Wall Street is paying more attention to the business risks posed by water

Droughts, floods, and water scarcity are growing worries for companies—and their big investors

From cereal maker General Mills, which relies on local farmers around the world to supply grains and nuts for its products, to tech firms like Microsoft and Amazon that need dependable supplies of freshwater to cool data centers, the list of companies vulnerable to water-related disruptions is growing.

By one estimate, some $15.5 billion worth of corporate assets have been left stranded or at risk by things like community opposition or regulatory changes triggered by water stress. Supply chain and logistical problems caused by water woes make matters worse.

The food, energy, and apparel industries are particularly vulnerable, but no company is immune. About two-thirds of big corporations inadequately manage their water risks, according to proxy advisor ISS, while 69% of listed companies reporting to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) said they are exposed to water risks with a potential value of $225 billion.

With climate change, the numbers are expected to grow.

A rising tide of investor scrutiny

Big investors are taking note. In recent years, sovereign wealth funds and big institutions like BlackRock and Franklin Templeton have been working to incorporate the water risks of companies into their valuation models and investment decisions.

There’s an ESG/do-gooder element to the attention: Access to water is a basic human right and supplies of it are shrinking around the globe. Investor scrutiny helps encourage sustainable practices, such as recharging local aquifers or using recycled “gray” water to cool an energy plant, leaving more for local communities.

Market economics also are at play. Water is a critical input along many companies’ value chains. The World Bank projects that some areas could see GDP growth rates decline 6% by 2050 if water-management practices don’t improve.

“The economy of the last century rode on the back of abundant freshwater, and we don’t have that anymore,” says Monika Freyman, vice president of sustainability for Addenda Capital, a Canadian asset manager. “We’re running out of time on water, and as an investor community we need to do more.”

Bottom-line results

But the real driver behind the interest is hard finance. Investors’ search for a competitive advantage now sometimes includes facility-by-facility reviews of corporate operations for water-related risks.

“If you’re a beverage company in an area of high freshwater risk and something happens to the supply, what is your management plan for that operation? How well are you mitigating that risk?” asks Brian Colantropo at ISS/ESG, which in 2022 launched a water risk rating tool for investors. “Those things trickle to the bottom line.”

Water is intensely local. Flood, drought, depleted aquifers, or water-quality problems can shutter factories or choke supply chains, damaging earnings. If residents get angry about how a company uses water, it can face regulatory repercussions or even lose its social license to use water.

For example, residents of Mexicali, Mexico, voted in 2020 to yank water permits for beverage company Constellation Brands, which planned to export beer from a nearly finished $1.4 billion brewery, amid persistent water shortages. Constellation has since opted to build a brewery in less-parched Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz.

“Water risk is a multidimensional operational impact risk that can affect revenues, margins, fixed-asset investments, and returns,” says Peter Adriaens, founder and CEO of Equarius Risk Analytics, a fintech firm that uses sophisticated mathematical modeling to help investors understand companies’ water risks.

Done right, plugging good water-risk data into broader valuation models can pay dividends. Adriaens says he has seen investors juice their annual returns by 30 to 60 basis points.

How it works

Confronting water risks is complicated. An array of frameworks, filters, and helpers—ranging from the UN and NGOs to Fortune 500 companies, ratings agencies, proxy advisors, and technology startups—fill knowledge and capability gaps and add to the confusion.

An investor toolkit from the nonprofit Ceres, an advocate for sustainable investment, suggests a progression from understanding and setting priorities to analyzing stock, asset class, and portfolio risks and engaging with companies to drive needed change.

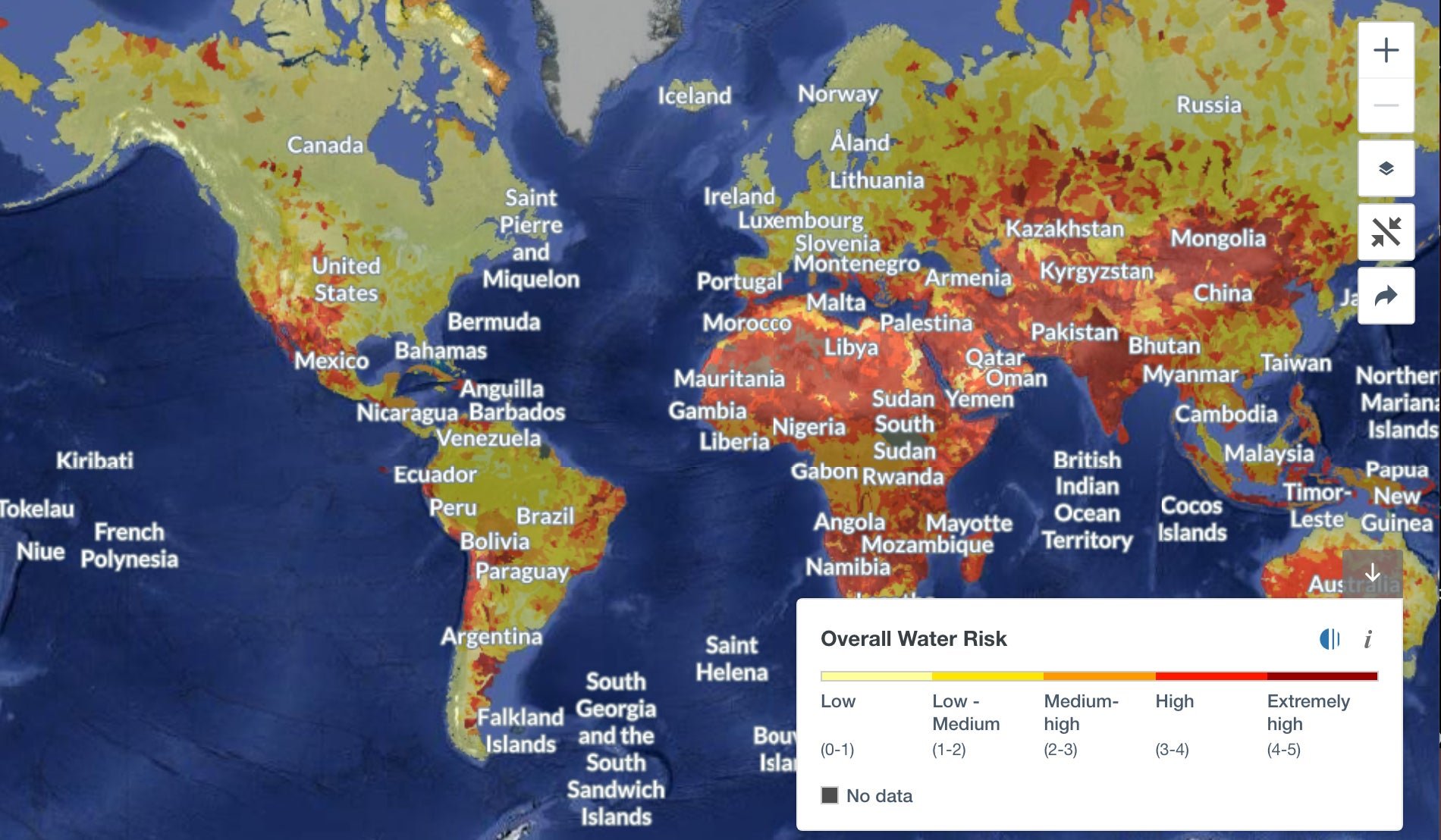

The process typically starts with maps. The World Resources Institute publishes popular maps that show levels of water stress down to the neighborhood level, anywhere in the world. Investors overlay those with maps of a company’s global operations to identify areas where operations and assets might be at risk.

For example, BlackRock recently geolocated about 80,000 properties owned by real estate investment trusts (REITs) in 74 countries, and then overlaid WRI’s maps and other analytics to understand their water-risk exposures. (It used REITs because of the location details in their filings.) While fewer than 30% of those properties are in high water-stress regions today, the percentage is expected to double by 2030.

BlackRock plans to expand its analysis to companies in other sectors, such as agriculture and energy, and those with at-risk global supply chains. “Companies’ exposure to water stress is set to increase dramatically in the decades ahead,” its report on the study states.

Water risk monetizers, models, and valuation tools

The trick comes in translating those physical risks into a measurable material or financial risks. While water is critical to most corporate operations, it’s also intensely local and almost always underpriced, making it difficult to determine its true value to a company’s operations.

A variety of players offer specialized tools to help investors create alternative valuation models. For example, Ecolab’s Water Risk Monetizer 2.0 and the Bloomberg Water Risk Valuation Tool seek to create “shadow prices” for water that reflect its true value for use in risk calculations, as opposed to the price paid.

It’s an increasingly data-driven process, with a host of startups with names like Bluerisk, Aquantix, and Equarius employing sophisticated AI-driven models to derive the influence water has on systemic risks and profitability.

“Everybody has risks,” Equarius’s Adriaens says. “The question is how much are they underpaying for the risk they’re exposed to.”

Water is now showing up in shareholder resolutions

The final piece of the puzzle is often engagement. Investors are demanding more often that companies better disclose water-related exposures, such as amounts used, conservation efforts, costs, and importance to the value chain. Many of those discussions occur behind closed doors, but water is showing up in shareholder resolutions as well.

For example, this year’s proxy at food company Kraft Heinz includes a resolution demanding the company identify water risk exposures in its supply chain, as well as preparations for future “water supply uncertainties.” Kraft Heinz responds that it already produces a suitable report on water risk.

Investor engagement efforts accelerated last year with the launch of the Valuing Water Finance Initiative, a campaign by 89 institutional investors managing a combined $17 trillion in assets to evaluate and engage 72 global companies on six pillars of good water stewardship.

Kirsten James, senior program director for water at Ceres, says investor interest in water risk is following the same trajectory as climate risk, only a decade behind. “As the long-term risks become clearer, we’re seeing growing investor momentum around water,” she says.