Why signing a noncompete agreement is bad for you—and the economy

In the heady days after one accepts a new job, a noncompete agreement may seem an innocuous bit of paperwork. These contracts, in which employers bar employees from working in competition after leaving the company, are routinely demanded of nearly one in five jobs in the US, according to a report published by the US Treasury in 2016. Less than 10% of new hires try to negotiate their terms, according to the report.

In the heady days after one accepts a new job, a noncompete agreement may seem an innocuous bit of paperwork. These contracts, in which employers bar employees from working in competition after leaving the company, are routinely demanded of nearly one in five jobs in the US, according to a report published by the US Treasury in 2016. Less than 10% of new hires try to negotiate their terms, according to the report.

But workers who sign enforceable noncompetes pay dearly for their deference, according to preliminary results from new research. Employees bound by strong agreements get lower starting pay than their less restrained peers, and their earnings remain lower throughout their careers, according to a working paper by a team of academic researchers.

The study looks at career trajectories of workers in technology, an industry where most professionals sign noncompetes. Using quarterly Census Bureau data from 30 states, the researchers compare tech worker wages in states with strong noncompete enforcement to those in states that heavily restrict enforcement. The data allowed researchers to follow individual careers, and to compare only workers in the same industries, gender, age, and earnings, at firms of similar size.

Simply starting a tech career in a state that strongly enforces noncompetes reduces earnings up to eight years later, whether or not a person is changing jobs, the study found. Workers constrained by strong noncompetes are less likely to change jobs—a traditional route to higher pay—but more likely to take their skills to other states when they do, according to the results.

The findings are outlined in “Locked in? The enforceability of covenants not to compete and the careers of high-tech workers,” by Natarajan Balasubramanian of Syracuse University, Jin Woo Chang of University of Michigan, Mariko Sakakibara of UCLA Anderson, Jagadeesh Sivadasan of University of Michigan, and Evan Starr of University of Maryland. Balasubramanian, Sakakibara, and Starr each have previously published research on the effects of noncompetes on workers and economies, and their research is heavily cited by the Treasury study.

Their research adds much-needed quantitative analysis to the debate over noncompetes, a source of growing concern for state and federal authorities. The number of noncompetes has risen dramatically in the last decade, and their terms now cover low income earners as well as engineers. Reports by the White House and Treasury in 2016 cited ways the agreements can damage careers and the economy at large.

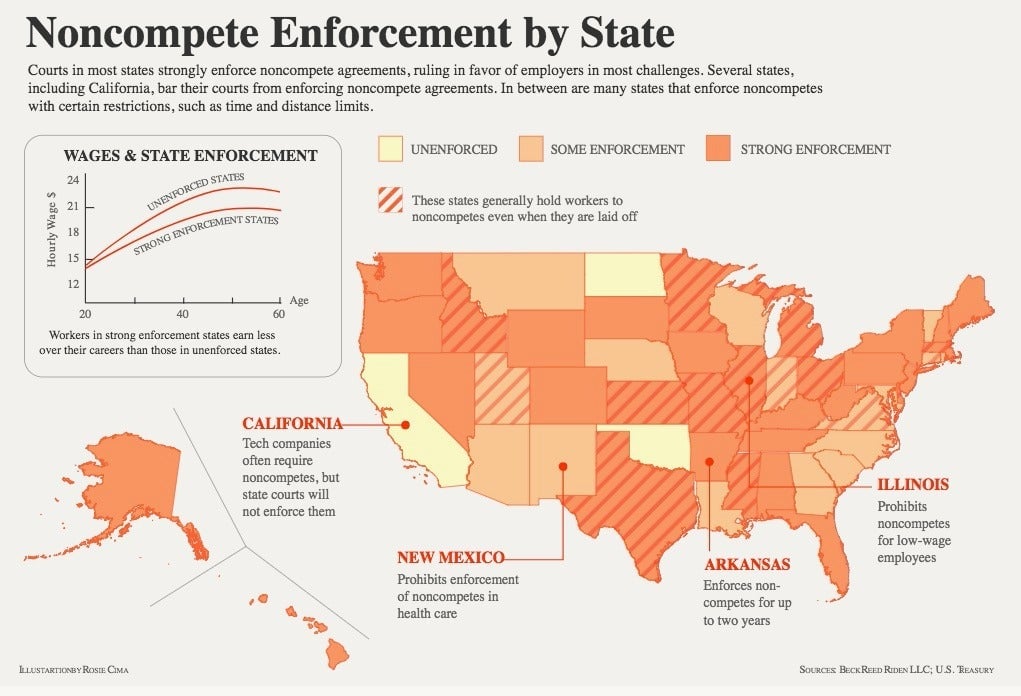

Laws governing enforcement of noncompete agreements are in flux in Oregon, New Mexico, Alabama, Florida, Illinois, and numerous other states, as legislators and courts grapple with how much control companies deserve over careers of former employees. Traditionally, lawmakers supported noncompetes for their presumed ability to draw high paying jobs and top talent to their states. Treasury’s report notes insufficient research in the field to conclude how noncompetes affect economies, and particularly few studies with quantifiable results.

The preliminary findings in “Locked in?” along with related research by its authors, offer surprising details about the kinds of workers covered under noncompetes and the career paths those workers take. Their results so far suggest that noncompetes depress wage growth, entrepreneurship, and the movement of workers. Each is a factor economists consider crucial to a healthy economy.

Career control for the greater good

A typical noncompete agreement prevents an employee, for a certain amount of time, from doing similar work outside the company within a defined geographic area. A sales rep for an insurance company might, for example, be barred from taking an insurance job, or starting an insurance company, within the same state or territory for a year after quitting.

Rationale for such unusual power over individual livelihoods stems from decades-old assumptions about innovation and the things that promote it. Ostensibly, employers invent more readily if they know workers can’t show rivals their trade secrets, including technologies, price lists, sales trends, and customer data. Innovative companies will lay stakes in states that protect their secrets, proponents argue, and their success will bring those states more high-paying jobs. Workers, proponents say, get career boosting training in projects that employers would not pursue without legal protection.

But nearly 30 million US workers are covered by noncompete agreements now, and it’s unlikely that all of them have access to trade secrets, according to research by Starr and University of Michigan’s Norman Bishara and J.J. Prescott. Once reserved for engineers working with top secret technology, recent agreements also restrict career moves for workers making club sandwiches from corporate recipes and $10-an-hour laborers on construction sites. Some 15% of workers without four-year degrees are under noncompetes, and 14% of those earn less than $40,000 annually, according to the study.

The power that states give corporations to pursue noncompetes varies dramatically. California, North Dakota, and Oklahoma all but bar enforcement. On the other extreme, several states bind workers to noncompete agreements even if they lose their jobs in layoffs. Many states legislate some restrictions, such as limits on the distance and time they can cover, or adjudicate enforcement for fairness on case-by-case bases.

Some employers appear to be taking advantage of employees’ ignorance of these agreements, or even bullying them into complying with unenforceable demands with legal threats, according to the White House report. In California, for example, the rate of workers’ signing noncompetes is slightly higher than the national average, even though the agreements are legally powerless there.

One-third of noncompetes are signed after workers accept jobs, and likely after they have given notice to current employers and turned down other offers, according to the Starr, Bishara, and Prescott study.

More skills, less pay

Recent research, including the “Locked in” study and other papers by team members, suggests that noncompetes can be counterproductive to the economic goals they were meant to achieve. Instead of encouraging innovation and higher wages within a state, their findings suggest, enforcing noncompetes lowers workers’ earning power and motivates them to take their skills elsewhere.

A recently updated working paper by Starr finds that employers offered significantly more training when noncompetes were enforceable. But those additional skills don’t translate into higher pay for the workers, according to his results. Starr finds that workers under strong noncompetes earned hourly wages about 4% lower than unbound peers.

“Locked in?” finds that significantly lower pay extends for tech workers in high enforcement states throughout their careers. Over the first seven years, their earnings are about 4.4% lower than unbound peers. High wage earners under noncompetes start their jobs more significantly underpaid, and they lose even more ground over time, according to the findings.

The level of noncompete enforcement also affects the number of times tech workers change jobs, according to the study. Technology workers in Florida, a state with strict enforcement of noncompetes, stay on average 7.5% longer in their jobs relative to technology workers of the same characteristics in non-enforcing California, the study finds.

Brain gain or brain drain?

Attempts to use noncompetes as incentive for economic growth appear to be backfiring. Rather than securing a talented worker pool, enforcing noncompetes encourages “brain drain” by incentivizing knowledgeable workers to move to less restrictive states, according to several studies. “Locked in?” finds that when tech workers in high enforcement states do move, they are more likely to change states than non-tech workers from the same states. The tech workers also were more likely to use their industry skills in their new jobs, the study finds.

Similarly, a study recently published in Management Science by Starr, Balasubramanian, and Sakakibara finds lower rates of within-industry entrepreneurship in states with strong noncompete enforcement. Using data on about 5.5 million new firms in 30 states, they found that strongly bound workers were significantly less likely to build new companies within the same industry.

Although strong enforcement limits the number of competitors, that process appears to create stronger startups than seen in states with lax noncompete enforcement, according to the findings. Startups that came out of existing firms in high enforcement states were more likely to survive and thrive than similar startups in low enforcement states, the study finds.

The results about noncompetes and worker movement are consistent with those in a 2015 Research Policy paper by Matt Marx of MIT, Jasjit Singh from INSEAD, and Lee Fleming of University of California, Berkeley. Their work finds that enforcing noncompetes drives talent to places unlikely to restrict career choices.

Where’s the tradeoff?

In recent years, state legislatures have scrambled to implement or adjust enforcement laws. In October 2016, the White House issued a policy maker’s guide that outlines how various states were addressing overly broad noncompete agreements, particularly those involving low income workers.

But legislative attitudes toward noncompetes remain mixed, according to a summary of state actions on noncompetes published in the Federalist Society report. New Mexico banned enforcement of noncompetes in health care, and Hawaii put similar restrictions on noncompetes in technology.

Many states moved to limit the use of noncompetes to professionals, and to limit the time and distance agreements can cover. Arkansas, Alabama, and Georgia bucked the trend by essentially strengthening corporate rights in the agreements. Florida maintains one of the strongest, allowing enforcement even if the agreement restricts competition.

In the past, the level of noncompete enforcement was couched as a balance between the rights of individual workers and the need to support a healthy economy. If these research findings hold, legislators should find it easier to do both at the same time.

This post originally appeared on UCLA Anderson Review.