Timeless management advice from a book left in a coffee shop

No-Nonsense Management: A Primer for Managers was written in 1977 by Richard S. Sloma, a former executive and the author of a suite of managerial reference books (other titles include No-Nonsense Planning and No-Nonsense Government). Bantam paperback versions of No-Nonsense Management appeared in 1981. Somehow over the next 36 years one of those copies ended up on the crowded shelf of free books at Coffee Cartel in Redondo Beach, California.

No-Nonsense Management: A Primer for Managers was written in 1977 by Richard S. Sloma, a former executive and the author of a suite of managerial reference books (other titles include No-Nonsense Planning and No-Nonsense Government). Bantam paperback versions of No-Nonsense Management appeared in 1981. Somehow over the next 36 years one of those copies ended up on the crowded shelf of free books at Coffee Cartel in Redondo Beach, California.

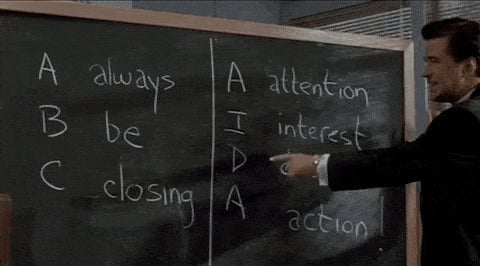

I’ve thumbed through a lot of books at Coffee Cartel, but never one quite like this. What jumped out from the pages was not so much Sloma’s bare-knuckled writing style but the enthusiastic highlights and notes of the book’s previous (and presumably original) owner. The book’s Reagan-era corporate mindset and the note-taker’s wholehearted embrace of it makes for entertaining reading, like a dialogue between Alec Baldwin’s Blake in Glengarry Glen Ross and The Office’s Dwight Schrute.

Let’s take a look at some of the top lessons.

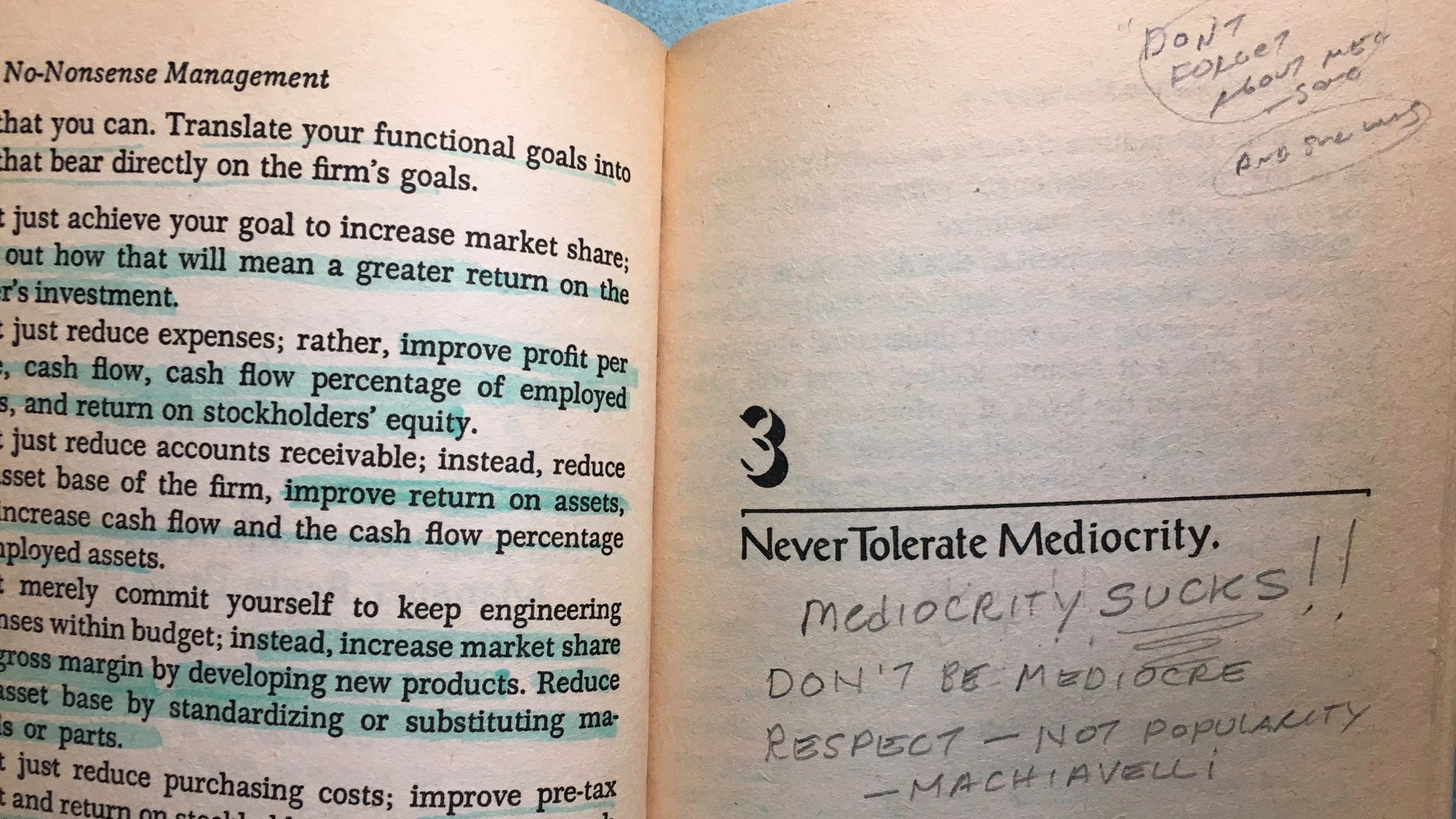

Never tolerate mediocrity

“If you’re going to achieve excellent results, not only must you perform excellently, but so must level upon level of your organization. Your people must identify you with an expectation of high levels of performance. The minute you accept mediocrity, you lower the performance levels of your entire organization.”

This made the a big impression on our note-taker. “Mediocrity SUCKS!!” s/he wrote in block capital letters. “DON’T BE MEDIOCRE. RESPECT—NOT POPULARITY—MACHIAVELLI.”

This is the first of several references to Machiavelli in the marginalia. There are also two song titles written in pencil at the top of this page: Simple Minds’ “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” and “And She Was” by the Talking Heads. Both songs came out in 1985, providing a helpful clue regarding when our reader made these notes (or at least regarding his/her musical tastes).

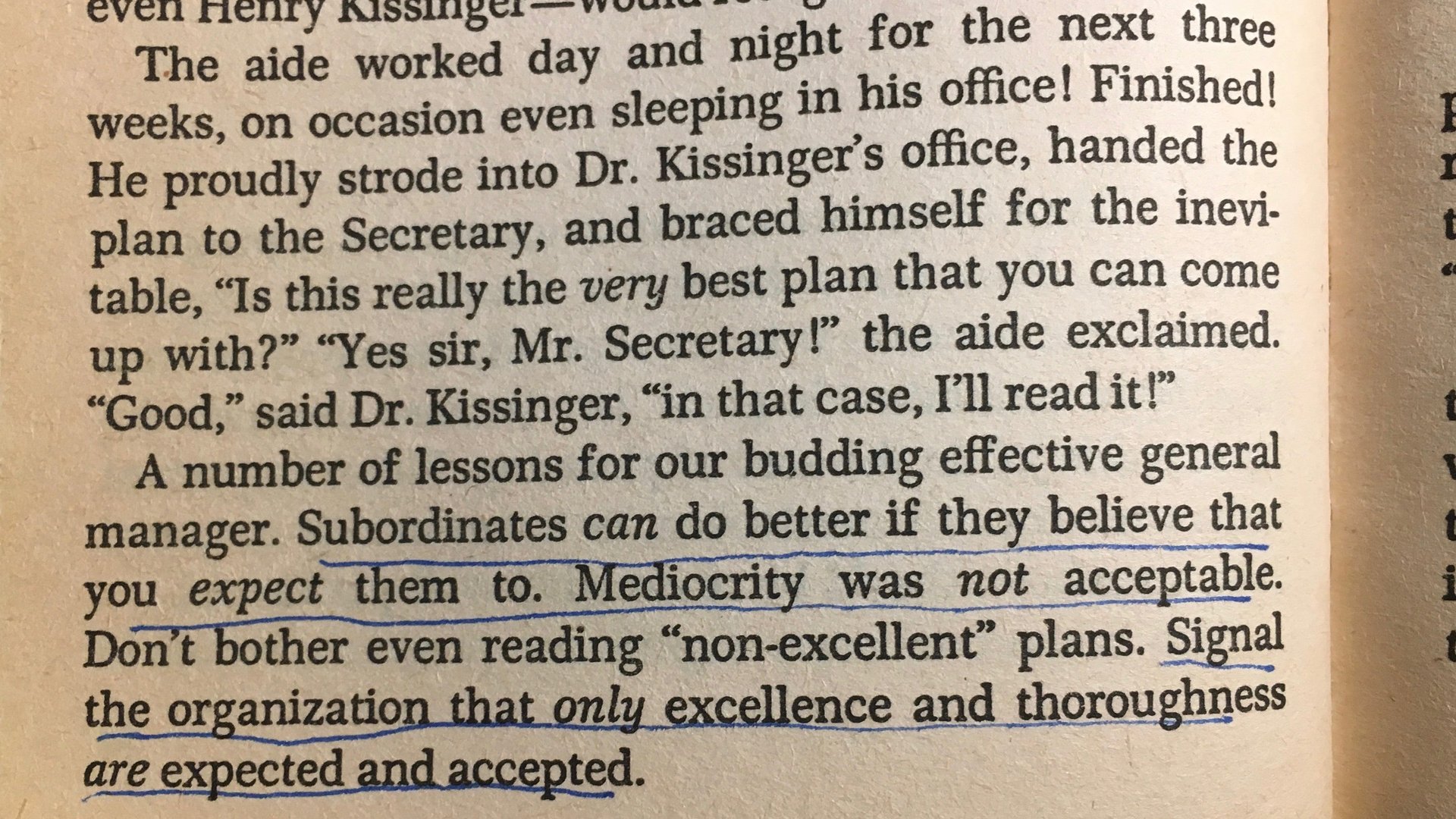

If it’s not excellent, it’s not worth your time

“Subordinates can do better if they believe that you expect them to. Mediocrity was not acceptable. Don’t bother even reading “non-excellent” plans. Signal the organization that only excellence and thoroughness are expected and accepted.”

No notes here, but the annotator did underline this passage. Maybe s/he was struck by the sentences themselves, or maybe the idea was really driven home by the ensuing anecdote Sloma used to illustrate the point. The story involved Henry Kissinger, the former US Secretary of State and National Security Adviser, who apparently once asked a subordinate for a report and refused to so much as read a draft until the employee spent more than a month sleeping in his own office perfecting the document. Ah, management!

Getting 95% of the way there is enough

“We live, at best, in a 95% world. We seek perfection, but it successfully eludes all of us. Far too often, we achieve results well short of even the 95% level potentially available. But 95% isn’t really all that bad!”

This seems like something of a turnaround from Sloma’s earlier, unrelenting drive for excellence, but it struck a nerve. “F— perfection!” our note-taking reader has written. (That is not our censoring; the reader put those dashes in there. A strong personal aversion to foul language? Kids reading over his/her shoulder? We’ll never know.)

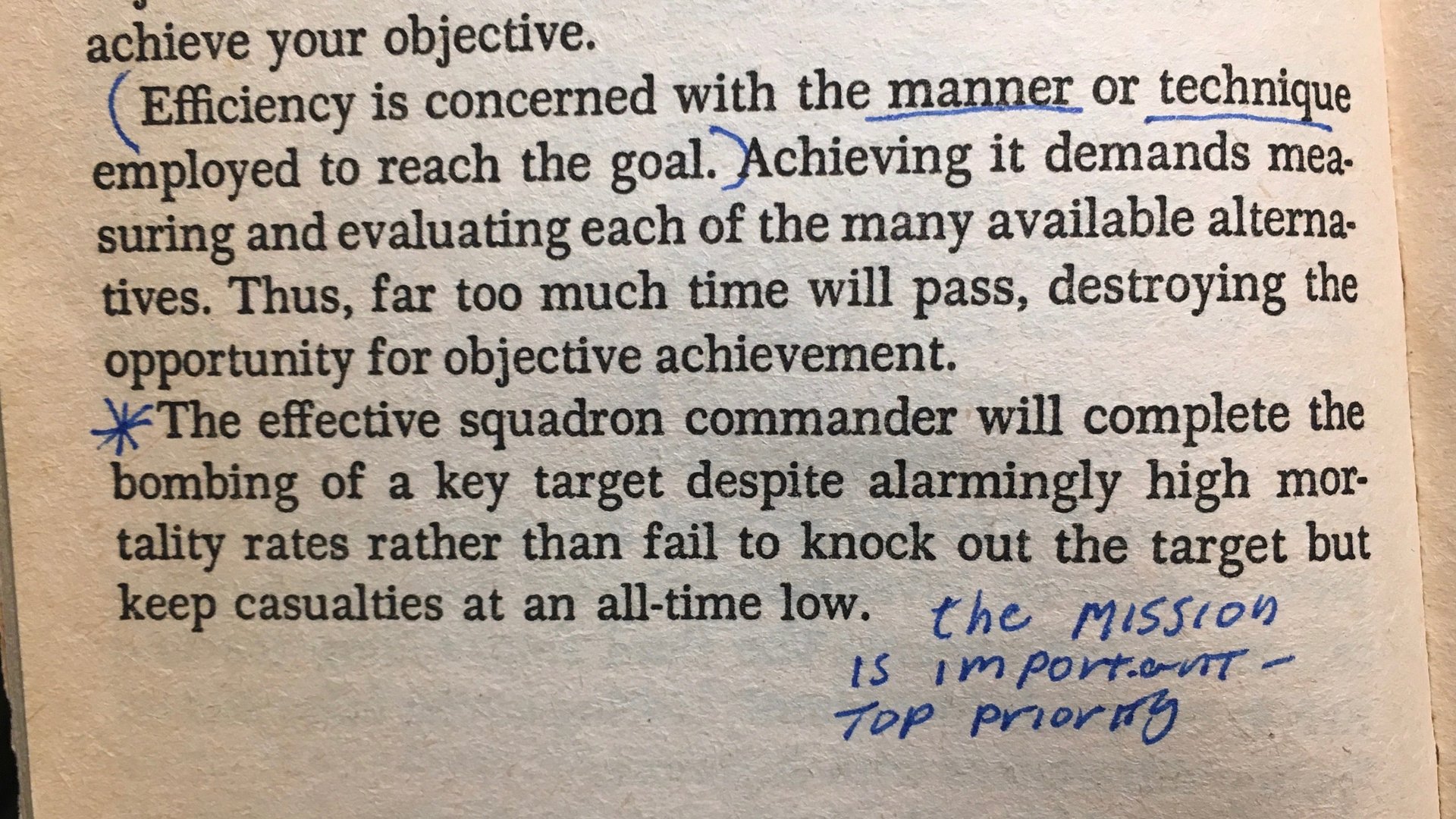

Don’t be afraid of high casualty rates

Wait, what?

“The effective squadron commander will complete the bombing of a key target despite alarmingly high mortality rates rather than fail to knock out the target but keep casualties at an all-time low.”

We just got done talking about the importance of a good plan. Wouldn’t it be better to seek an option that gets the job done without “alarmingly high mortality rates”? Reader? “The mission is important—top priority,” the margin note says confidently. Okay then.

If a boat leaks, fix it

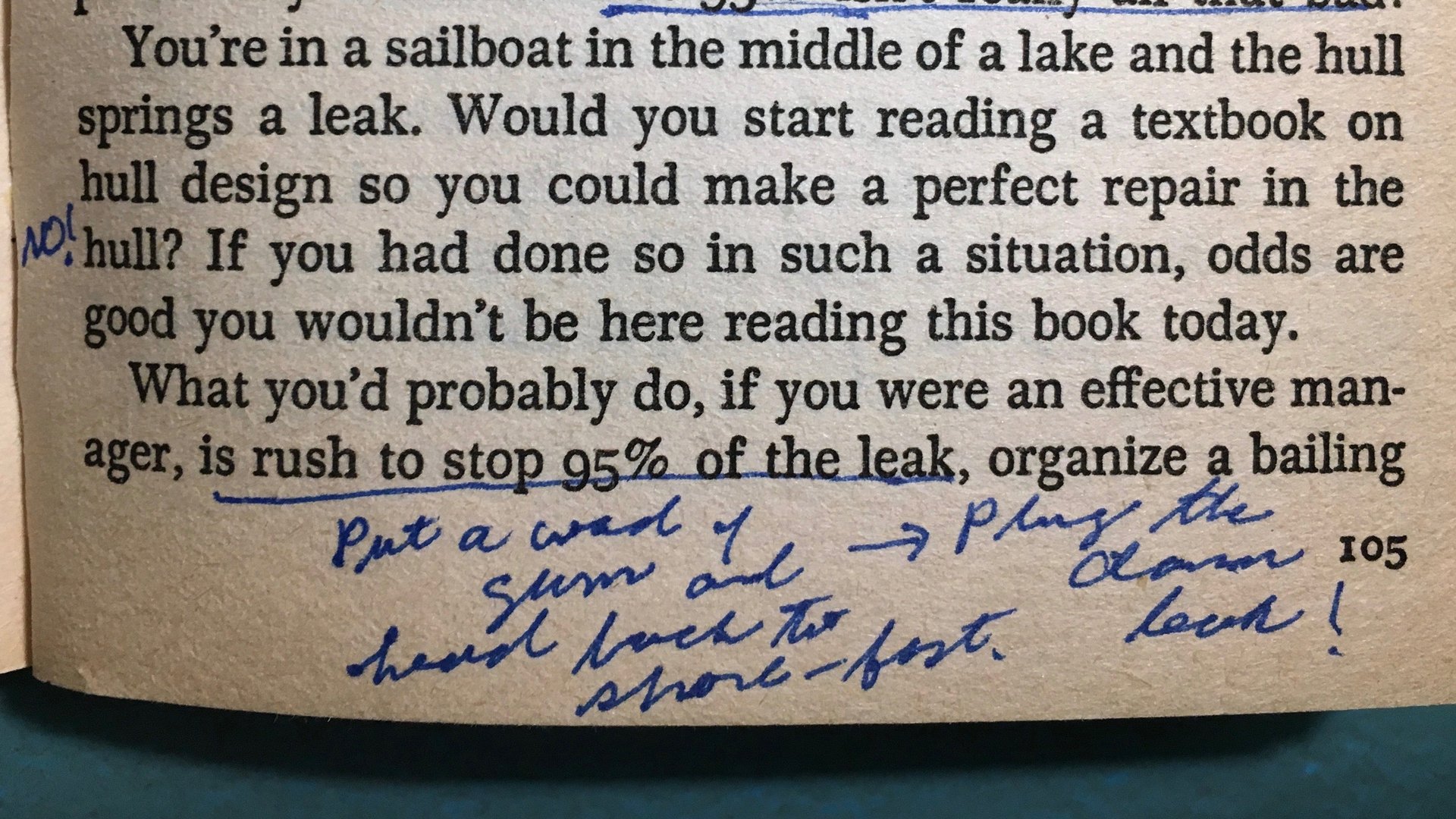

“You’re in a sailboat in the middle of a lake and the hull springs a leak. Would you start reading a textbook on hull design so you could make a perfect repair in the hull? [Reader: “NO!”] If you had done so in such a situation, odds are good you wouldn’t be here reading this book today.”

Sloma goes on to talk about how this is a metaphor for handling crises in an organization. Our reader got stuck on the boat metaphor and ended up writing a MacGyver-esque boat-repair plan in the margin instead, which ends up being about as good a piece of advice as any in the book.

“Put a wad of gum and head back to shore—fast,” the notes read. “Plug the damn leak!”

That the book so engaged its former owner probably would have pleased Sloma, who died in 2006. “As a business leader he was very interested in having people do their best,” his daughter Karen Sloma said. “He was bottom line-focused in terms of outcome but was interested in bringing out his team’s best talents, and if it wasn’t in a certain area he would mentor them into an area that would fit.”