The trade war is just part of a bigger fight. An expert on how to wage economic warfare

Tariffs are just one tool of a multi-domain economic war, former U.S. sanctions official Eddie Fishman says

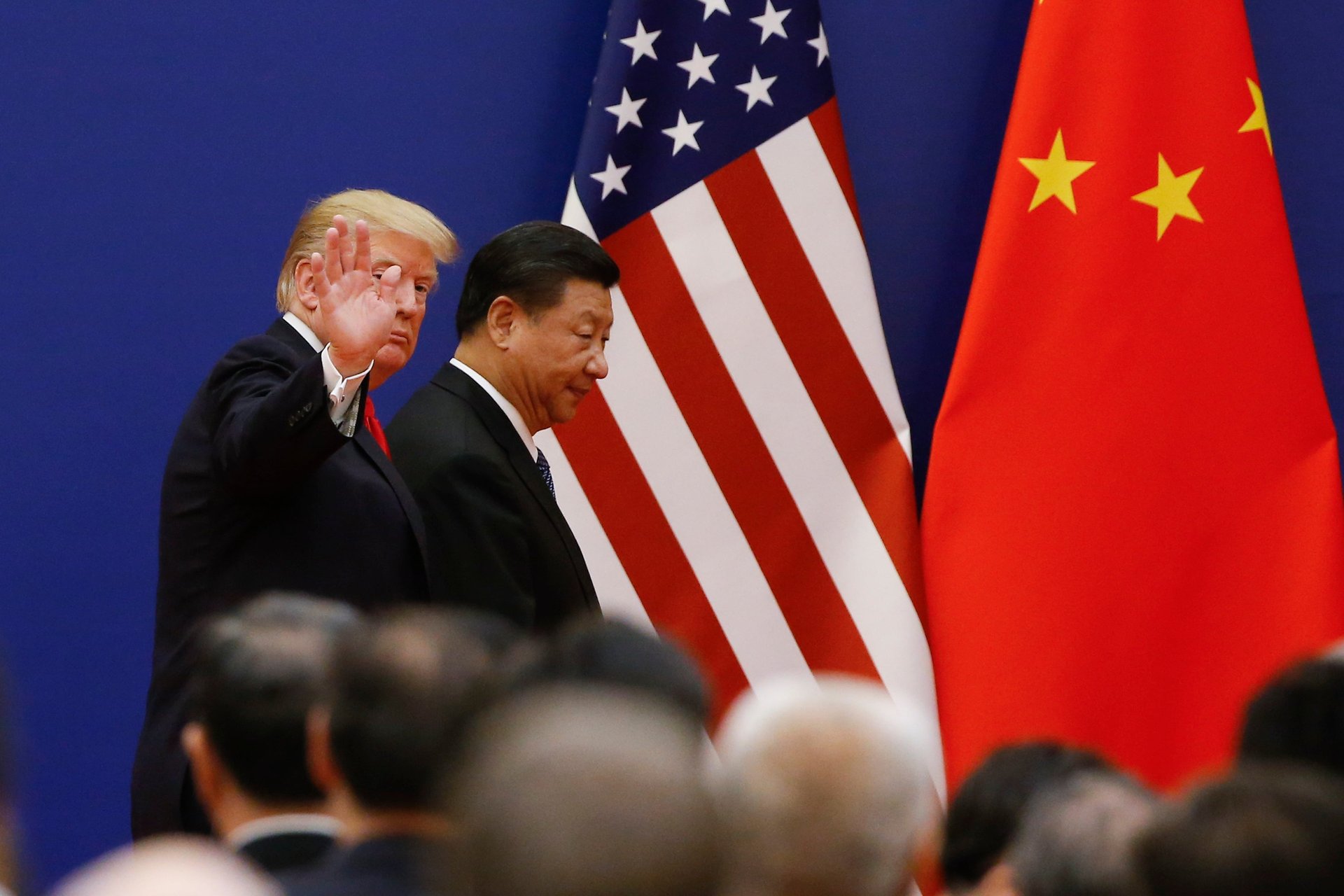

In the first few weeks of his second administration, President Donald Trump has followed through — then pulled back — on tariff threats, sending stocks tumbling into correction territory.

Suggested Reading

As Trump wields a trade war with U.S. allies such as Canada and Mexico, as well as adversaries like China, the U.S. could “wind up moving towards something that looks like autarky by default, where the only rational economic investment is in the United States,” Edward Fishman, a former State Department sanctions official, told Quartz.

Related Content

An autarky — where the U.S. economy would be self-sufficient — “is a bad future” of supply chain disruptions, higher prices, and slower economic growth, Fishman said.

“Worst of all, you’ll have a higher risk of war, because if states can’t acquire resources and markets through open trade, they’re tempted to seize them by force,” he said.

In his new book, Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare, Fishman examines how the U.S. has used sanctions, export controls, and tariffs as “weapons” in modern day economic warfare against rivals, with the technology and finance sectors at the center.

His analysis reveals that while some economic tools have successfully advanced American interests, others — like tariffs without complementary strategies — often fall short of their intended goals and can even backfire.

“I think that what’s at stake right now is not so much a trade war — it’s really a multi-domain economic war,” Fishman said. “Tariffs are just one tool, and probably not even the most aggressive tool that’s being used.”

Fishman spoke with Quartz about the evolution of economic warfare between the U.S. and China, what’s different in Trump’s second term approach to tariffs, the strategic “chokepoints” each country controls, and how both nations might navigate this increasingly complex conflict.

What “chokepoints” do the U.S. and China have?

The number one key chokepoint that the U.S. controls is the financial system and the U.S. dollar, Fishman said, which is the backbone currency of the international financial system.

The technology supply chain is another key chokepoint at the U.S.’s disposal — particularly semiconductors.

“So far, we’ve primarily relied more on the technological chokepoint as opposed to financial, but it is very clear that China is very afraid of American financial sanctions, and Chinese banks are very worried about being sanctioned by the Treasury Department,” Fishman said.

China’s key chokepoint, meanwhile, is the industrial economy, such as critical minerals and rare earths that go into chips and ammunition. In December, China banned exports of the critical minerals gallium, germanium, and antimony to the U.S.

“China dominates these areas, not just because they have the resources on their territory — a lot of times the actual mining is done in other countries — but they really dominate the processing step for critical minerals,” Fishman said.

The country also dominates in finished products such as batteries, and sophisticated goods including electric vehicles.

In the years since Trump’s first administration, China has been preparing, Fishman said, by building its own economic arsenal to retaliate against the U.S. — but not only with tariffs.

China is responding asymmetrically instead — imposing sanctions on U.S. firms such as Calvin Klein-owner (PVH) PVH and defense drone manufacturer Skydio. It has also opened regulatory investigations into U.S. companies such as Nvidia (NVDA) and Alphabet (GOOGL) — a direct retaliation for Trump’s tariffs, according to Fishman.

“As they [China] retaliate more, you’ll have a real risk of an escalatory spiral — a tit-for-tat, multi-domain economic war with China,” Fishman said, adding that it will be on Trump and Xi to figure out a more sustainable economic relationship.

Can Trump “win” with just tariffs?

“It seems like the thing he [Trump] cares most about is the trade deficit,” Fishman said.

Currently, the U.S. and China have around $600 billion in bilateral trade — about $400 billion of which is U.S. imports from China.

During his first administration, Trump wanted to close the trade deficit by selling more to China — an approach Fishman said would never work.

“The idea that you could triple American exports to China is pretty unlikely — especially if at the same time, you’re going to tell the most powerful and high technology U.S. companies that they can’t export things to China,” Fishman said.

On top of that, many U.S. companies such as Google and Meta (META) don’t have access to the Chinese market because the Chinese government has banned them.

“If he truly wants to close the trade deficit, the only viable way to do that isn’t exporting more to China, it’s by importing less from China,” Fishman said. “In some ways, tariffs will help with that, but the challenge with tariffs alone is they won’t necessarily stop our reliance on China — they may just divert trade elsewhere.”

What else can the U.S. do besides impose tariffs?

If the Trump administration wants to really reduce U.S. reliance on China, tariffs are not enough, according to Fishman.

Economic pressure alone won’t achieve Trump’s goals — any effective strategy requires both punitive measures and positive incentives to reshape global supply chains. While tariffs can discourage certain imports, they don’t automatically create new manufacturing capacity or alternative supply sources for American businesses.

The U.S. would need to invest in new supply chain relationships, also known as friend-shoring, and deeply integrate the economy with those of ally countries — a move that would require proactive trade agreements.

“The challenge right now is that Trump is really going hard on threats and tariffs, and he’s not doing as much when it comes to using trade incentives,” he said.

How can the U.S. fight an economic war?

The current age of competing with sanctions, tariffs, and export controls predates Trump, and will continue after him, Fishman said.

Currently, the U.S. “tools” for economic warfare are spread across multiple government agencies, such as the State Department and the Treasury Department, which each have different authorities and perspectives. Fishman’s suggestion is to dedicate one federal agency that is responsible for carrying out economic warfare.

“We need to have a disciplined strategic process that looks a lot like how the Pentagon prepares for and fights wars,” Fishman said. “We need to recruit and train professional individuals who can develop the right tools of economic warfare, plan for the economic wars of tomorrow and practice them, and have strategic options ready for different contingencies.”