The immigrants’ World Cup: See all the players who crossed borders to play football

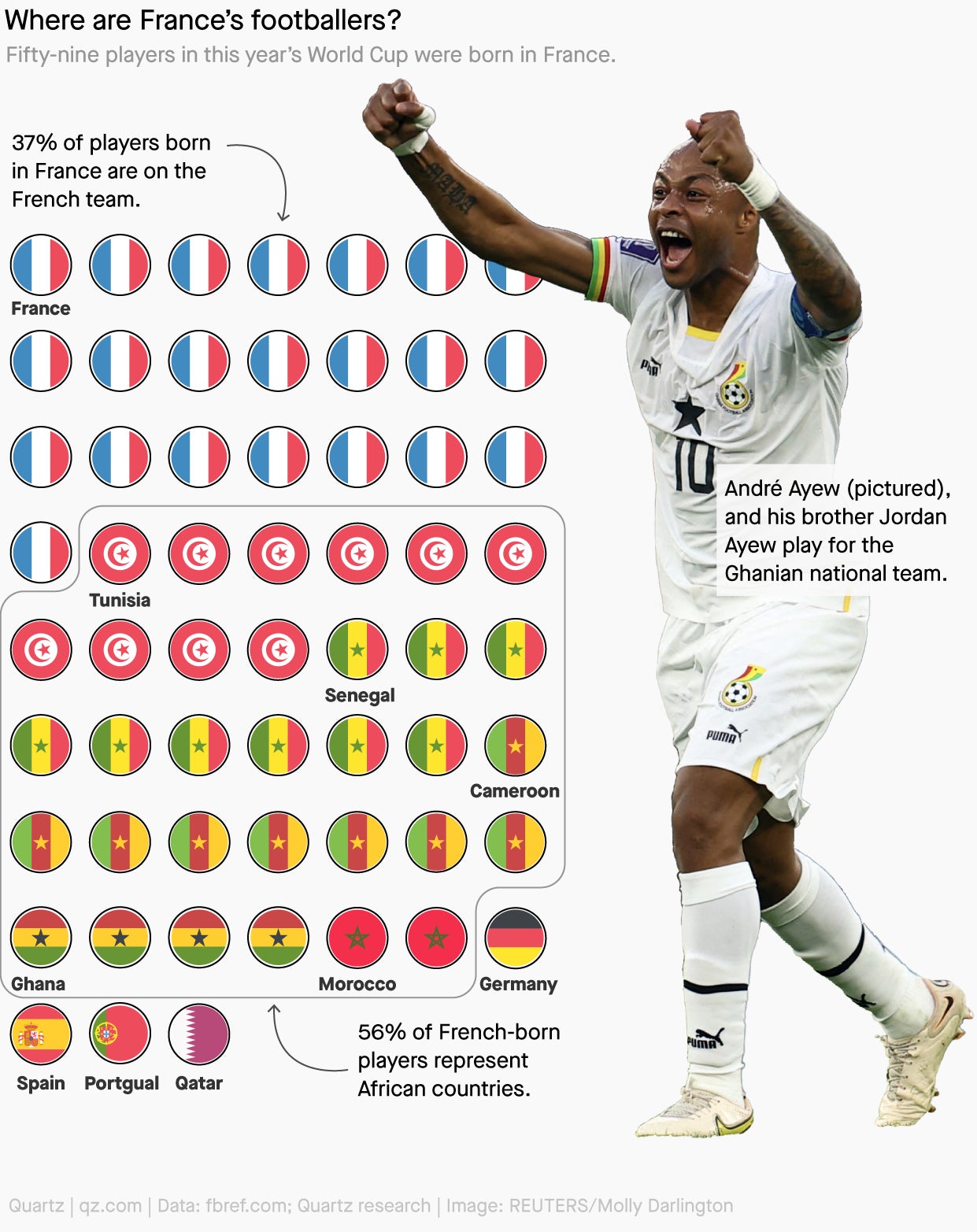

Of the 59 French-born players in this World Cup, more than half represent African teams

In the 13th match of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, the Swiss striker Breel Embolo gently held his hands up after scoring the winning goal against Cameroon. Stopping himself from celebrating was a sign of respect: He had just scored his first-ever World Cup goal against the country where he was born, and where his father still lives.

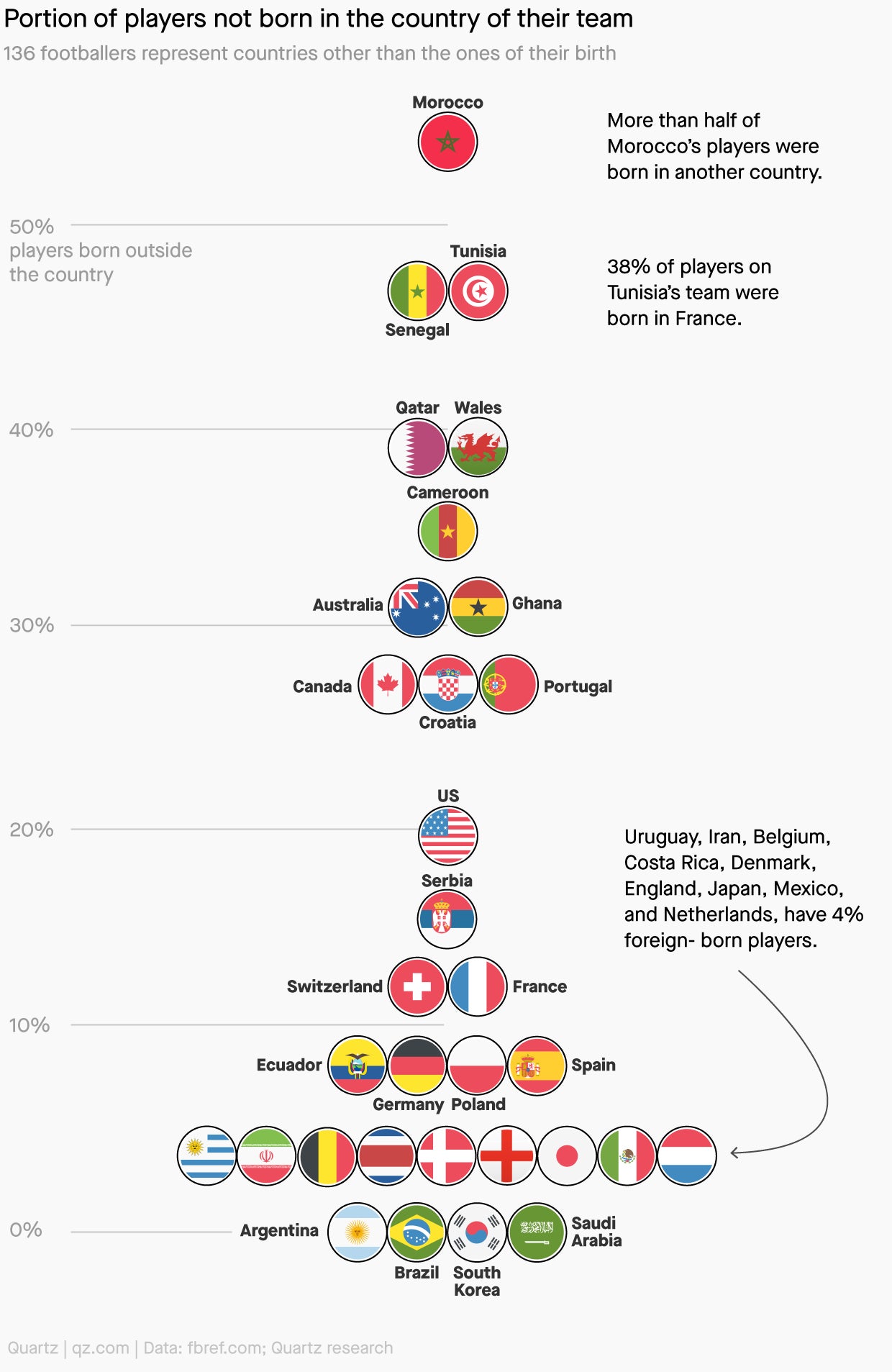

Embolo is one of 136 soccer players at Qatar representing countries other than the ones in which they were born. Most of these players play for Africa’s five teams at the World Cup. Morocco is the most extreme case: it is the only team in the tournament with more than half of its 26 players born in other countries.

This isn’t a new trend. Many earlier players have turned out in World Cups for countries other than their places of birth. Eusebio, a Portuguese great and the top scorer at the 1966 edition, was born in Mozambique. Miroslav Klose, the German striker who holds the record for the most goals at World Cups (16), was born in Poland.

But at this World Cup, an astonishing 16% of players have crossed borders to pursue their sport, shining an even stronger spotlight on the dynamics of immigration in international sport.

What determines a soccer player’s nationality?

FIFA, global soccer’s governing body, revised its eligibility rules in 2020 to insist that players must have “a genuine link” with national teams they intend to play for. The basic criteria are: place of birth, naturalization by residence, or place of one grandparent’s birth. But the rules contain exceptions for complex cases like stateless people.

One of the rules’ aims is to stop “nationality shopping,” where soccer associations seek out players who have been overlooked in their home countries. An infamous example was Qatar’s attempt to woo three Brazilian players in 2005, allegedly with cash inducements of up to $1 million.

Foiled by FIFA, Qatar chose a different route to build its national team: scouting pre- and early teens from elsewhere and training them at the sprawling Aspire Academy in Doha. It is no surprise that Qatar’s squad at this World Cup has 10 foreign-born players from eight different countries.

African teams are sourcing their soccer players from Europe

Senegal, Tunisia, and Cameroon have just as many foreign-born players in their squads. But there’s a difference.

The three countries have heavy French-born contingents in their World Cup squads. Each of the three is an erstwhile French colony. Their citizens speak French, and they have strong cultural and trade ties to France. Naturally, people from these countries migrate to France often, and go on to establish families there.

France and other European countries like Belgium and the Netherlands have well-structured soccer academies and professional clubs, of the kind often missing in Africa. The children of African migrants there pass through the system to become soccer players. But the competition at the very top is fierce. While some players of African descent like Bukayo Saka and Antonio Rüdiger have gone on to play for the European countries of their birth, many more become available to play for African teams even after representing their European homes at younger age grades.

African teams have not been shy to take advantage of this external reserve of talent. One notable move ahead of this World Cup was Ghana convincing 28-year-old Spanish-born player Iñaki Williams to turn out for the Black Stars, even as his much younger brother Nico was called up for Spain. (Ghana did something similar with two of the Boateng brothers in 2010.)

And so it is that 42% of Africa’s 130 players at Qatar were born outside the continent, mostly in France. Of the 59 French-born players in this World Cup, more than half represent African teams. At a time when Africa’s governments want to loosen colonial structures binding them to France—the CFA monetary system and military deployment, to name two—this import of soccer talent may not wane anytime soon.

Qatar 2022 has an African migrant imprint

Is Africa the source of the majority of European teams’ foreign-born players? No, and yes.

No more than two players in France’s team were born in Africa, and the same pattern holds for other European teams and Canada. England and the USA have no Africa-born players. Timothy Weah, the American forward, son of the Liberian president and soccer idol George Weah, was born in New York City.

Still, the action on the field at Qatar 2022 bears a strong imprint of African migration. France’s Kylian Mbappe, one of the tournament’s best scorers and early contender for best player, was born to a Cameroonian father, as was his teammate Aurélien Tchouaméni. Cody Gakpo, another top scorer from the Netherlands, was born to a Togolese father. The tournament’s youngest player, 18-year-old Youssoufa Moukoko, plays for Germany but was born in Cameroon.

The World Cup has, thus far, been riddled with controversy around Qatar’s mistreatment of migrant workers. But some of its records and fairy tales center migrants as well, offering not only an alternative model of globalization but also strong arguments against xenophobia. Canadians will, for instance, forever remember that their first World Cup goal was scored by Alphonso Davies, the 22-year-old born to Liberian parents in a Ghanaian refugee camp. In four years, when Canada hosts the World Cup with the US and Mexico, who knows what other records he will set—and where his teammates will have been born.