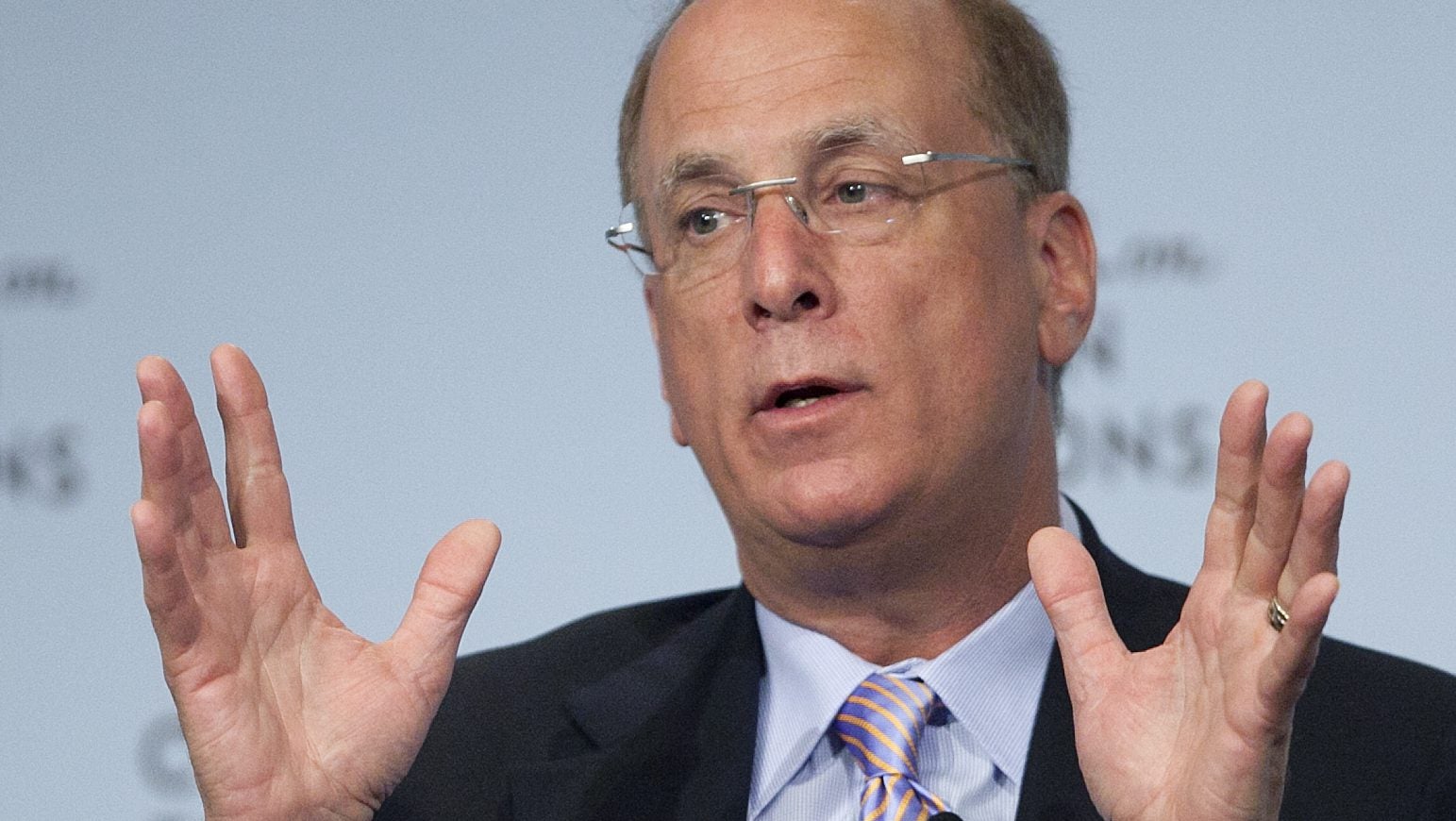

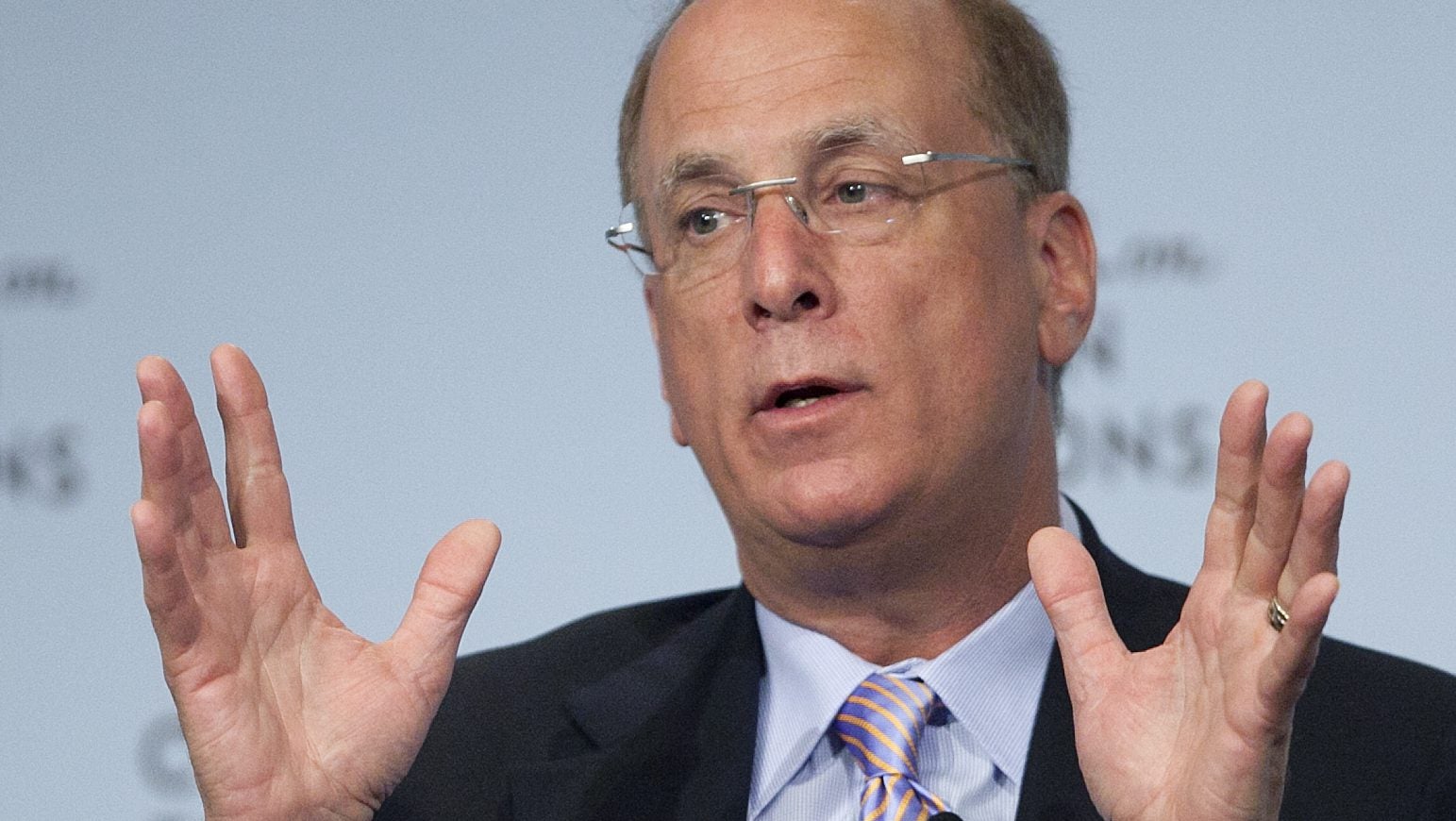

Larry Fink’s letter to CEOs is about more than “social initiatives”

By any measure, Larry Fink’s letter to CEOs this year is a game changer. When the head of BlackRock, the largest investor in the world, says that companies must produce not only profits, but contributions to society, it sends a powerful message. I pray it leads to thoughtful conversation in boardrooms and the c-suite. But that will require a careful reading of the letter itself, not just the early press—which sets up an age-old, worn-out debate about the social responsibility of business.

By any measure, Larry Fink’s letter to CEOs this year is a game changer. When the head of BlackRock, the largest investor in the world, says that companies must produce not only profits, but contributions to society, it sends a powerful message. I pray it leads to thoughtful conversation in boardrooms and the c-suite. But that will require a careful reading of the letter itself, not just the early press—which sets up an age-old, worn-out debate about the social responsibility of business.

Language matters. A lot. Being clear about this moment and what is now required of business is critical. But getting the message right is complicated.

Fink in his letter excels at both clarity and simplicity: “To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society,” he writes in the opening paragraphs. New York Times writer Andrew Ross Sorkin, in turn, while writing about an early release of the letter that reaches CEOs on January 23rd, called BlackRock’s objective “new social initiatives.” Inadvertently, Sorkin translates the clarity and power of Fink’s statement into something that can be delegated to the corporate foundation office down the hall.

More “social initiatives” will not fix our problems.

My advice to CEOs? Read the letter, and then read it again. Fink is not asking companies to engage in more philanthropy. We cannot meet the challenge of today with charity or workplace volunteerism. Instead, we require a solid new foundation for business operations and decision rules, and that requires change in both the C-suite and board rooms. It also means a change in the reward systems and investment decisions of BlackRock and its peers. There is work ahead for all of us.

Boards that are about to parse, and hopefully embrace, Fink’s thoughtful and timely message, should ask themselves three questions:

1. What do we aim to do as a company? What is our Purpose?

Fink makes clear that you should start with your fundamental purpose, and the metrics and message to investors will follow. Get ahead of the activists by clarifying and communicating your long-term plans.

Taking this step of clarifying purpose and metrics seriously can avoid the plight of companies like VW, Wells Fargo, and Uber. But even companies that are borrowing a page from Peter Drucker and sticking with the aim to satisfy customers can no longer do so at the expense of the financial health of workers, families, and the communities that make life supportable. Take Amazon, for example. Consumers love the company because of convenience and cheap goods. But the real cost is revealed in working conditions, which is fast becoming a cause celebre for campaigners, or the waste generated by inexpensive products and free packaging. Real performance is more complicated than what appears in the stock price this month, and smart investors are sensitive to performance in the myriad ways it can be measured.

2. Where are we most vulnerable as a company?

Fink states “companies must benefit all of their stakeholders,” but even that can confuse. A better place for the board to start the conversation is with the business model itself.

What are we taking for granted that is pushing the costs onto others? Economists call these impacts “externalities.” Environmentalists call for “life cycle assessment.” My mother called it cleaning my room and putting my dirty clothes into the wash (and yes, then folding them and putting them away.) The change to be made in companies starts with scrubbing the supply chain of harmful practices related to labor, human rights, and natural resource extraction. But it also requires being astute about the pieces of the puzzle that are most critical in building the long-term health of your business. Where does your footprint matter the most? Where is your opportunity to truly lead?

For Amazon, it will require building a good relationship with the region in which it builds its next headquarters, including a fair tax share for the cost of schools and roads. For Intel and Dow and Boeing, it can mean careful management of the waste that is a by-product of mining and manufacturing up the supply chain. For Apple, it requires knowing the rules and protocols of contractors, who capably deliver a superb product at remarkable speed and efficiency, but also touch hundreds of thousands of workers in remote places. For BlackRock, it means rethinking how it pays portfolio managers to ensure that the reward system is consistent with the values in the Chairman’s office.

3. Are we a good neighbor?

As Rick Wartzman points out in his recent book, End of Loyalty, in the 1950s this meant paying and supporting workers and laborers so they could in turn support their own families and communities—and when times were good, afford the products and services created through their efforts: a vacation, a car, a TV set. Henry Ford’s legacy of paying his workers enough to buy a Model T still serves as an example.

When I first got into the business of connecting business and society in the 1990s, the understanding about what companies owed society was simple: the ‘social responsibility’ of companies was to create jobs and pay their taxes. Today, even this low bar feels strangely complicated. Researchers from University of Texas- Austin and University of Pennsylvania found that a significant contributor to poverty and inequality has been taking the cafeteria workers and the gardeners and the cleaning people off the corporate payroll and benefits. We aren’t going to roll back the clock, and there are good reasons for contracting out services, but it’s become important again to pay attention to the plight of those who are working for you, even if they are on someone else’s payroll. Efficiency and cost reduction cannot come at the expense of financially healthy employees and communities if we are going to rebuild trust in the business system.

Larry Fink, as I read the letter, is asking business to get interested—to pay attention to the unintended costs of doing business and changing social norms, and to be bold in a time of low trust and a glaring disconnect between ‘value’ and values. Henry Ford’s simple act of paying his workers well was self-interested, but it was also bold. It earned him a law suit from a competitor, but they both survived and we benefited from his vision.

Charity and ‘social initiatives’ are unsustainable. What business leaders need now is to re-knit some of the fraying fabric that holds us all together; to conduct their businesses as though they, themselves, are on the other end of the pipe, live on the other side of the wall, are the counter party in the contract. The country, and the world needs our business leaders to get this right.

Judith Samuelson is a vice president at the Aspen Institute.