Rich countries are destroying covid vaccines they hoarded while much of the world still waits for their first shot

Switzerland is the latest country to destroy expired doses of covid vaccine that they ordered in excess of their population's need

Switzerland is a country of 8.6 million people. As of Oct. 16, according to data compiled by Our World in Data, it had delivered a total of 16.1 million doses of the covid vaccine—or 1.85 doses per person (though only 70% of the Swiss population actually decided to receive at least one shot).

Like many other wealthy nations, the country bought many more vaccines than it needed—a total of nearly 32 million—to account for potential quality issues, or supply delays. As a result, it has large amounts of excess doses it did not use—and now won’t.

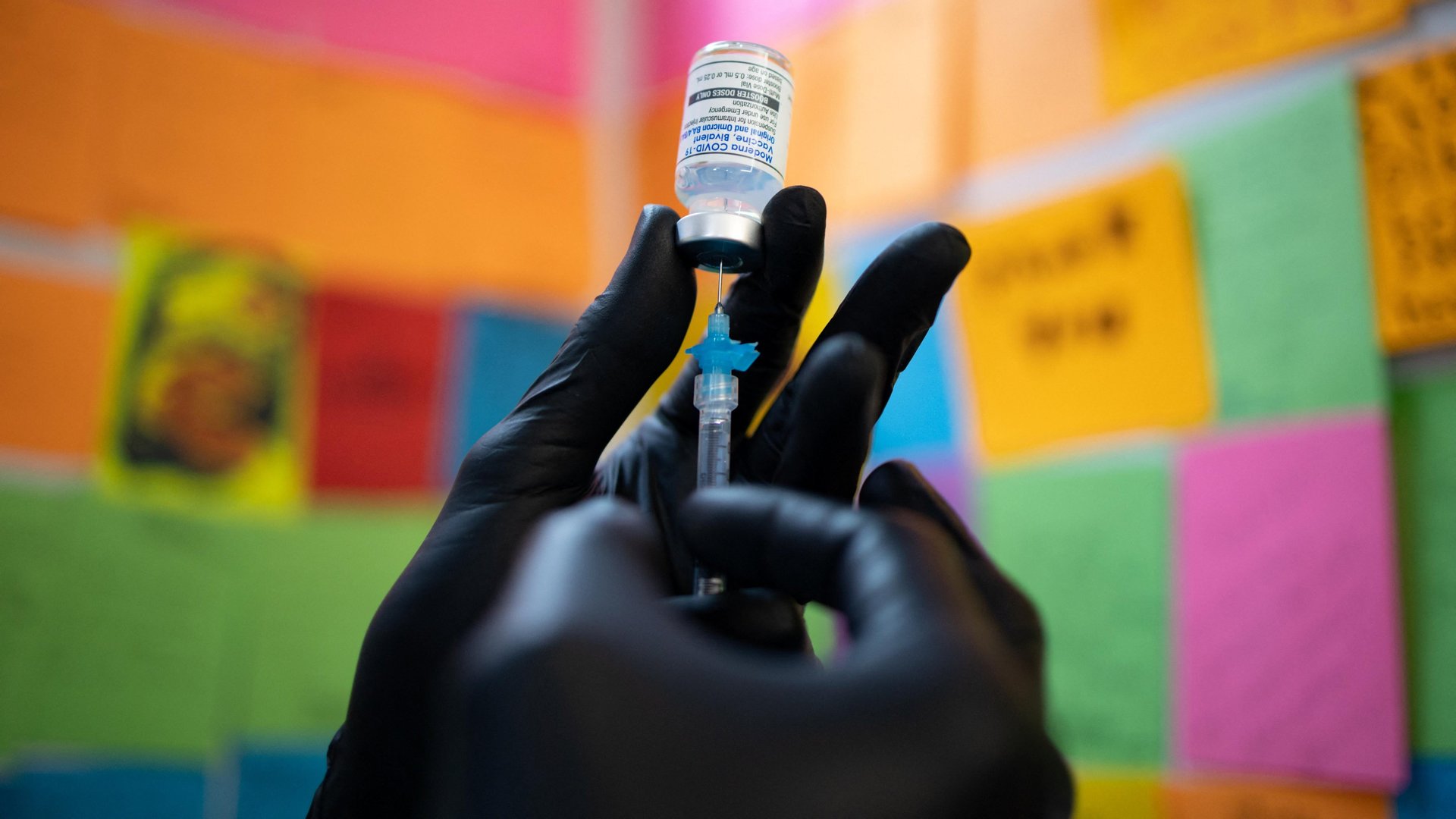

This week, the nation announced it would destroy 9 million doses of Moderna vaccines that have already expired, and more than 5 million more will likely follow, as they are due to expire in February.

By February, Switzerland likely will have destroyed more than14 million doses—or more than four times the 3.2 million doses it donated to low-income countries.

Yet with such short shelf life remaining, there is little hope that even the doses set to expire in February can be repurposed. Low-income nations have already had to reject last-minute donations of doses from wealthy countries, or destroy donated doses that arrived too close to their expiration dates, making it logistically impossible to administer them in time.

Greed led to millions of wasted covid vaccine doses

Switzerland isn’t the first country to destroy doses that could have put to better use. Earlier this year, Canada destroyed nearly 14 million AstraZeneca vaccine doses because its population preferred one of the mRNA vaccines. (The AstraZeneca vaccine, like the Johnson and Johnson one, is still commonly administered in low- and middle-income countries, as it’s easier to store, only requires one dose, and is cheaper to manufacture.)

This kind of waste is emblematic of wealthy nations hoarding doses during the pandemic, which is one of the main causes of vaccine inequality. Despite pledging a more equitable distribution and committing to sharing vaccine doses with low-income nations, rich countries have resorted to vaccine nationalism, securing all the vaccines they could get their hands on, even as large parts of the world struggled to get any doses at all.

The inequality was stark from the beginning. Early in the vaccination campaign, and before any doses had reached low-income nations, rich countries entered into agreements with vaccine makers to secure about 350% of the doses they needed, according to Unicef.

Now in the second year of vaccination, the discrepancy continues. While countries like the US and many European nations have made up to three boosters available to their citizens, only about 23% of people in low-income countries have been fully vaccinated against covid. Overall, the African continent, home to most of the nations with the lowest vaccination rates, has received only about half the doses it would need to give its population the first full round of immunization.