How to make better use of everything you read

I once downloaded a speed-reading app that would flash individual words across my phone. I aggressively set the rate to 400 words per minute and braced for the onslaught. I used this system to parse essays, primers, and long-form interviews, all in the name of advancing my career. Yet, all I had to show for it was a massive headache and a zero-percent retention rate.

I once downloaded a speed-reading app that would flash individual words across my phone. I aggressively set the rate to 400 words per minute and braced for the onslaught. I used this system to parse essays, primers, and long-form interviews, all in the name of advancing my career. Yet, all I had to show for it was a massive headache and a zero-percent retention rate.

This failed experiment led me to reexamine my reading habits. Yes, I am a committed to learning and improving myself via reading. Yes, I keep an intimidatingly long Instapaper reading list for all the articles I’ve yet to get to. But what I was really searching for when I started out on my ill-conceived attempt at speed-reading, I later realized, was a way to access everything I had already read.

I read a lot, and I read pretty quickly. It’s retaining all that information that I find challenging. In the digital age, our options for note-taking feel antiquated and haphazard. I’ve tried so many approaches: taking photos of whole pages of notes or books, taking screenshots of text and posting them to Twitter, forcing myself to write book reports in my Evernote. These were all reactive approaches, though, and unsurprisingly, none have stuck.

What I needed was a system built from first principles that would help me access what I’ve read, when I needed it. So that’s what I developed.

Principle 1: Skimming is OK

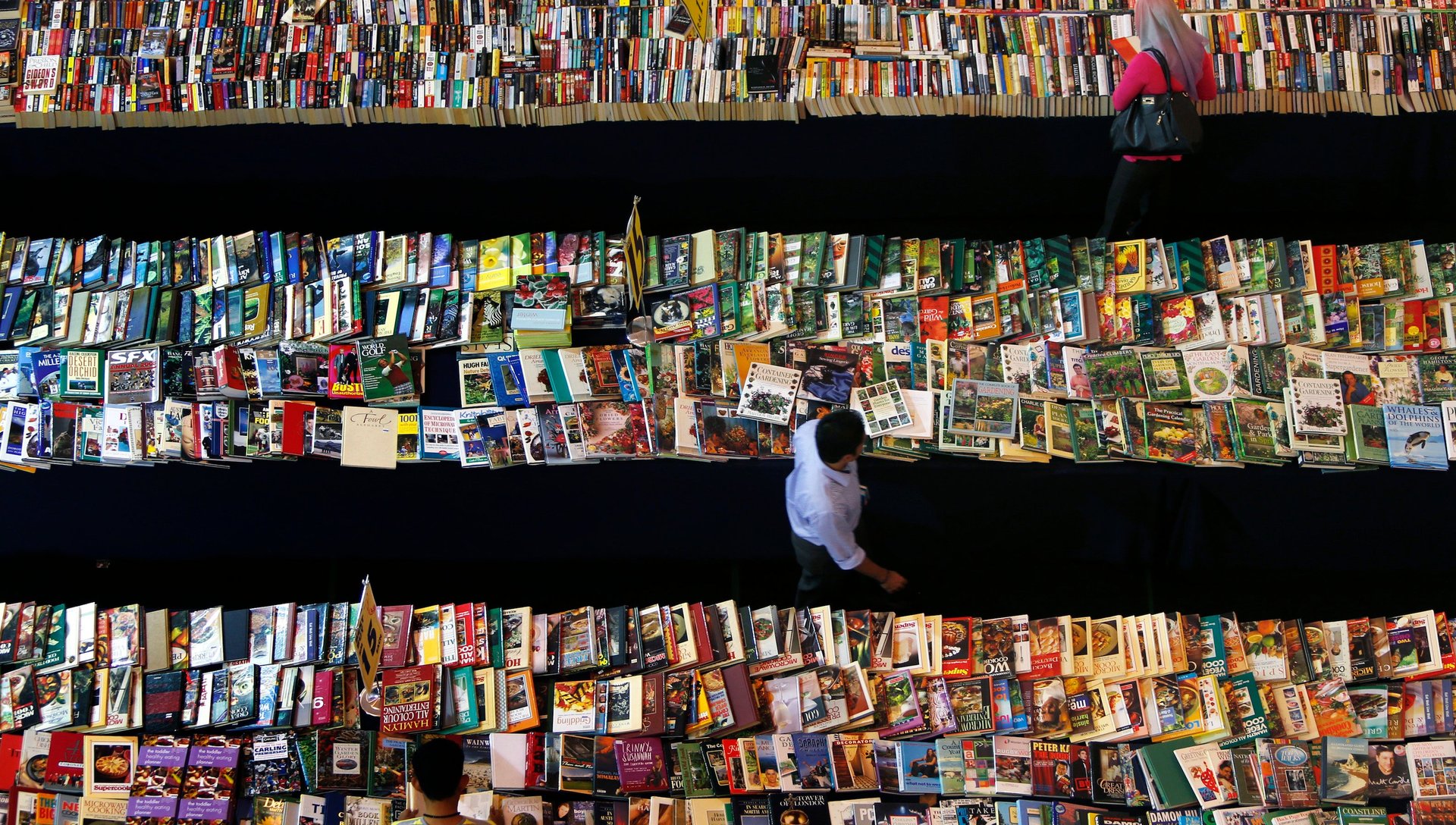

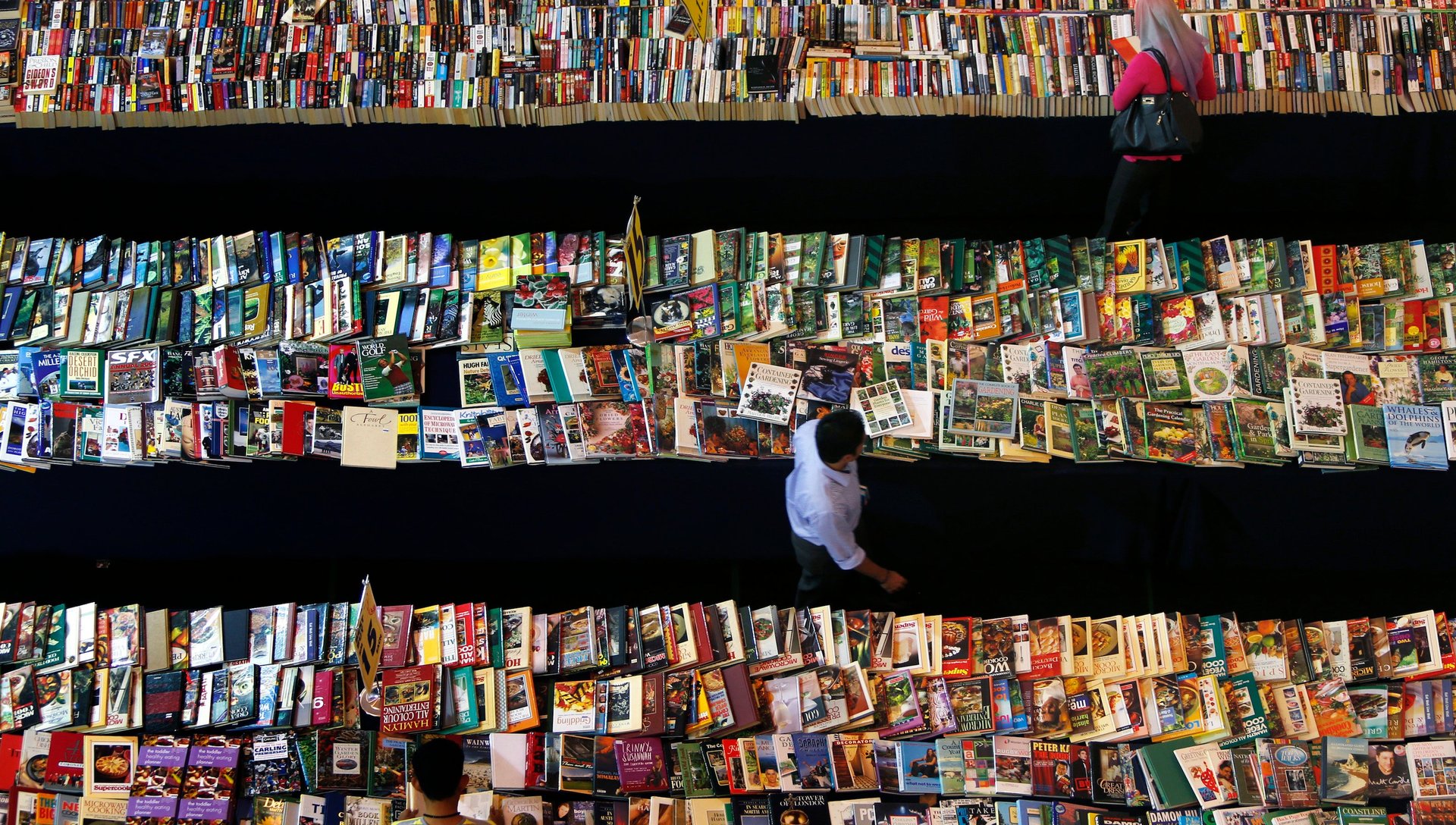

Neuroscientist, author, and avid reader Sam Harris says he has a “woozy” feeling that “most books are too long.” Harris speculates that “publishers can’t charge enough money for 60-page books to survive; thus, writers can’t make a living by writing them.” Robert McCrum, associate editor at the Observer, attributes what he calls “literary elephantiasis” to “the pile ’em high tradition” of US bookshops and their tendency to “display big fat books in the window.”

Personally, I’ve found that nonfiction, particularly business books, are too long. The arguments tend to be relatively straightforward but are frequently done in by too many overlapping examples. Even excellent books, like Yuval Harari’s Sapiens, can start to feel like a slog in their final chapters.

In the 1940s classic How to Read a Book, philosopher Mortimer Alder described a structured way to skim a book. It involves understanding the structure of a book through its table of contents, index, and preface, and then “dipping in here and there, reading a paragraph or two, sometimes several pages in sequence” and “listening for the basic pulsebeat of the matter.” Skimming pairs well with our next two principles.

Principle 2: Don’t over-index to tomorrow

Have you ever spent a huge amount of time taking detailed, formatted notes, only to never look at them again? Herein lies the challenge with digital note taking: you don’t know if, how, or when you’ll need to access the notes in the future—which means that investing a huge amount of time upfront in note-taking can be a colossal waste.

Tiago Forte, the founder of productivity consultancy Forte Labs, describes this conundrum as follows: “How do I make what I’m consuming right now easily discoverable for my future self?” He calls his approach Progressive Summarization, which involves “summarizing and condensing a piece of information in small spurts, spread across time, in the course of other work, and only doing as much or as little as the information deserves.”

Forte’s approach gives me permission to discard the tags, summaries, and heavy formatting of my notes. There’s a good chance I’ll never refer back to them, so I don’t waste the input time. Yet as we’ll see in the third principle, skipping the heavy investment at the start doesn’t mean you can’t access the information at a later date.

Principle 3: Steal from tech

If you’re a Gen-Xer or older, you’ll probably remember a time at school when you were asked to memorize facts. The scientific term is recall memory, but unless you’re trying to win your local watering hole’s trivia night, facts such as state capitals, math equations, or the dates of historical events are a waste of brain resources in the era of Google.

There’s more good news for those who were never great at memorization. Tech has made words, photos, and videos easily searchable, even within the gated gardens of our personal data.

There’s no reason your note-taking can’t reflect the enhanced recall memory that technology now provides us.

Putting it all together

I’ve finally landed on two systems that seem to do the trick, one for online articles and one for eBooks. They operate on the same principles, and allow me to recall what I need when I need it, without requiring too much labor for the necessary inputs.

Reading a web-based article: First, sign up to three free apps/services: Instapaper, Evernote, and IFTTT. Once the first two are downloaded, use IFTTT as a connecting glue between these two apps and activate the following rule: Append Instapaper Highlights to Evernote.

I read all my web articles through the Instapaper app, which allows you to bookmark content and read it later on any device, like a phone, tablet, or laptop. As I encounter interesting passages, I use the app’s highlighter to capture the entire paragraph.

As I’m highlighting, behind the scenes IFTTT is copying and then appending each paragraph into a Evernote dedicated to that specific article. (It’s important to grab the entire paragraph, versus a specific sentence, to help your future self retain the context.) And that’s it. I never even have to touch Evernote and my highlights will live on digitally, forever.

Reading an eBook: The approach here is similar, but it requires a different combo of apps, notably Kindle and the Chrome extension Bookcision. As I’m reading a book on the Kindle app, I’ll highlight the paragraphs I might want to recall later. Once done, Bookcision will grab all of the highlighted sections and export them into a single text file, which can then be dumped into Evernote or any other digital notebook.

Helping out your future self

You can definitely stop here and be confident that your highlights will always be searchable by your future self. But if you want to improve the chances that you someday find the relevant part of your notes, there are three additions that could tilt the odds in your favor.

- Bolding/highlighting: I don’t overthink this step, because it can be time consuming. But for the hard-hitting pieces/books, I’ll go through and mark up key passages once they’ve been saved in my notes. (This is why it’s helpful to have the full context of the paragraph.)

- Dropping in keywords: At the bottom of the note, I do a quick stream-of-consciousness dump of the keywords related to this note. This might include the author’s name, publication name, key ideas, or even the name of the person who sent me the article. I avoid using formal tags, because the purpose here isn’t to catalog the notes. I’m just trying to make the information within them discoverable via search, with as little friction as possible.

- Creating specific notebooks: This will let you tailor your search to only your reading notes, cutting through the noise of everything else you may have saved.

I should clarify that I don’t closely adhere to this approach when reading for pleasure—this is strictly business. When I read for pleasure, I tend to want to drift into a story and often find myself more emotionally invested and unwilling to highlight aggressively. That being said, I still grab resonant passages and export the notes, because, you know—my future self!

Either way, the whole approach is predicated on speed and discoverability, and on the humbling fact that we don’t know what our future selves will care about. Thankfully, tech can be an ally in this quest—though it still won’t help us win trivia night.