Dorky motivational posters invented internet memes and changed the way we make fun of work

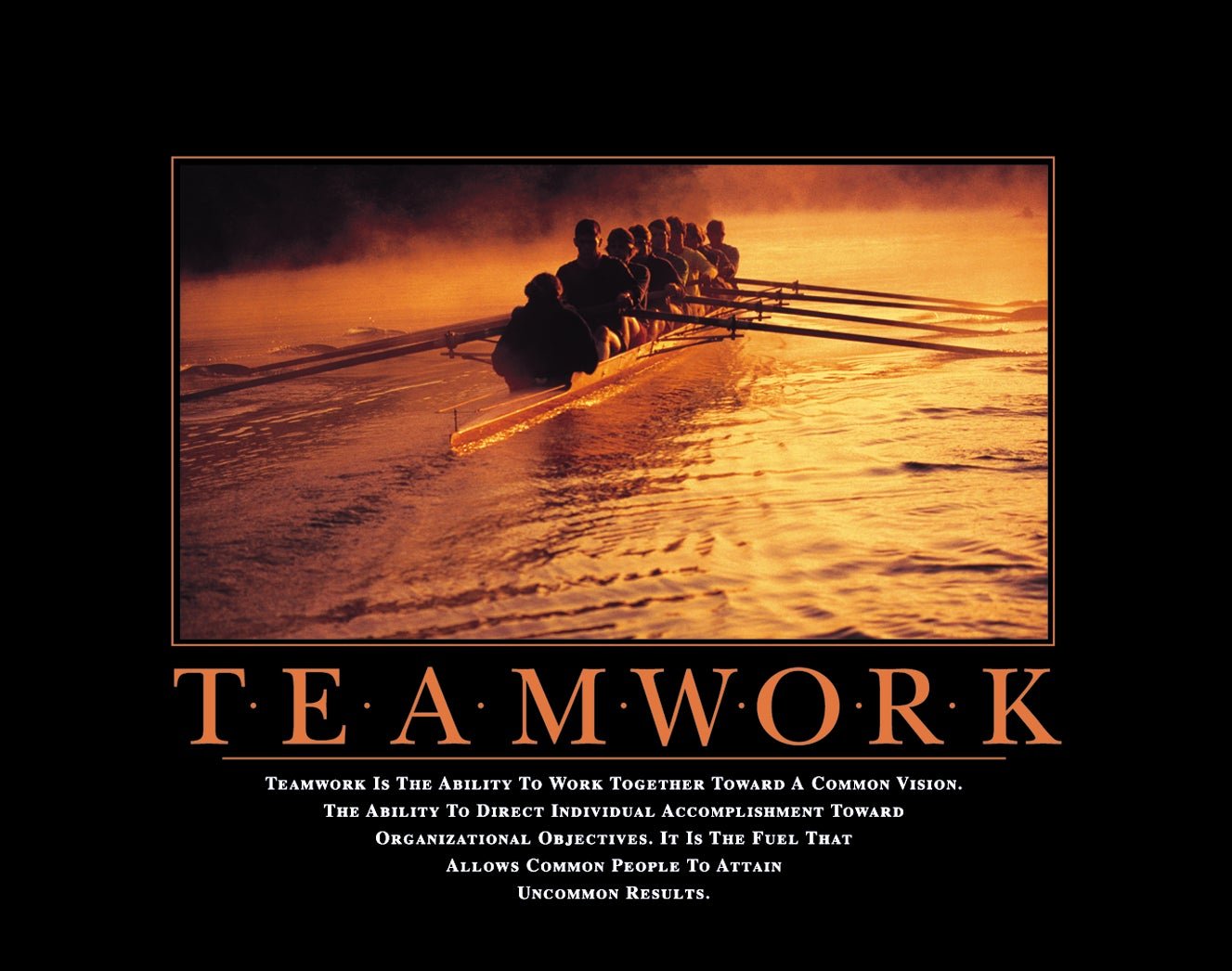

For a time in the late 20th century, a Successories poster was an essential feature of office décor. The format never varied: a black border, a bold-type word, and a forgettable platitude, like “Take the initiative and lead the way” or “The strength of the team is in each individual member.” The posters evoked a particular strain of management culture: earnest, a little out of touch, and resolutely unremarkable.

For a time in the late 20th century, a Successories poster was an essential feature of office décor. The format never varied: a black border, a bold-type word, and a forgettable platitude, like “Take the initiative and lead the way” or “The strength of the team is in each individual member.” The posters evoked a particular strain of management culture: earnest, a little out of touch, and resolutely unremarkable.

They hung in conference rooms and reception areas, as innocuous as the office fern, ideally engineered (as organizational psychologists later would find) to be almost instantly forgotten by the conscious mind. But the story behind the posters is far more dramatic than the placid scenes on their fronts. It’s a tale that includes a splashy public offering, rapid global expansion, and a precipitous fall. Successories played an unlikely, accidental role in the birth of meme culture, and in a specific brand of office humor that targets both workplaces and the hope of success within their confines.

The boom, bust, and rebirth of Successories mirrors the tumultuous changes in the offices it decorated, and in the stories workers tell themselves to get through the day.

The quotation quotient

Successories started in 1985 with a man named Mac Anderson, a serial entrepreneur with a solid portfolio of wholesome American enterprises: a travel company focused on the US Midwest, and a food distributor that Anderson’s website describes as “the country’s largest manufacturer of prepared salads.”

Anderson’s true passion, though, was quotations. Usually people like a quotation because of its content or lyricism, or because they admire its author. Anderson loved quotations for themselves: short, beautiful aphorisms that plucked just the right internal chord.

“All my life I’ve loved quotations. I’ve probably heard every quotation out there,” Anderson told Entrepreneur in 2013. “It’s like looking through the lens of a camera. Sometimes things are blurry, but then you tweak the lens and it becomes crystal clear. You see the quote and say, ‘That’s how I feel!’” (Anderson did not respond to requests for comment.)

For his next venture, Anderson envisioned a product that could fill blank offices walls and empower all those the walls might hold. Working with a small in-house team of designers, he launched in 1985 a mail order catalogue selling posters, T-shirts, mugs, and desk accessories with the company’s proprietary designs. Successories bought the rights to freelance or stock images, chose a phrase, then tied the two together with a quote, often one pulled from Anderson’s vast personal library of inspirational texts.

The connection between the word and the image wasn’t always clear. “SERVICE,” one read, under a photograph of a waterfall. “VISION,” said another, with a photograph of an Outer Banks-type beach scene because . . . well, maybe because without vision, you can’t see a beach?

One of the few early posters that broke the non-sequitur rule featured an image of an eight-person shell rowing across a placid river at sunrise above the word “TEAMWORK.” The shadows and the mist on the water obscure the rowers’ faces; they could be any gender, or any race, or any group of people in the world (at least, any group with access to a boat).

Teamwork, the copy read, “is the fuel that allows common people to attain uncommon results.” The empty text, the faceless figures, the utter forgettability of the photograph itself—together, it added up to bland magic, a poster that could hang on virtually any wall in the world without offense, controversy, or distraction. It was the company’s bestseller, and remains so to this day.

Poster power

Anderson did not invent the motivational poster. Collections of quotable quotes date back as far as ancient Egypt. Victorians embroidered inspiring aphorisms onto samplers. Governments for generations have used motivational posters to nudge ordinary people toward hard things, like stoicism during the Blitz (Britain’s “Keep Calm and Carry On”) or factory jobs in wartime (the US “We Can Do It!” poster, often dubbed Rosie the Riveter.)

But the genre’s big breakthrough—its Gutenberg Bible, if you will—arrived in 1971, when Los Angeles-based photographer Victor Baldwin published a photograph of his Siamese cat Sammy clinging by its paws to a bamboo pole, above the caption “Hang In There, Baby.” The poster sold 350,000 copies in two years.

Baldwin was flooded with letters from people claiming that the sight of the plucky kitten (who in Baldwin’s original photograph looks utterly terrified) gave them the courage they needed recover from illness, accidents, and other setbacks. The poster inspired countless knockoffs, and identified a vast and previously untapped market of people who liked their pep talks in poster form.

The precise mechanism by which a motivational poster motivates is not well understood. Being exposed to a stimulus, even one as seemingly benign as an image on a wall, can have a powerful unconscious effect on later behavior, a concept known as priming. Researchers have found that an “honesty box” for coffee and tea in an office break room gets three times more contributions when a picture of eyes is posted next to the box instead of a picture of flowers. In another experiment, people picked up twice as much litter in a cafeteria when a picture of human eyes was on the wall.

Gary P. Latham, an organizational psychologist at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, has conducted several experiments on the power of motivational posters. In one, 54 call center employees were randomly assigned to work in either a bare room, a room decorated with a photo of a victorious runner crossing a finish line, or one featuring a poster of smiling call-center employees. The workers who saw the runner raised more money than those in the empty room, and those who saw the work-related poster raised the most of all.

Posters “absolutely” have an effect on behavior, Latham told Quartz At Work—just not at the conscious level. Most people in Latham’s experiments don’t actually realize that they’ve seen a poster in the room, he said. Motivational posters are practically made to be discarded by the conscious mind.

Latham said he was once asked during a phone interview if he had any such images in his office. As he looked around the room, he was surprised to realize that it was in fact full of decades-old motivational posters that he, a scholar of motivational posters, no longer consciously registered.

“They’ve been on my wall for 30 some odd years,” Latham said with a laugh. “I’d stopped seeing them.”

Dare to soar

In the 1990s, Successories achieved the kind of heights suggested in its DARE TO SOAR poster (a bald eagle gliding over treetops; “Your attitude almost always determines your altitude in life.”).

The company listed on Nasdaq in 1990, the same year as Cisco Systems. The first brick-and-mortar store opened in a Naperville, Illinois, mall in 1991. According to a company legend repeated in the Chicago Tribune, a businessman en route to New Zealand read about Successories in an in-flight magazine on the first leg of his trip, rented a car during a layover in Chicago, and drove the 60 miles roundtrip to buy some posters to take abroad.

By 1995, according to one company profile, the company had 51 stores and 41 franchise locations in 17 states, plus retail outlets in Australia, Bermuda, Canada, the Netherlands, Ireland, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, South Africa, and the UK.

The stores stocked lapel pins, paperweights, and motivational tapes, but posters were its lifeblood. At its peak in 1996 Successories sold some 3,000 framed images a day, enough for 60 miles of black framing each month—and $56 million in annual sales.

Anderson’s brand of motivation had met the perfect moment. The company debuted the year after Ronald Reagan’s wildly successful “Morning in America” campaign ad proved that unabashed earnestness could be an effective marketing tool. The bestselling nonfiction book of 1984 and 1985 was businessman Lee Iacocca’s Iacocca: An Autobiography, a tome filled with pat motivational phrases—”all business operations can be reduced to three words: people, product, and profits”—that wouldn’t seem out of place on a Successories poster.

As the hard-charging ’80s gave way to the prosperous ’90s, Successories’ inspirational pablum spoke to a public seeking an easily digestible spiritual supplement to its material success. The company’s heyday coincided with the debut of Deepak Chopra’s first books, and a phase on the Oprah Winfrey Show where the talk show host started lighting a lot of candles and schooling viewers in her bespoke brand of spirituality. Profiles of Anderson during this era note that he sometimes played a soothing tape of nature sounds in the background during interviews, like a living, non-ironic embodiment of Al Franken’s Stuart Smalley character on Saturday Night Live.

Successories echoed a message pinging around the culture: You could indeed be good enough, and smart enough, if you just tried hard enough.

“We’re really selling motivation. This is critical to business success in the 1990s,” Anderson told the Chicago Tribune in 1992.

Successories was booming, and so were many of the businesses on whose walls its products hung. The company’s rise coincided with the longest period of economic growth in US history.

And then we came to the end

Then the Internet ruined everything. That, plus some bad business decisions.

In the late 1990s, the nascent dot-com boom kicked an already-productive economy into a frenzy. The posters’ gentle platitudes came as small comfort to overworked offices.

“I finally hung them, but not until our hours went down from 14 to 10 a day,” an office manager for a San Francisco-based logistics company told the Chicago Tribune in 1997, after her employer bought $20,000 worth of Successories posters. “These posters came as a shock to us. When you’re already working 12-hour, 14-hour days, and then you get posters telling you that attitude is everything and to do it right the first time, it doesn’t go over real well.”

There was chaos inside Successories, too. Anderson brought in James Beltrame as COO to restructure after a string of unsuccessful internal promotions and management snafus that Anderson described in his folksy way as “trying to change the oil while driving the car down the road.”

What Beltrame discovered was a business in shambles. The company believed it had turned a profit for the previous year; a closer look at the books revealed that it had in fact lost $7 million. A new automated ordering system collapsed at the start of the holiday rush, leading to millions in lost sales.

“There really wasn’t much that wasn’t broken,” Beltrame told the Chicago Tribune in 1996. “One of the things I said was, ‘Well, you people preach this [motivational] stuff, but it doesn’t look like you’re using it very well in your own business because you’re going down the tubes.’”

The company downsized, restructured, and got back on its feet. But it was too late to capture the innocence of the earlier days, both for Successories and its customers.

The tech bubble burst. And then 9/11 happened. And then the Enron scandal came to light. And by that time, the cheery simplicity of a Successories poster just seemed like a cruel joke, or at the very least an easy one.

As the dot-com bubble was nearing its peak, three overworked tech industry friends spent an evening rewriting a Successories catalogue with captions of their own. Within a few years they launched Despair Inc., a direct parody of Successories. Despair Inc. also sold a TEAMWORK poster, but theirs had a photo of a snowball and the words “A few harmless flakes working together can unleash an avalanche of destruction.”

The parodies’ grim resolve resonated with post-recession workers. Successories posters by that point were so ubiquitous that Despair Inc.’s “demotivational” posters were easy to pass off on people who had long ago stopped paying attention to the frames on the office wall.

In the early 2000s, a colleague at the suburban newspaper where I worked snuck into the office one night and quietly swapped the Successories poster in the conference room for a Despair Inc. one that read “Motivation: If a pretty poster and a cute saying are all it takes to motivate you, you probably have a very easy job. The kind robots will be doing soon.” If any boss noticed, they never said anything, and the team held meetings under the poster until the office shuttered in 2007.

As if to prove Despair Inc.’s point, the real Successories was collapsing. The company was never swift to adapt to change—that switch to automated ordering nearly kneecapped it in the mid-1990s. Despite the lessons imparted in the company’s CHALLENGE poster (“It is not always the strongest people who win, it is the people who never back down from a challenge”), adapting its analog retail business to a digital age was one obstacle too many.

In August 2002, Nasdaq delisted the stock. Anderson sold the company to a private investor for an undisclosed amount in 2004. It changed hands several times and was sold in 2009 to Teddy and Warren Struhl, a pair of brothers and entrepreneurs who relocated the company from Illinois to Boca Raton, Florida.

Successories’ new owners believed in the motivational mission and wanted to return the company to its original identity as a vendor of motivational office decor, adapted to the digital age. But the Struhl brothers had a bigger problem than a competing parody poster company: an Internet full of free parody posters.

Unbeknownst to them, their most iconic product had become a template for one of the earliest and most popular internet memes. Unlike physical poster sellers, meme makers didn’t have to worry about buying image rights. Photoshopped parodies of Successories posters proliferated much faster than the real thing, glomming up searches for actual motivational posters with pages of goofy, filthy, or otherwise offensive knockoffs.

“Google was not as sophisticated at the time and would pair us next to ‘demotivational’ posters. Our product was nothing when compared to what the whole wide world could create in over a year,” said Vincent Nero, the company’s vice president and general manager. “Unfortunately that’s not very good for one’s brand.”

A new era

Fortunately for Successories, the Internet’s sense of humor changes a lot faster than trends in office décor. Demotivational poster-style memes are an ancient relic of a pre-gif era. The internet moved on, and Successories re-established itself as a purveyor of inspiration for a tech-savvy world.

Successories now employs 26 people and counts 84% of the Fortune 500 among its clients, Nero said. It sells the kind of personalized awards that companies give out in-house for performance and customer service, plus motivational swag: clocks, stress balls, a leather tote bag that says “Thanks for all you do.”

And, of course, it still sells posters. Some have a slightly refreshed design, but the bestsellers are the classic original images, untouched since the glory days of the 1990s: An eagle soaring over the word “EXCELLENCE”; those rowers and their Teamwork; the words “Customer service is not a department . . . it’s an attitude” under, for some reason, a picture of a waterfall.

In the company’s early days, the people placing orders for Successories posters were mostly female, Nero said: secretaries and administrative assistants tasked with decorating the office. Buyers are still mostly women, he said. But now they are managing those offices, and looking for something that will inspire employees to do their best.

“Our typical Successories customer, the buyer is a female in a management position, over the age of 35, with a salary over $75,000, trying to manage an office and motivate people,” Nero said.

The company is smaller than it was in its heyday, but its ethos is everywhere. The same woman who orders a Successories poster for her office is also seeing motivational quotes as she scrolls through Instagram or Facebook, or hearing them read aloud by the teacher in the YouTube yoga class she does after work. Motivation has become just another form of media, one that can be accessed through ways more private and personalized than the shared experience of a poster on a wall.

And yet, this might be an ideal time for a Successories comeback. The posters aren’t interesting, but they are immune to division, offense, or controversy. Like Muzak or pretzels in the breakroom, nobody loves them, but for the most part everybody can live with them. At a time when many people aren’t sure what to say in their workplace, there may be no more unifying choice than something that says, essentially, nothing at all.