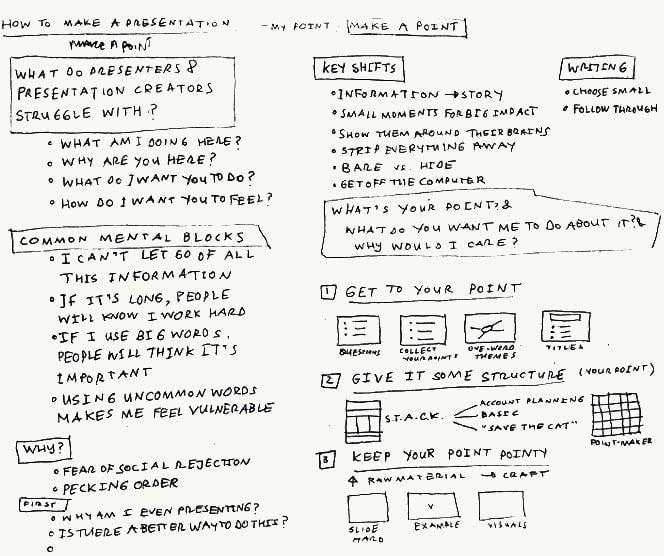

You only need to do three things to make a great presentation

You’re in front of a group of people. Your jaw juts and words poke out almost by themselves. The room seems glazed. Its den of eyes stare out, but are turned off from the inside. CLICK. You make the next slide appear. It thumps to arrival. The eyes don’t stir.

You’re in front of a group of people. Your jaw juts and words poke out almost by themselves. The room seems glazed. Its den of eyes stare out, but are turned off from the inside. CLICK. You make the next slide appear. It thumps to arrival. The eyes don’t stir.

You turn to the presentation. The numbers, sources, and bullet points stare back. Nervous you might forget something that will utterly convince the eyes to return to your allotted time of thirty-minutes-plus-five-minutes-for-questions, you read aloud one hundred words. Thirty seconds pass. You find your back to the room, and you remember that the presentation class said, “Don’t turn your back to the room.”

You catch your mistake and you spin around like a belle at a ball. The G-force knocks your thoughts from your skull. You jut your jaw. No words poke out. Your cheeks fizz, your throat dries, your breath halts. This moment was going to make you. Then, to bring yourself back to earth, you wonder, “Why am I here again?”

Great question.

“Why am I here again?”

Humans are blessed and cursed with the ability to ask this question. Where other animals are free to animal, this question tickles and shin-kicks human brains day in, day out. Answers have led to art, war, love, hate, articles for business websites, and cumbersome presentations. If you’ve ever frozen in front of a presentation, remember, you’re here to do three things:

- Make a point

- Make people care about your point

- Ask for something

We’ll focus on your point—how to get to it, how to structure it, and how to design it.

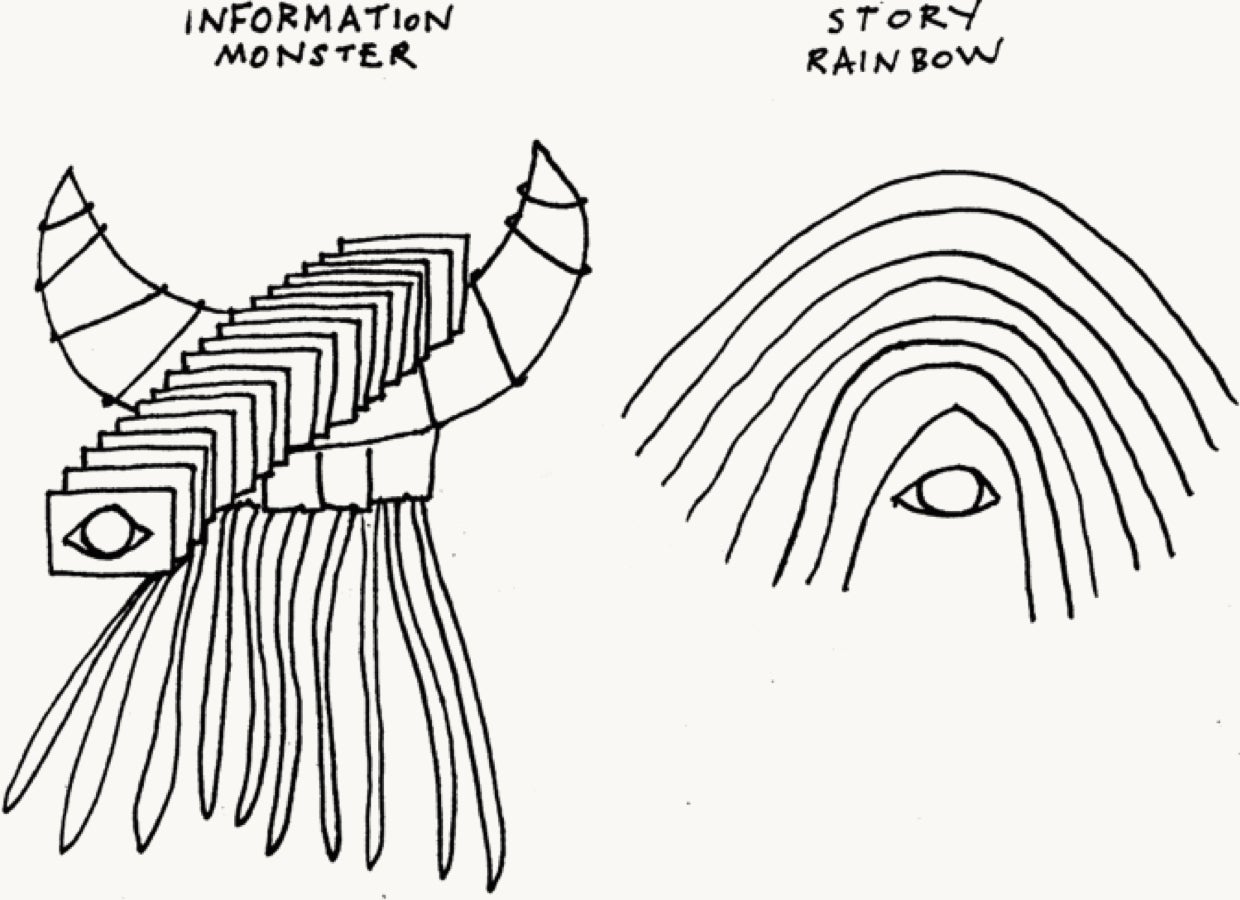

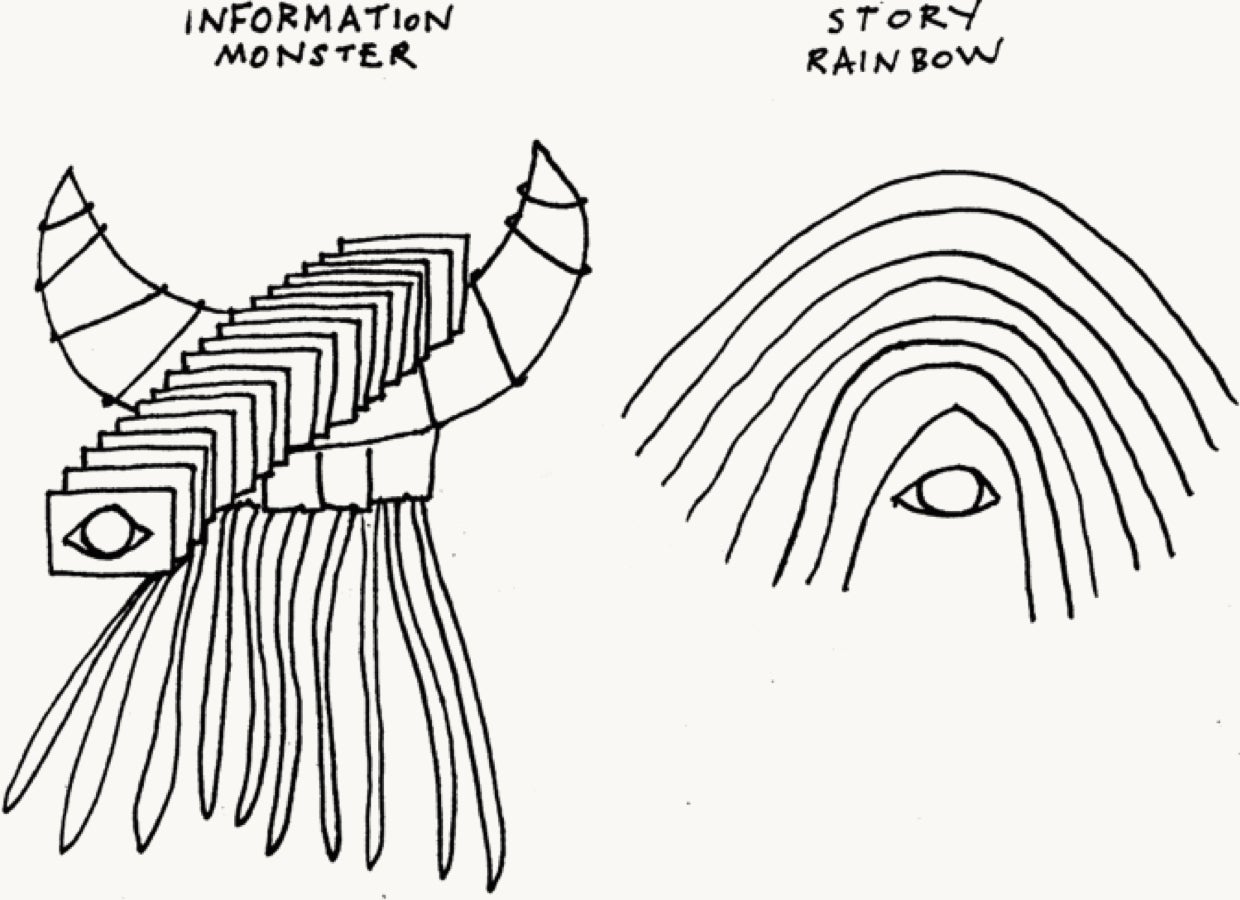

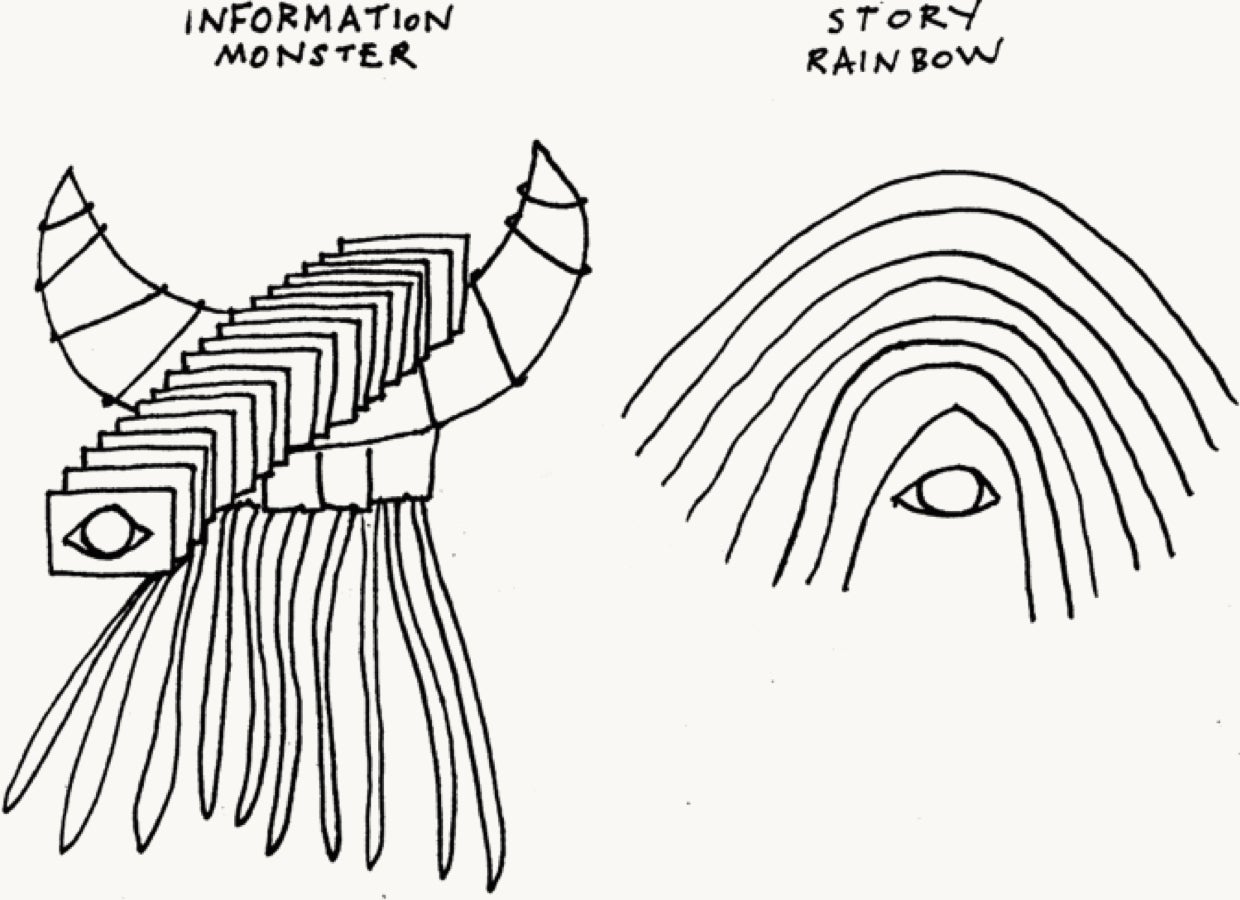

First: Aim for story rainbows, not information monsters

Many presentations feel like leafing through a collection of index cards in an old library catalog.

A, B, C, D, E, F, G.

Agenda, Overview, Objectives, Research, Competitors, Strategy, Metrics.

- Bullet point

- Bullet point

- Bullet point

Information matters, and bullet points have a place. However, you only need to look 2017 in the face to know that you can’t always inform your way to change.

Presentations like this are what I call “information monsters.” They are big, long, huge, and overwhelming. One hundred slides and no point makes people want to hide under the bed until you’re gone.

“Story rainbows,” on the other hand, are presentations that captivate instead of try to subdue. They have a main, just-left-of-center point, and they re-assemble all the information around this main point. “Story Rainbows” travel infinity, whereas “Information Monsters” get stuck on company networks and lurk there infinity.

So keep the story rainbow in mind as we go through the mechanics of making presentations make a point.

How to make your point

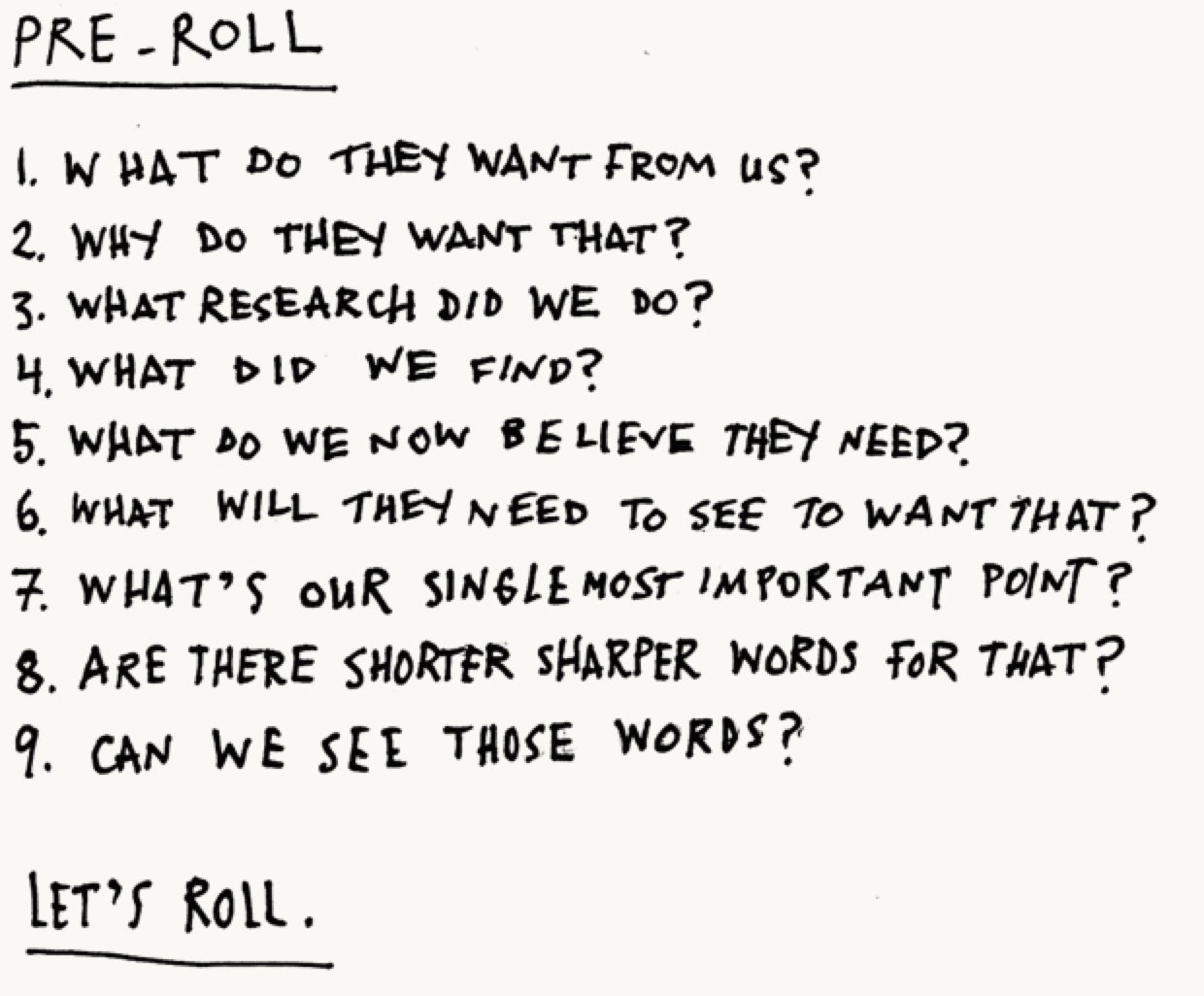

Start by asking questions: This is a set of questions to keep handy at all times. These questions will help you bridge what your audience asked for (or what you would expect them to ask for) and what you think they need, now that you’ve done the research.

Do a point dump: Take a piece of paper and, as you work through the information, capture key points. Even if you need to use long words in the presentation, try to use short words on paper. This is how I started work on this article.

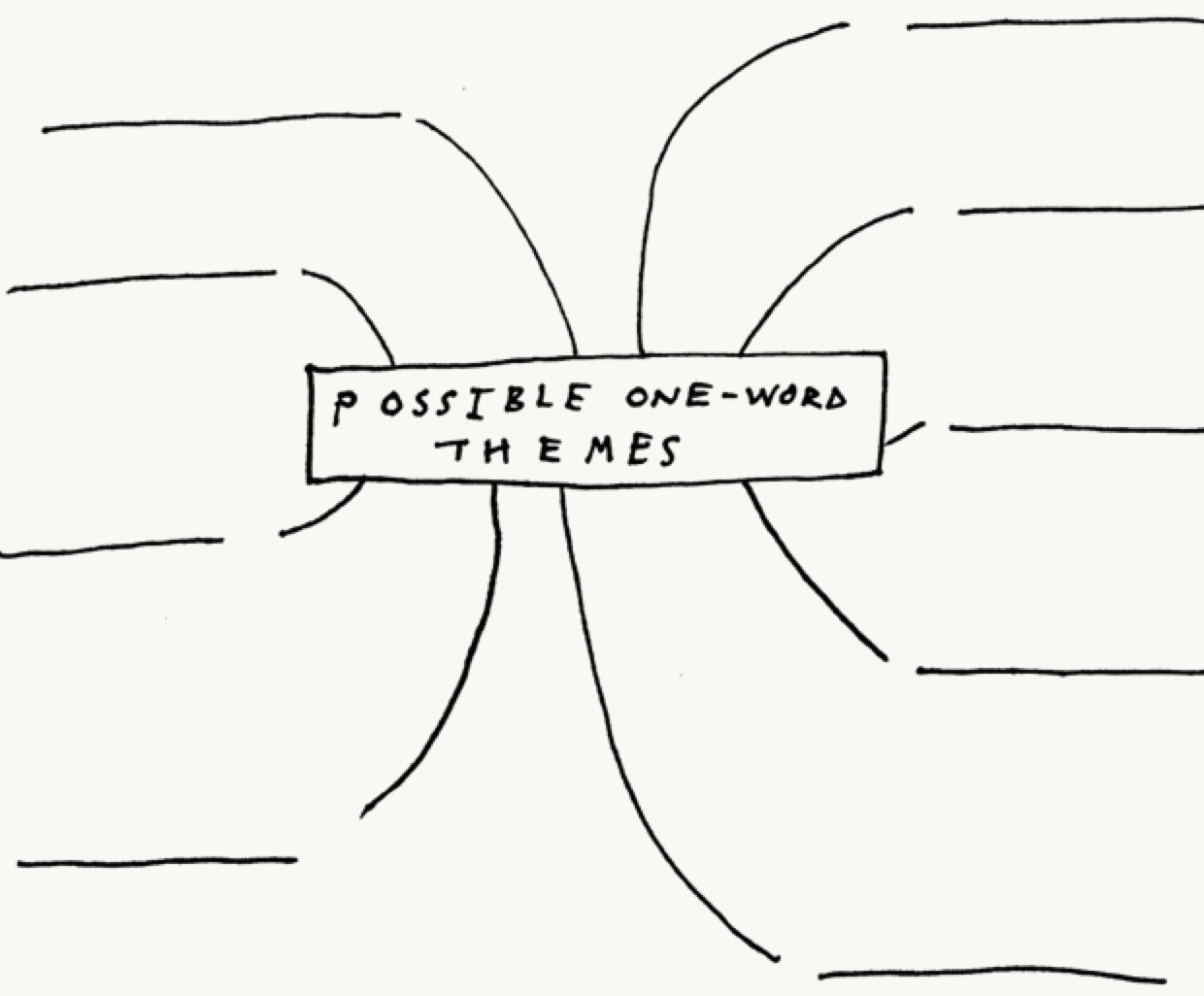

Find the words: All creative work tends to go through divergent (exploring lots of stuff) and convergent (narrowing and focusing) phases. Having dumped your points on paper, play this game on your brain: think about the one short word that best summarizes your point. Then think of others and mind map them (or list them). Feel for words that don’t seem too obvious and common. For this article, “pointy” is a word I like. I also like puns and dad jokes.

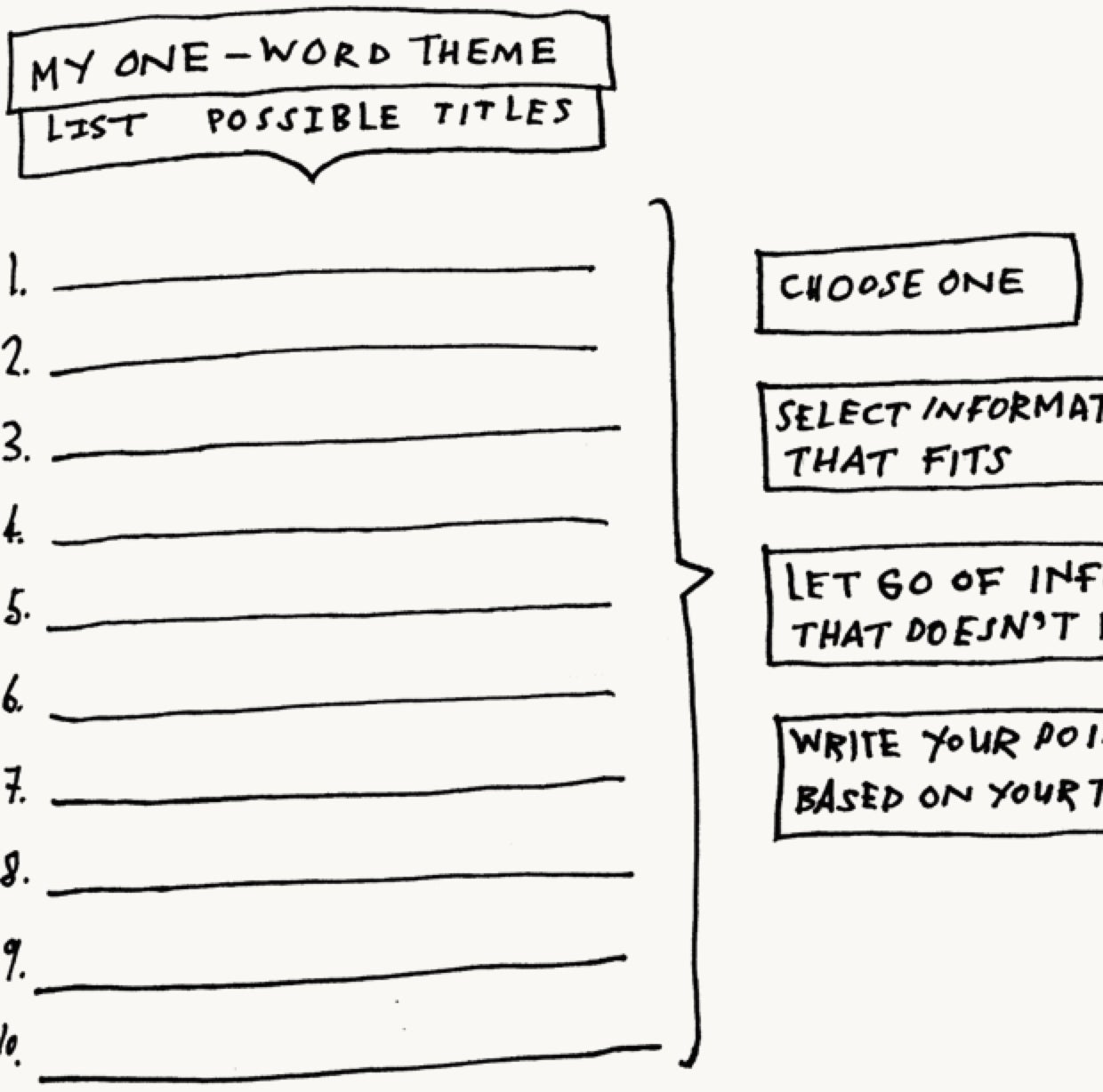

Workshop titles: You might have farmed a few fine words from the previous exercise. Choose one and then list possible titles. You can do this on paper or take notes on your phone throughout the day as your sub-conscience kicks in. This is a good time to take a walk. It’s also a time to get your brain into an arm-wrestle—move it back and forth between words, seek less common language, push everything shorter and sharper. You’ll often need to use a mental keyword (“presentation” is the mental keyword in this article) but nudge something less common into it or use a common word in an uncommon way.

Three examples for this article:

- How To Make A Presentation (the starting point but not specific enough)

- How To Make A Presentation Make A Point (using “make” in concrete and figurative ways)

- How To Make A Pointy Presentation (a shorter and less obvious version of 2.)

You can settle on a title now or keep a couple alive. The real challenge is re-visiting your information monster with your word and title in mind, knowing you’ll have to do three things:

- Select the information that fits

- Let go of information that does not fit

- Re-write your points based on your word and title

The presentation plan

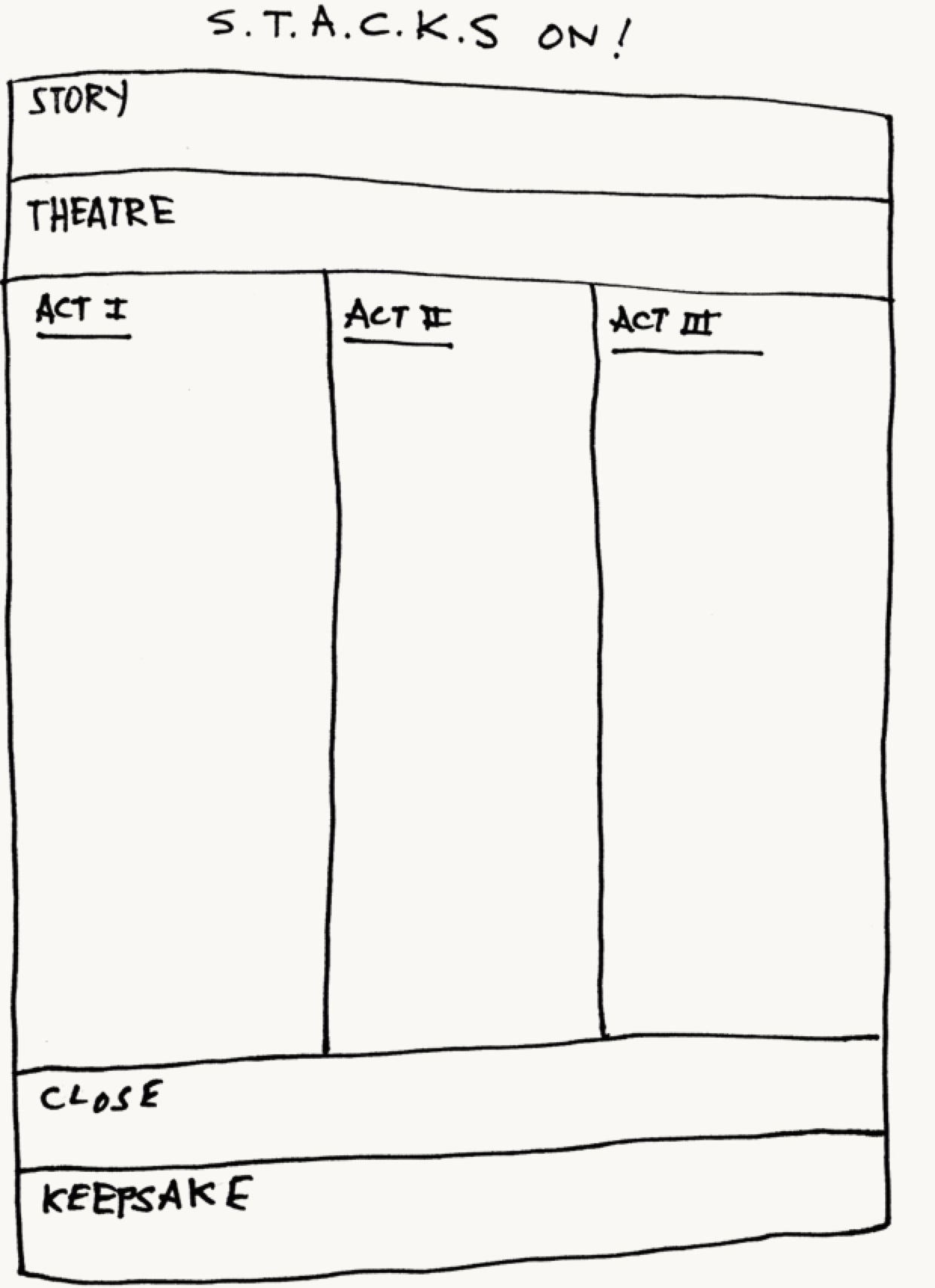

Stories tend to have three acts. As I plan my presentation, I plot them out, like this:

Story: What’s the Single Most Important Thing (S.M.I.T.) you want people to take from this presentation? Here, use your words from before. For this article, I want you to know there are practical ways to make a presentation make more of an impact.

Theatre: What’s a provocative way to bring my point to life? In this TEDx talk (The World Would Be Less Strange If We Stopped Making Strangers Out Of Men), I wanted to talk about how little we know men and how hard it is to be vulnerable. My theatre was two-fold: first, I didn’t use a presentation because I didn’t want to hide, and, second, I wore a shirt that I bought on the way to my grandfather’s funeral. I ended with a story about being with him when he passed away and what another man said to me at his funeral.

Act I/II/III: When you hear someone say that a good presentation has a beginning, a middle, and an end, this is what they are talking about. It’s borrowed from screenwriting.

Act I tends to start with the regular routine and happens in the “real world,” which is the current status quo. It also tends to start with an opening image. Think of this as your hook. How will you poke people in the brain to get them to pay attention? Common business examples include:

- A provocative question (“When’s the last time you made a presentation that made a point?”)

- A statistic (“Did you know that 99% of presentations don’t make a point?”)

- A small moment (“So I was sitting in a room and could see someone’s mouth moving…”)

Act II breaks the routine and happens in the “other world,” the one that is possible with the solution that you’re presenting. It often ends with a Long Dark Night (almost beaten and ruminating, the hero collects herself and returns for Act III). In a business presentation, a Long Dark Night might be a “What If We Don’t Do This?” provocation.

Act III returns to some kind of routine in the “real world.” It tends to finish with a closing image that is the opposite of the opening image. Writers also call this follow-through—when you mention an idea or anecdote early and then re-frame it later. Two examples for this article:

- We conclude by mimicking Oprah and we say, “Now you get a point. You get a point. You get a point. You get a point. Look under your chairs, the presentation is there.”

- We bring in a balloon fish and ask everyone to poke it so they can see how pointy it gets (if we did this we could even start with a story about a balloon fish)

A fall-back structure for advertising presentations is no more complicated than:

- Scene-setting: What We Did and What We Found (research, audience definition, problem definition, competitive analysis)

- Rising action: What We’ll Do About It (brand strategy, ideas, manifestos, channels, communications plan)

- Denouement: How We’ll Do It And Make It Work (team, process, metrics, budget)

Close: How can you make your point end strong? You may like to summarize the three key things you discussed, but don’t then turn to a slide that says, “Thanks.” You can get the group of people to do something, you can finish with a small story, or you might play video of an interview you conducted. End, don’t disappear.

Keepsake: What can you leave behind to keep the point alive? A typical leave-behind is a printed, bound version of your presentation. Cool. Swag is also common. Leaving behind a balloon fish aquarium? Now that’s a keepsake.

Keep your point pointy

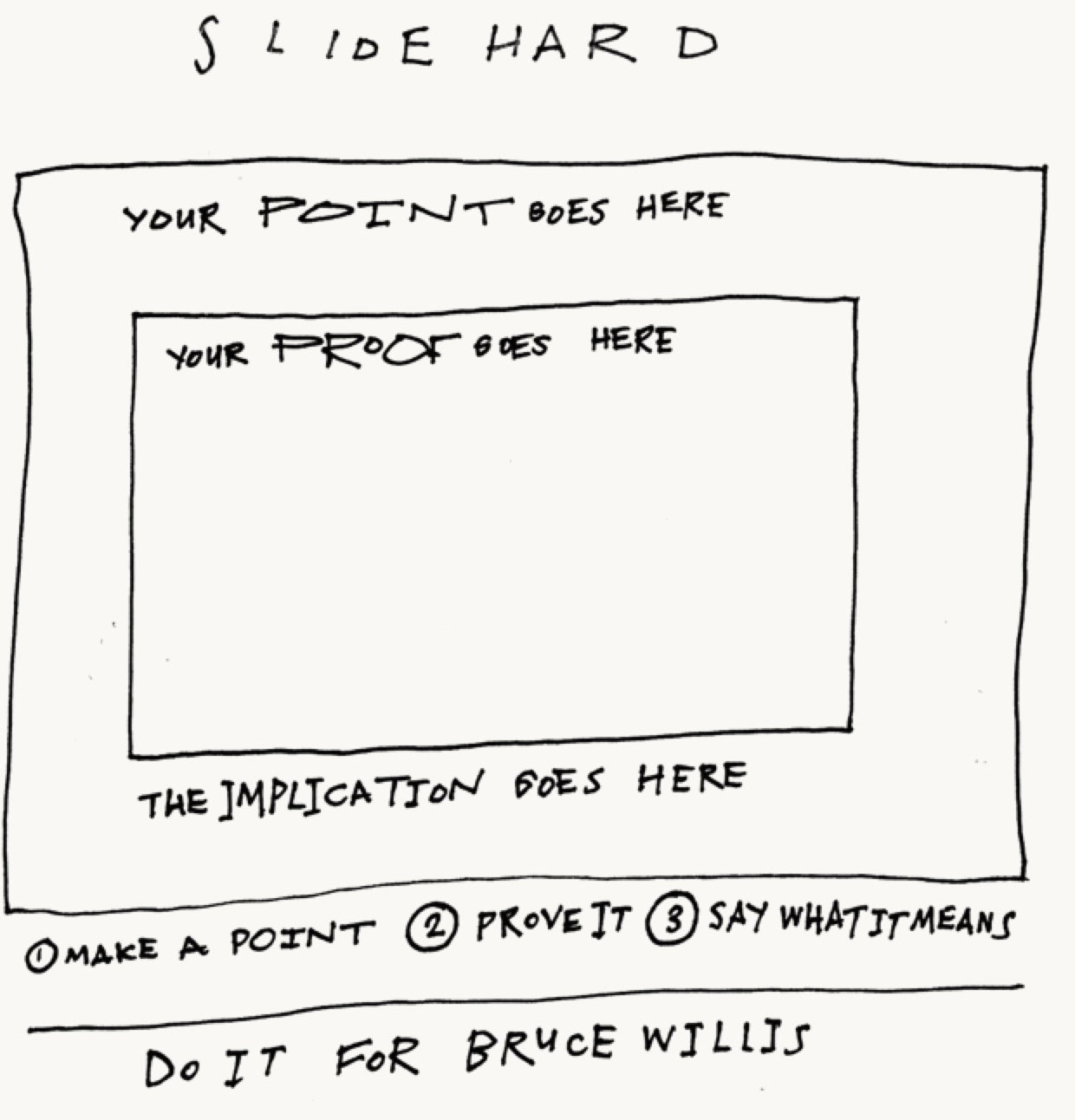

Slides: If you work with conventional slides, take everything from above and start laying them out. Just keep in mind that you want each slide to work hard (or delete it) and slides work hard when they:

- Make a point

- Prove a point

- Help people understand what to do about the point

This isn’t dogma but a basic slide layout might look like this:

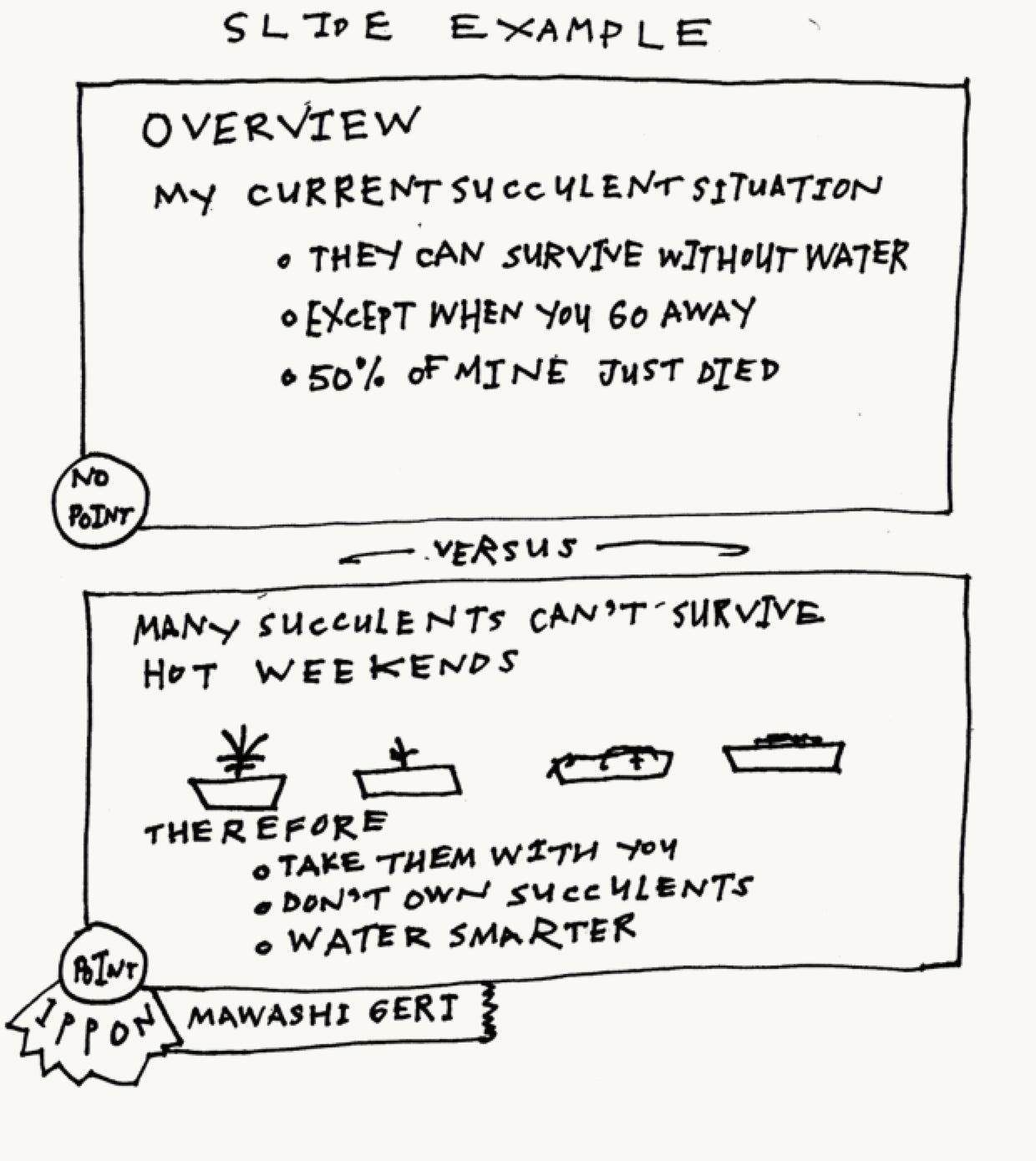

And it might read like this:

Happy endings

All of my points here are just a bunch of ideas and tools. You have your journey to take. You have more control over how you approach a presentation than its outcome. You have more control over how you practice presentation skills than how a presentation is received. It is all an experiment.

But if you can look into the bathroom mirror of Floor 21 of that downtown building and have a clear, visceral answer to the question “What am I doing here?” then others will want to be Here and wherever Here goes with you.

Stay pointy, my friends. We’re all Story Rainbows on the inside.

This article is part of a Quartz series on how to make “pointy” presentations.

Mark Pollard is the CEO at Mighty Jungle, a brand strategy agency in New York.