intimidating or inaccessible. Going on Instagram is easy and habitual.

Even the most extreme figures in online wellness communities spend an enormous amount of time reinforcing basic principles of healthy living: eat well, avoid excessive drug and alcohol consumption, and get good amounts of sleep and exercise. And while flashy experiments might grab headlines, there are many people creating wellness content online based on very basic health principles.

Arash Hashemi is a food influencer and the author of Shred Happens: So Easy, So Good, a cookbook based on the recipes he first developed for his Instagram page of the same name. After losing over 100 pounds, Hashemi began sharing recipes on social media, amassing more than 4 million followers.

“Social media has its challenges and certainly there are improvements that need to be made,” Hashemi said. “But it’s also helped open up conversations that weren’t happening before.

For men especially, “mental health has become more destigmatized and there’s more conversations about recovery, more on balance, more on rest,” Hashemi said. “These conversations weren’t really happening before [social media.] In many respects they were shunned.”

Hashemi said some of the most meaningful interactions he has with followers come from the parents of sick children. Having quick access to information about food that tastes good but also meets the needs of kids with cancer or diabetes was once a rarity.

“That’s that positive outweighs just about anything else,” he said. “Information is at your fingertips — you’re not reliant on a show coming on at a certain time or picking up a magazine at the store. I think that’s a really monumental shift forward as a society.”