Lean Startup evangelist Eric Ries on how big companies can stay competitive

If you’ve ever used the word pivot in a meeting, chances are you’re putting into practice an idea from Eric Ries’ The Lean Startup.

If you’ve ever used the word pivot in a meeting, chances are you’re putting into practice an idea from Eric Ries’ The Lean Startup.

The book, written in 2011, combined Ries’ experience as an entrepreneur with concepts from lean manufacturing, agile software development, and the theory of constraints, creating a playbook for startups to launch products quickly and efficiently. The book birthed the buzzword MVP, or minimum viable product, as in the “smallest version of a product you can use to start the process of learning from customers.”

Ries had initially set out to write a “general purpose theory of entrepreneurship.” He didn’t expect the Lean Startup idea to spread globally, with meet-ups across 94 cities in 17 countries. And he certainly didn’t expect its principles to resonate with what’s become a powerful and unlikely audience for him: managers and executives at the world’s largest companies.

Ries’ new book, The Startup Way (published in October), addresses this audience more directly in some respects, offering a framework for cultivating and codifying an entrepreneurial mindset at companies of all sizes. Ries recently sat down with Quartz At Work to talk about innovation “blockers”, incentive systems, and reimagined org charts for businesses at any stage of development. This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Quartz At Work: Can you walk us through what happened between the completion of The Lean Startup and your writing The Startup Way?

Eric Ries: The first book raised a lot more questions than it answered because I was really focused on a very specific use case. I thought I was writing a general purpose theory of entrepreneurship, but I hadn’t actually used it that widely myself. I was doing my best to show from an intellectual point of view how I thought it could be used more widely. But I didn’t really know that GE would try to use it to build diesel engines; I didn’t expect auto manufacturers to pick it up as a rallying cry; I certainly didn’t expect it to see it adopted across financial services, and I had the vaguest inkling that city, state, and federal governments [would cite it]. I could never have imagined all these different people rallying under the same banner.

With these bigger institutions and companies, was there some component of The Lean Startup that really spoke to them?

Well, I’ll be really honest—there’s a bit of Silicon Valley envy and a bit of Silicon Valley fatigue at the same time. We can have an arrogance problem, you might say. There’s a fascination with the idea that technology can change the world, but also it can be relatively inaccessible to most people who find our jargon, not to mention our lack of inclusion and many other faults, off-putting. So I think that building some common language and bringing some intellectual rigor to the practices made it more acceptable.

This was a surprise to me but so many general managers I have met in the last five years find that it speaks to them. They think of themselves as entrepreneurs more than I realized. They’d read the stories in the book and say, “Oh that’s me, I’m just like that guy,” even though the surface characteristics are different.

There was a guy in Louisville—if you met him, you wouldn’t say, “Wow, Silicon Valley innovator.” If you looked at his resume you wouldn’t say, “Ooh this is a very creative, risk-taking person.” He works at a big company, he works on a big product line that’s super boring. But he’s a very entrepreneurial person, he’s always wanted to push his organizations where he’s worked and do things in an innovative way. But traditional management practices kind of pushed him underground and forced him to hide that side of himself.

So there’s this underground network of innovators who are dying to bring their creativity to work, their passion and vision to their job, and they’re not able to because we’ve built systems around them that make it impossible. This guy in particular, he started doing a Lean Startup project in his company—because the company was embracing Lean Startup—he immediately ran into political problems with various middle managers who didn’t like that he was doing things differently. And even though the company was in the middle of this transformation, he himself had to take his project underground and hide it for a while. It reappeared later, after he had enough progress and success. I kept seeing that over and over again; it’s been really eye opening for me.

What are the blockers of the entrepreneurial mindset in larger companies?

If you look at a systems level of how we hold people accountable, the incentives used, they’re horrible. At most organizations, if you’re perceived to have failed at anything, that’s a major career liability.

An important concept in the book is “career equity.” The true compensation a person has in an organization is not the cash and bonus you pay them right now, but their perception of future career prospects. If they think that doing something that is perceived as a failure will prevent them from being able to get promoted to the job that they’ve always wanted, to get promoted to a level where they can have control over their [work] plus all the rewards that come with being at the top of an organization, then of course people aren’t going to do it.

You see that in how teams are funded. I talk about the “entitlement funding” system at companies where we treat funding like an annual appropriation, versus the “metered funding” approach we use with staged rounds in Silicon Valley. We have people working in functional silos and handing off work across siloed boundaries, instead of building a cross-functional team. Those are all positive consequences of a really good 20th-century management system that was amazing for what it was trying to do, it was just built for a different time.

What is so unique about this time that is requiring the change you prescribe?

Compared to any decade you pick of the 20th century, but certainly compared to the decades where most of the management systems we use today were invented, it’s different now. From the time General Motors had product-market fit with one really good idea that Alfred Sloan put together in the 1920s, to the time it that it ceased being the No. 1 automaker in the world—what was that, 80 years?—that’s a long time to be No. 1 on the strength of basically one really good idea.

Today, by the time a startup reaches product-market fit it will have 25 competitors. Certainly by the time a company goes public, it’s gonna be copied and replicated, not just domestically, but globally. The moats and barriers to entry that protected incumbent businesses in the past were just so much stronger across the board than they are today, in part because of digital technology but also because of other trends like globalization.

So, the management portfolio is being shifted involuntarily, and sometimes because we want new growth, we do it on purpose, but for most companies it’s shifted in the direction of needing higher beta outcomes. So that means projects with more uncertainty. The traditional management tools are horrible in that part of the portfolio and so we have to develop tools that are designed to handle that situation.

How do incentive systems need to change to accommodate this new way of working?

Yeah, that’s a big topic and I’ll try to give a few examples as I don’t mean this to be a comprehensive answer because the details matter a lot. The general theme is to look at the leading indicators of future success rather than the trailing indicators of past good decisions. I was just with a mass production-oriented company and there, if you have a good idea, maybe you test it out in a test market, decide it’s a good idea, ramp up production, build up a lot of supply, launch it in all of your markets with a big PR push and hold the team accountable for how much sales they get per period on this crazy growth curve. And that really doesn’t work well if there’s any uncertainty whether customers want the product or not, because how do you make the accountability plan?

The team is asked to make a forecast, by definition it’s going to be a hockey stick growth curve. During the flat part of the hockey stick we don’t have enough data, the numbers are too small to matter so we can’t hold anyone accountable. Once the launch happens and the plan says we’re supposed to sell 3 mm units. Where did that number come from? How do we know that that’s accurate? What if we sold 2 mm units, is that a success or a failure?

In the tech industry we learned the hard way that sometimes having 10,000 passionate fans and if you launch a product where 10,000 people absolutely adore it, that’s going to be better than having a million people who tried it once and said “eh this sucks.” So we have to start to learn what the leading indicators are, the per customer metrics of success, and then ramp up in proportion to the learning progress that we’re making. That’s a Lean Startup lesson.

When you think about how companies institutionalize that at as compensation or promotion practice, it’s really bad. Especially because some managers have figured out that if you can get promoted during the time that your project is in the flat part of the hockey stick, then you’ll never really face accountability. And it will be your successor’s problem when the product finally launches. And therefore you have a tremendous incentive to build projects that are big enough and can justify the long flat part of the hockey stick, put off accountability into the far future so that we have plenty of time to get promoted. And then companies wonder how come we never launch anything, how come all of our projects are so slow. Well you’ve created an incentive system that dramatically rewards delay over action.

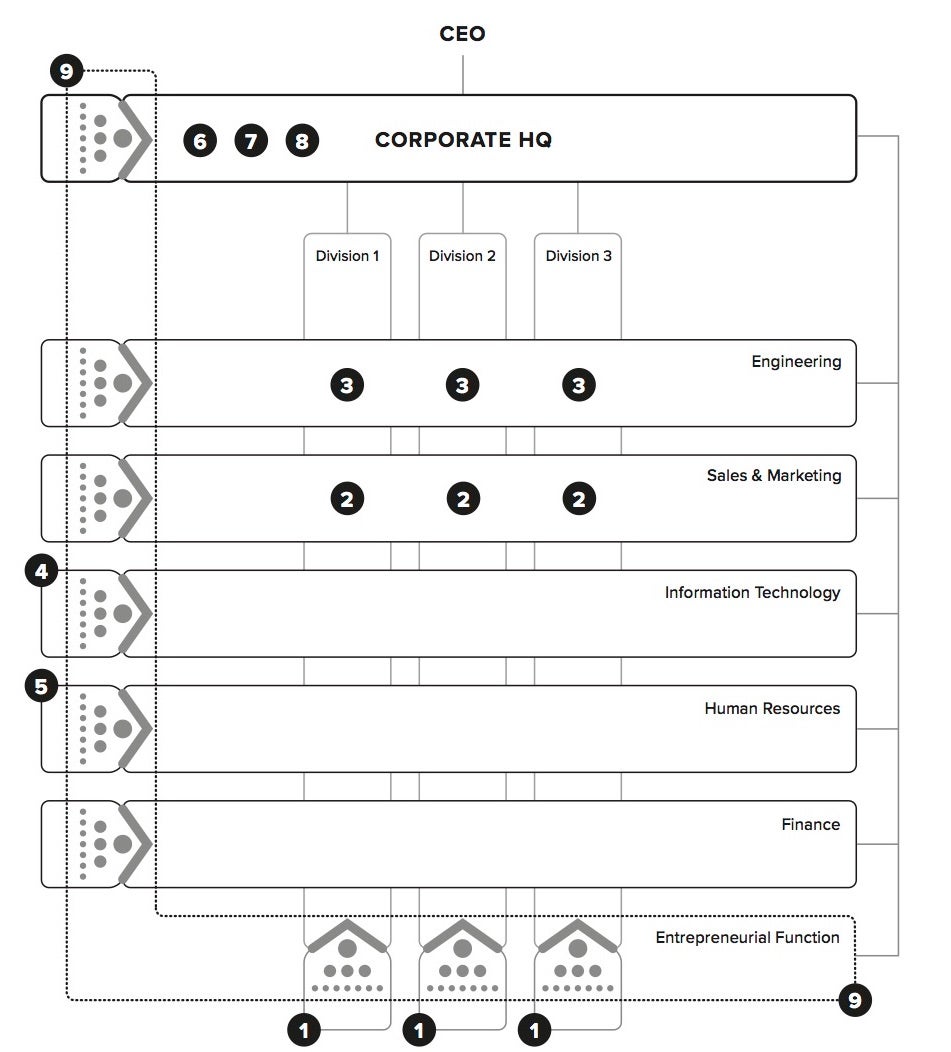

How does the organizational structure have to change to accommodate this type of thinking? I saw in the book The Startup Way that it involves this square diagram with a lot of columns…

I get a lot of flack for it because some people think that if we’re going to be more innovative we need to get rid of structure, and not have an org chart, and not have reporting hierarchies, and not have functions anymore, it’s like we’re going to blow up the system to save it.

And I haven’t seen the evidence that this works; nor have I seen any evidence that you need to do that in order to foster innovation. The big clue that’s hiding in plain sight is that that’s not how Silicon Valley works. People see the way that we work and see the diversity of the different kinds of company cultures we can build in all these crazy startups, and they see the freedom that we give to entrepreneurs to try new things and they just assume that our process is relatively unstructured. But in fact Silicon Valley operates by a very strict management system that’s highly consistent from company to company and yet we don’t ever talk about it because it’s so obvious that we would do it that way. Every startup has a board, a composition of a variety of insiders, investors, and outsiders. The certain way we do board meetings and report progress. There’s variation on the themes, but the rules are pretty specific.

If we’re going to ask ourselves, what’s the right structure for a company to support internal startups. The startup is like a tool in your toolkit. If you find yourself with a highly uncertain management problem “throw a startup on it.” It’s what Amazon calls a 2 pizza team. If you’re going to have startups running around your organization, who the hell is going to manage them, where do they live in the org chart? For sure, Alfred Sloan was not thinking about this! The conventional org chart has no home in this kind of activity. There’s no function with responsibility for entrepreneurship. So that’s the first insight, we need to find a home for the activities in these org charts, call it something and say who’s in charge.

Most CEOs when I say “who’s in charge of entrepreneurship, they say “everyone is” and everyone is supposed to be innovative. Can you imagine if we put that up for marketing or finance. “We don’t need a CMO, everyone’s in charge of marketing.” No way.

But then a lot of the answers that people give about how to manage innovation, if you transpose them to different functions are laughable. Can you imagine if we had a finance lab? Finance is both a distinct function and woven into the very fabric of the organization because it oversees certain activities that all the other functions and divisions do.

So why is entrepreneurship really any different? So we have a missing function, let’s add entrepreneurship to the org chart. That causes another problem, which is how are we going to change the org chart from the one we have today to the one that works in this entrepreneurial way. It instantly creates a transformation problem where we effectively have to “found” the company all over again.

When you create these entrepreneurial units, do you pull people out of their existing teams? Or do they start to wear two hats?

There is absolutely no evidence in the literature that multitasking is a good idea or in any way effective. Yet we’re totally addicted to it, it’s like the fast food of management science.

I’d rather have a 5 person team, 100% dedicated, than a 25 person team 50% dedicated. And in Silicon Valley one of our most cherished beliefs is that small teams beat big teams, yet when our companies grow up they build these huge teams.

You call these new teams semi-autonomous. What does that mean in practice?

Semi-autonomous only means that once you’ve agreed on a shared mandate with that team, then they’re free to operate by whatever means necessary within those parameters that you pre-agree. You give them a fixed budget and say “spend the money on whatever you want” but don’t come asking for more unless you have (in Lean Startup jargon) “validated learning” – you’ve figured out that you’re making progress.

Do you have any advice for managers on how they can espouse this type of thinking?

[There’s a story of] a pretty senior exec doing an internal Lean Startup project. We had taught his team to have a “pivot or persevere” meeting on a regular cadence. And the two most important questions we teach the leaders to ask is:

What did you learn? How do you know? It’s a collaborative exercise to figure out what is the truth and for the leader to probe a bit to see if this story is really grounded in facts.

Over the course of several meetings he noticed that his team was not having the meetings with customers that they said they would. Finally he said “Guys, what did you learn here? Tell it to me straight up, no bullshit, I won’t get mad just tell me the truth.”

And of course they said “Well actually boss, we realized that nobody wants to buy this product and we’re a little too embarrassed to admit it, so we kept trying again, and again, and again.” They discovered that the basic attributes to the customer on efficiency and performance were not important at all and (…) once they found that out, they were able to pivot and come up with a product concept that really work.

Over the course of several months he really viewed this as a breakthrough situation where he learned something he never learned before, his team was willing to consider new ideas, and he saved the company a ton of money and he found a whole new source of growth for the company because they actually built a product that customers like.

That’s just a prelude for the next thing that happened. Next call up was a [check-in] with a regional sales manager for a new product.

“I got bad news we didn’t make our sales quota for this product, we tried hard but we failed.” As soon as he heard that he said, “I know what to do. I’m going to take this guy’s head off.” That’s the manager playbook and basically start yelling at him saying “Try harder, what the fuck is wrong with you?” He had this instinct to do that. What would happen if I treated this meeting like the one I just hung up with and do it differently, just to experiment.“Ok (regional sales manager), what did you learn?” And there was a full sixty second pause on the phone and the guy couldn’t believe he wasn’t yelling. And after he recovered his composure: “Ok actually, this go-to market strategy really worked great in the US but here there’s an indigenous competitor that’s pretty good and the plan is not working because the market conditions are different.” He started to probe, ask some questions and came back from the meeting convinced that they had made a go-to-market mistake and now they could pivot that project and do it differently.

He said, “I would never have been able to discover that if I hadn’t learned to ask different questions.” And that’s actually when he became a convert to this way of working. When he started to apply these principles personally and ask these different questions, he started to see resonance across his work and with lots of people and lots of different teams.

For leaders, I would tell them, “Always look in the mirror first, ask yourself, ‘how are you holding the people you work for accountable, can you start asking different questions?’” That can be very personally impactful.

One of the lessons of the scientific method going back hundreds of years [is that] reframing a question away from success and failure—and towards “what can I learn?”—allows us to be dispassionate in situations that are highly charged. That shouldn’t be a new insight, yet we forget it all the time.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that The Lean Startup was written in 2001. It was written in 2011.