A psychologist’s guide to speaking up against your industry’s Harvey Weinstein

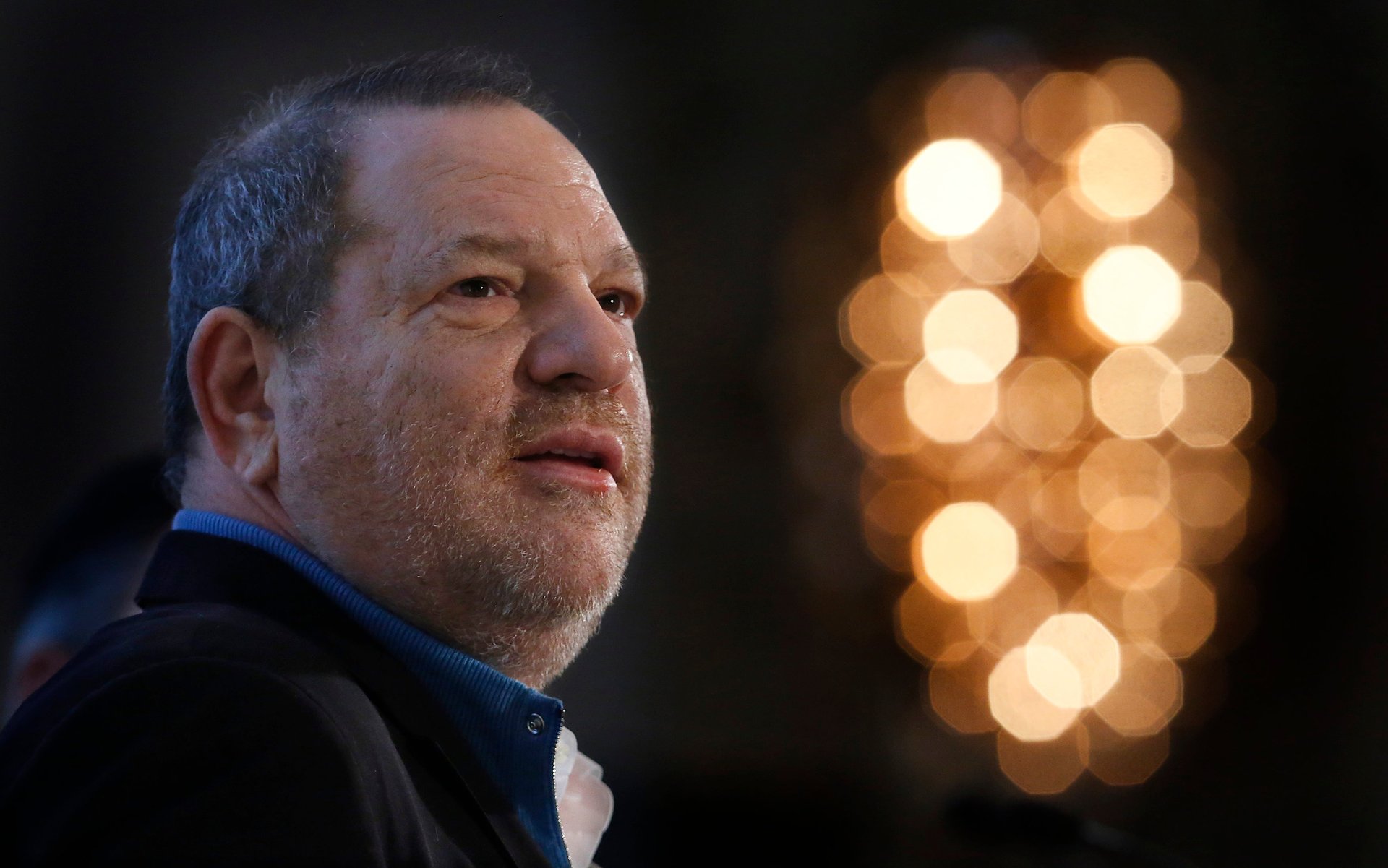

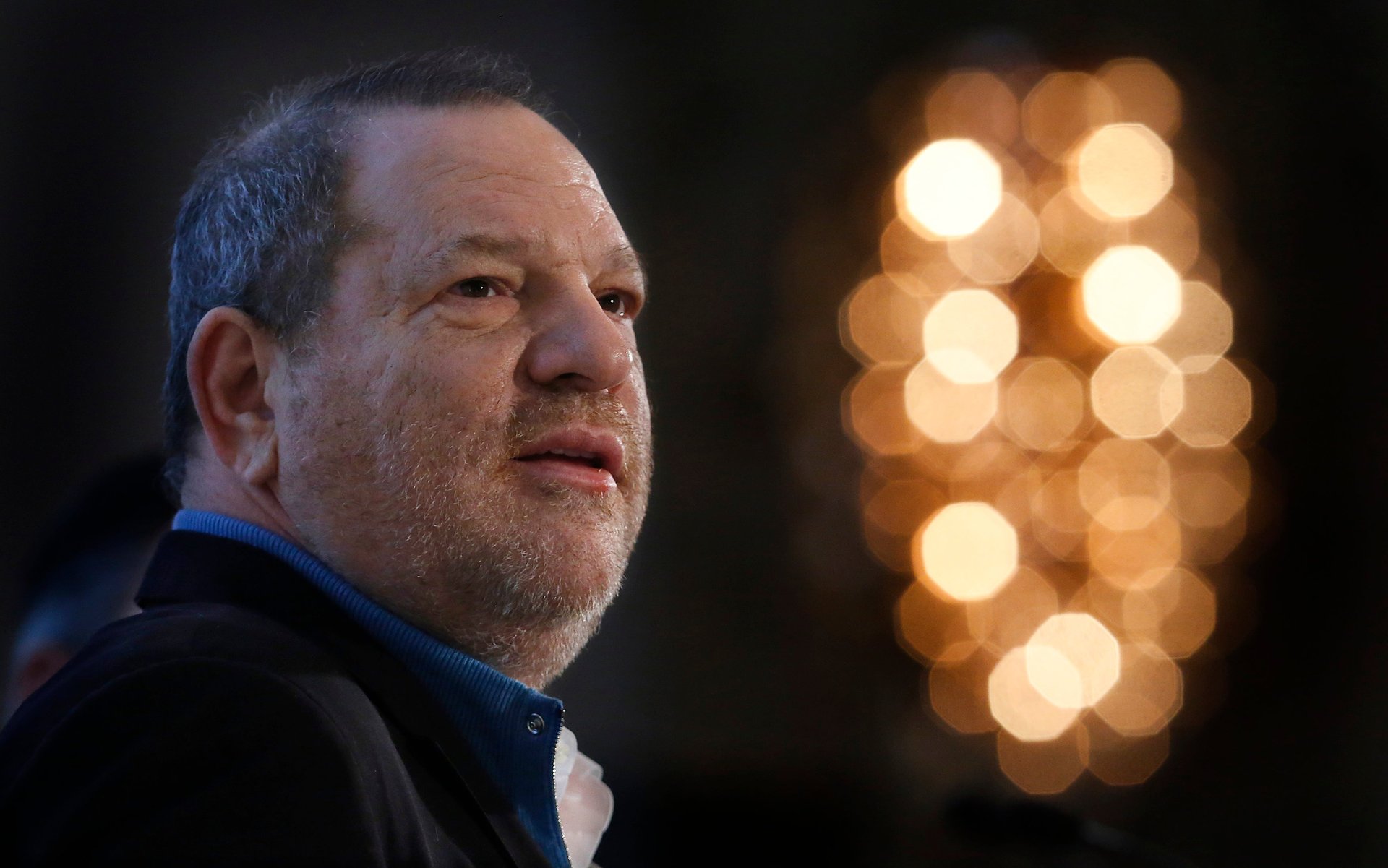

Over the past few days, the world learned that Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein has been sexually assaulting and harassing women for decades. Rumors of Weinstein’s horrendous behavior have apparently been circulating through the industry for years, with actors including Kate Winslet and Glenn Close acknowledging that they’d heard vague stories but dismissed them as gossip. Meanwhile, Weinstein continued to occupy an incredibly powerful position in the industry, victimizing seemingly countless women.

Over the past few days, the world learned that Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein has been sexually assaulting and harassing women for decades. Rumors of Weinstein’s horrendous behavior have apparently been circulating through the industry for years, with actors including Kate Winslet and Glenn Close acknowledging that they’d heard vague stories but dismissed them as gossip. Meanwhile, Weinstein continued to occupy an incredibly powerful position in the industry, victimizing seemingly countless women.

Acting on rumors runs contrary to everything we’re taught. Typically, our culture discourages us from passing on information if we have no direct evidence of wrongdoing, lest we wind up spreading malicious gossip. And when the alleged abuser is a powerful person in your field, it’s normal to worry about how speaking up could threaten your career prospects. But in the face of the high-profile cases of sexual harassment that have dominated the news cycle in 2017, it’s become increasingly clear that staying passive only perpetuates the cycle of abuse.

Victims of sexual harassment and assault already have to carry an enormous burden. It is unreasonable to expect every victim to come forward and protect everyone else. And so for anyone who cares about a creating a work environment that is safe and respectful for all people, it’s time to make a pledge to refuse to be a passive bystander. If you’re confronted with rumors about assault and harassment in your workplace, it’s absolutely necessary to listen, ask questions, and speak out.

First, take allegations of misconduct seriously. No matter how surprising or far-fetched you perceive a rumor to be, it’s important not to dismiss it out of hand. Whether the rumor is about sexual harassment or some other form of untoward behavior, you need to be clear that you take the claim seriously.

From the outset, be clear about how you intend to proceed. If the person in question is a victim, let them know whether you will keep the information confidential or whether you feel compelled to share their story. It’s possible that you can’t in good conscience stay silent, but you should say this upfront in case the person chooses not to share any further details with you. Should that be the case, any information you do share should protect their identity. Sharing information that was shared with you in confidence only further victimizes the person in question.

If the person in question is passing along secondhand information, you should also be direct about the fact that you are unwilling to dismiss stories of abuse without investigating further. Be assertive and say, “That’s a serious allegation. I can’t ignore that comment.” Ask if the person passing on the information is willing to connect you with the victim.

Next, ask open-ended questions to clarify the accusation. Broad questions leave room for substantive issues to emerge without suggesting that you’re taking sides one way or the other. You can ask things like, “How did the situation play out?” The more specific the description you receive, the better. You want to avoid subjective terms like “harassed” and get a clear picture of what actually transpired. The specifics will help you determine whether the incident needs to be reported internally or even go directly to the police.

As you become more confident that there was impropriety, provide support and encouragement to the victim. You can offer help by acting as a sounding board, by encouraging the person to take action, and by being physically present as they tell their stories. If the person is passing on someone else’s story, offer to talk with the victim or ask the intermediary to share your concern and support. Knowing there is at least one person who believes the story can make all the difference for someone trying to make sense of abuse.

Another important way to support victims of abusive behavior is to connect them with others who’ve had similar experiences. Victims often shoulder much of the blame for abusive incidents, believing that they didn’t do enough to stop the assault. Shame leads to isolation and people suffer in solitude while the perpetrator goes unchecked. This attitude is tragically apparent in the testimony of many of the women who talked with the New Yorker about their experiences with Weinstein. Actress Asia Argento, who says she was sexually assaulted by Weinstein, told the magazine, “The thing with being a victim is I felt responsible,” she said. “Because, if I were a strong woman, I would have kicked him in the balls and run away. But I didn’t. And so I felt responsible.”

But once victims learn that others experienced very similar abuse, their shame is lessened. And their resolve to stop more attacks grows. If you hear similar complaints from different people, offer to connect them.

Regardless of whether you’ve heard one complaint or twenty, report abuse through the formal channels of your organization. Ideally, it will be the victim reporting the incident, but if the victim is unwilling to do anything, you should report the case yourself. Most organizations have a Human Resources department that is responsible for employee safety. Decide whether it makes sense to make the complaint in person or whether you are better to maintain anonymity. But either way, it’s important to report concerns to increase vigilance and create a paper trail. Even if you’re dealing with secondhand information, it is important for HR to know that there might be something wrong.

In some cases, the HR department might not act on the information. They might feel that evidence is insufficient to warrant a formal investigation, or they might fail in their obligation to employees because of fear of repercussions for their own careers. If HR fails to act, you’re left with the option of raising the issue to other powerful people in the organization. Simply ask what they would have you do. You could say, “I have evidence of sexual misconduct on the part of a senior person in our organization. I reported it to Human Resources and have seen no evidence that the issue is being addressed. What would you advise me to do?” Again, you have the option of communicating anonymously (for example, by creating an anonymous email account or by sending an unsigned letter) until you have confidence that your concerns will be handled appropriately and that victims will be protected.

As you work through the appropriate channels, you can also do a lot to warn your colleagues about the danger of certain situations. You can also provide cover for one another and reduce the number of situations where your colleagues are vulnerable. For example, ensure that no one will stay in the office alone with the abuser. Arrange to have at least one other person present at all times. Preventing isolation is especially important outside of the office and on business travel, where colleagues can help shield each other by coming and going in pairs.

Bullying, whether it’s sexual or not, is about power. It’s incredibly difficult to counter the power imbalance while you are being bullied. It’s much easier to disrupt the unhealthy dynamic when you are a bystander than when you’re the victim of the abuse. That’s why you need to act on allegations when you hear them. You might be in the best position to stop another person from becoming a victim.

Unfortunately, in the case of Harvey Weinstein, very few people chose to say and do the things that could stop the cycle of predation. We are fortunate that journalists were willing to shed light on decades of abuse. And with Harvey Weinstein, Roger Ailes, and Bill O’Reilly all ousted from their jobs once their abuse of power became public, perhaps more men and women in the future will understand that amplifying rumors of assault is worth the risk.