Centuries before Myers-Briggs, workplace personalities were assessed using skull measurements

Bosses’ fondness for unscientific personality tests is not a purely modern phenomenon. Currently, two million people every year take the Myers-Briggs test, which sorts them into 16 personality types, including ENFJ (extroverted intuitive feeling judging), and INTP (introverted intuitive thinking perceiving)—none of which have any scientific validity. Two hundred years ago, long before Myers-Briggs arrived on the scene, employees had their skulls measured instead.

Bosses’ fondness for unscientific personality tests is not a purely modern phenomenon. Currently, two million people every year take the Myers-Briggs test, which sorts them into 16 personality types, including ENFJ (extroverted intuitive feeling judging), and INTP (introverted intuitive thinking perceiving)—none of which have any scientific validity. Two hundred years ago, long before Myers-Briggs arrived on the scene, employees had their skulls measured instead.

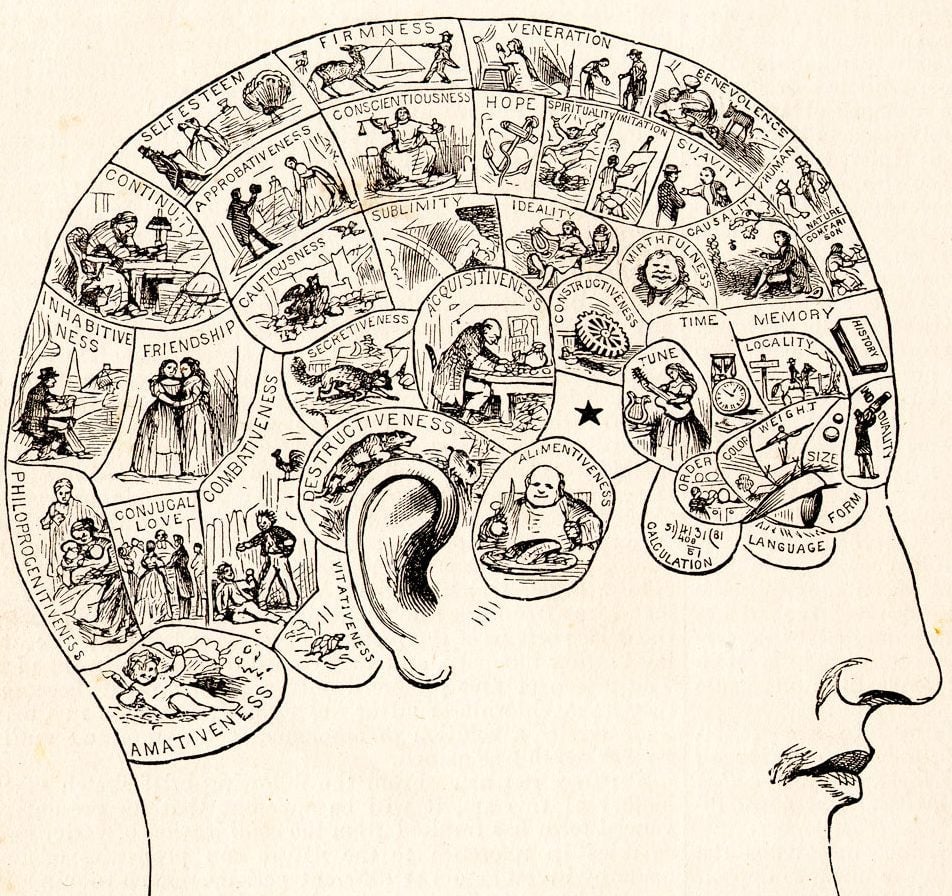

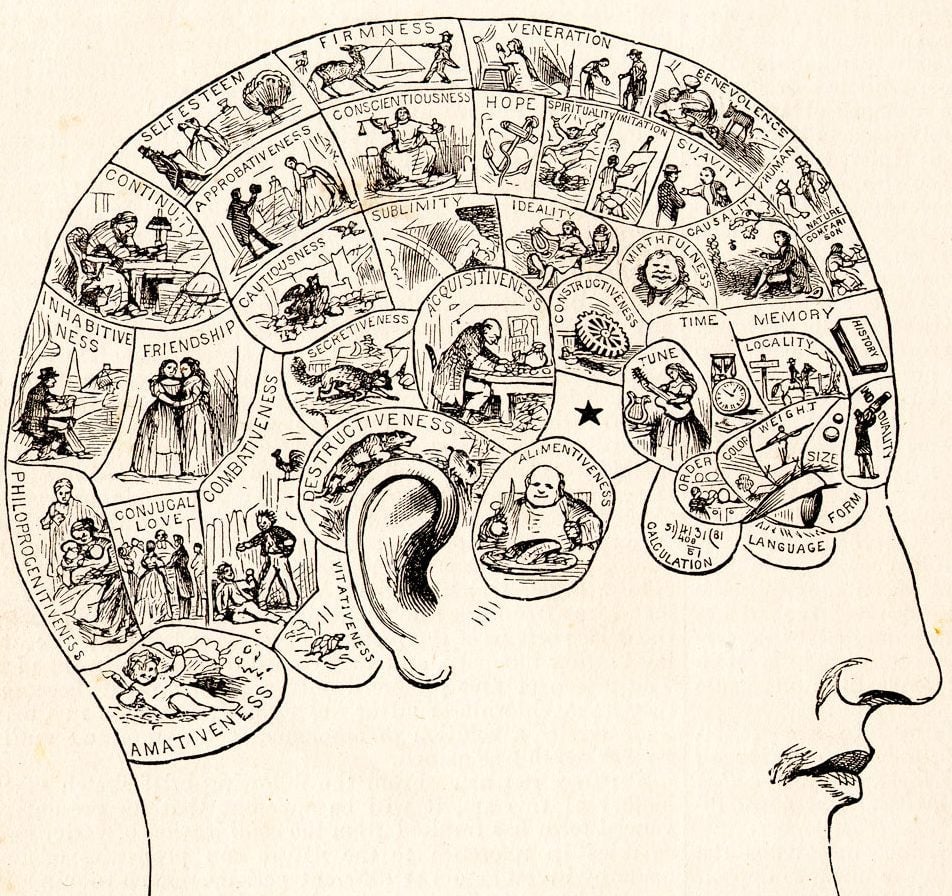

Though it sounds ridiculous now, skull measurements were all the rage at the time, thanks to phrenology. This field is most remembered for using its wildly inaccurate theories in an attempt to justify eugenics, and it was largely abandoned in the 20th century.

But in its heyday, phrenologists’ views were well regarded. The field held that different areas of the brain were responsible for different aspects of personality and that the size of each particular area determined personality type. Phrenologists believed that the shape and features of a skull revealed the size of the underlying brain, and thus someone’s personality.

These theories began in Vienna but spread throughout Europe and the United States. Practical phrenologists, who measured customers’ heads for a fee, could be very precise in their assessments. This pamphlet claims that various skull features could reveal a “total want of sexual feeling,” a “disrelish for food, preferring vegetable to animal diet,” or a “decided aversion to children.”

In Victorian Britain, employers sent job candidates to phrenologists to provide character references. George Combe, a Scottish lawyer and founder of the Phrenological Society of Edinburgh describes this in his Lectures on Phrenology.“I would never employ a clerk who had not a large coronal region,” he writes. “And this has been my practice too with regard to domestics, for the last ten years; I would rather trust to an examination, indeed, than to a certificate of character.”

Combe tells of an applicant for the role of “servant” who “had an excellent coronal region and good intellectual development.” Combe hired her despite a bad character reference from a former employer and “she remained with me three years and behaved excellently.”

The mystery of the former employer’s bad character reference, Combe wrote, was later explained by her own brain: “The lady had a smaller brain, less coronal and intellectual region than the servant, she instinctively felt her inferiority.”

Phrenology tests were also used to judge which career someone should go into. In 1912, one such character analysis of a girl younger than seven claimed, “she will be in her element as a lady doctor or science teacher.”

Clearly, phrenology was not an accurate personality test. But phrenologists did set out key ideas—that the brain is the biological basis for all emotions and thought, and that different areas do have specialized roles—that are widely believed by neuroscientists today. We still have a tendency to colloquially reference these ideas: Calling someone highbrow or lowbrow, for example, is rooted in phrenology.

It’s natural human tendency to wonder about our “true” personality, and seemingly scientific tests respond to this curiosity. Bosses, meanwhile, will always want enthusiastic, diligent employees and inevitably hope they can use tests to reveal the true qualities of their workforce. Even using flawed tests can be worthwhile, as Leah Fessler has reported for Quartz at Work, if used as a jumping off point to discuss personalities. In centuries to come, though, don’t be surprised if the current penchant for Myers-Briggs is seen as ridiculous as skull measuring.