The most successful people in the world aren’t masters

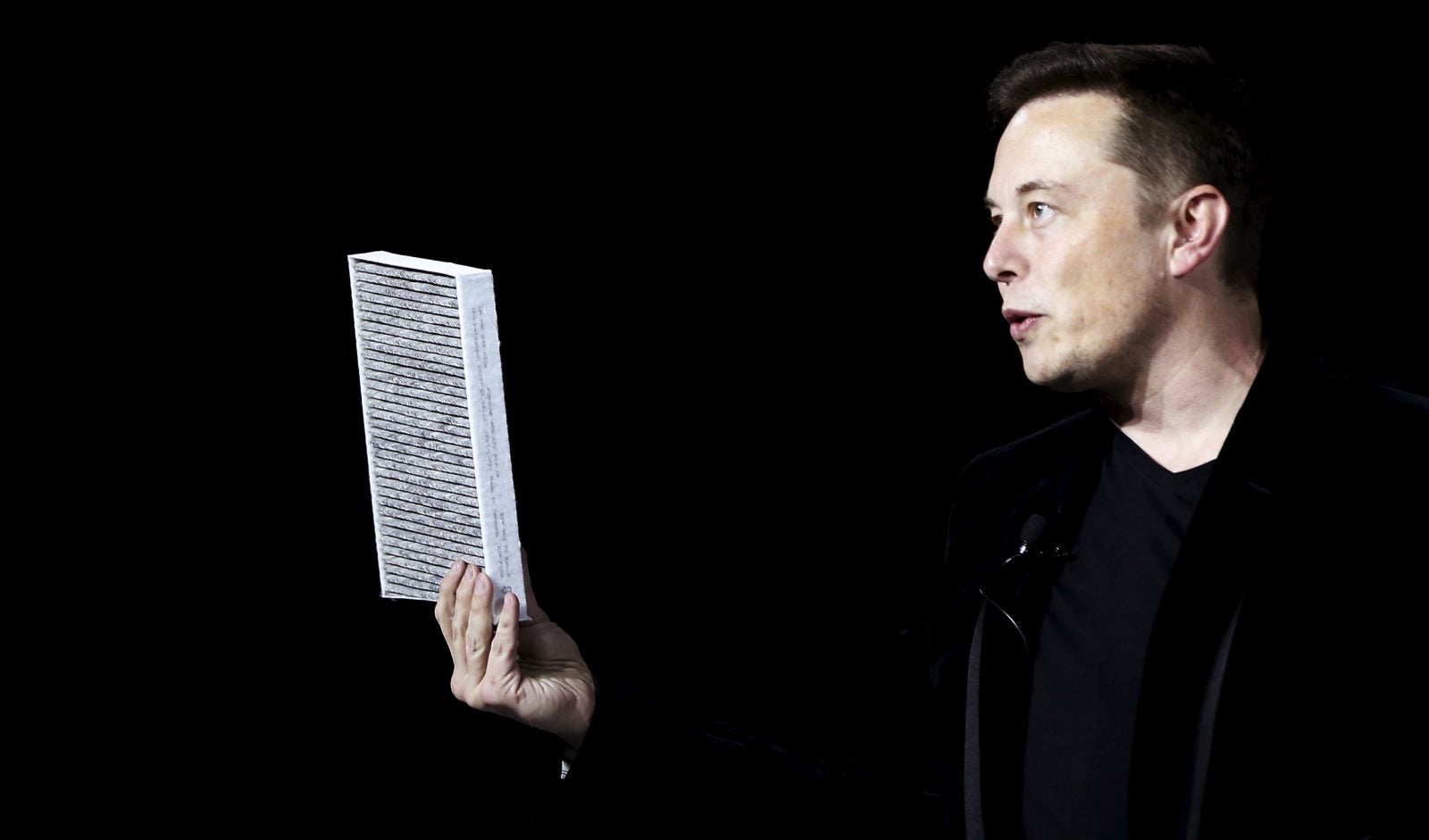

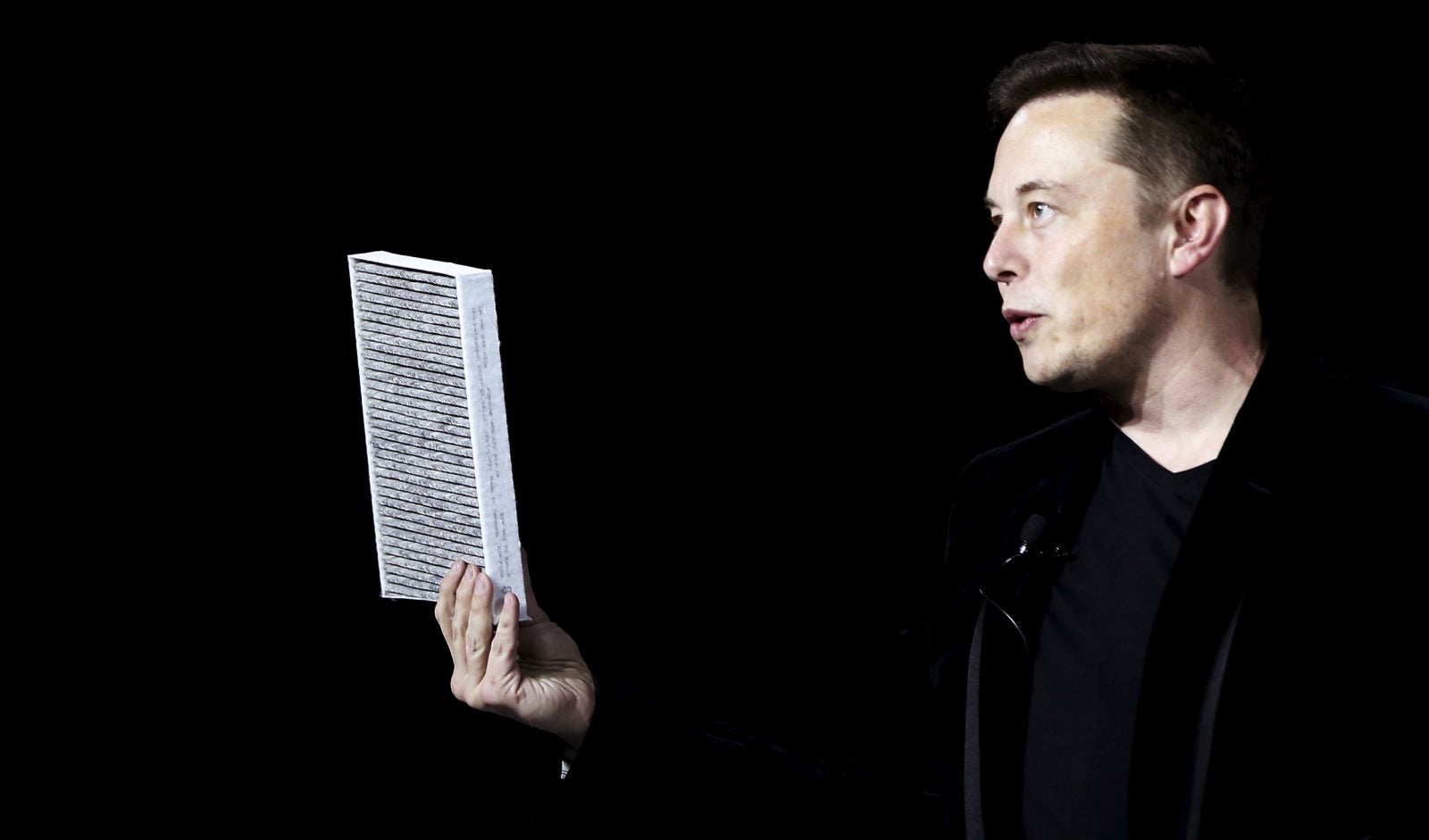

As a teenager, Elon Musk read 14 books per week. At peak Olympic training, Michael Phelps spent six hours in the pool every day. Before they invaded America, The Beatles played eight-hour nonstop gigs in Germany, multiple nights a week.

As a teenager, Elon Musk read 14 books per week. At peak Olympic training, Michael Phelps spent six hours in the pool every day. Before they invaded America, The Beatles played eight-hour nonstop gigs in Germany, multiple nights a week.

Practice, so they say, makes perfect. And according to author Malcom Gladwell, 10,000 hours of practice makes mastery. (As Gladwell explains in his book Outliers, studies in elite performance demonstrate “an extraordinarily consistent answer in an incredible number of fields,” which is that “you need to have practiced, to have apprenticed, for 10,000 hours before you get good.”)

But various psychologists—including the scholar whose research Gladwell’s argument is based on—counter the 10,000-hour rule, arguing it’s over-extrapolated or outright wrong. Gladwell himself acknowledges the theory is often misinterpreted: “Practice isn’t a SUFFICIENT condition for success,” he noted in a Reddit AMA. And yet, conventional wisdom still holds that the most successful people pop out of the womb spewing genius and/or devote more practice to a single trade than the rest of us could ever imagine.

Adam Grant, a renowned organizational psychologist, has a rather different take. The Wharton professor and author of Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World has devoted his career to investigating the traits and practices of innovators like hedge fund founder Ray Dalio, Daily Show host Trevor Noah, and Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg. His mission: to demystify the nuances of their profound success.

And as Grant explains in a recent GQ interview, a trait each of these icons shares is actually the opposite of obsessive practice:

“What separates the good from the great is the willingness to try new things. So often successful people and successful groups get stuck in a rut because they basically follow the same routines that have made them successful. If you’re a sports team, that just makes you more predictable. If you’re a company, it means you choose to stand still and make it easy either to miss major waves of change, or for other companies to disrupt you. And as an individual, it means you don’t grow.

So I would love to see every individual, every group try at least one experiment every week. Whether that’s shifting the structure of your meetings, or rotating around the leader for that decision—you can make a long list of what kind of experiments might be relevant. But to me, that’s kind of the big lesson of organizational psychology: the people who are willing to try new things beat the ones who don’t.”

Or, as Grant tells Quartz At Work, “Practice makes perfect, but it doesn’t make new.”

The importance of trying new things shouldn’t surprise us in a world driven by technologies that didn’t exist a decade ago. (Indeed, no skill is more ancient, or essential, than adaptation.) Ultimately, though, it’s not the experiments themselves, but rather the willingness to experiment beyond one’s expertise—which demonstrates a humble disposition toward admitting and exploring your own ignorance—that separates highly innovative people from those who silo their success.

“Evidence suggests that there’s a curvilinear relationship between expertise and creativity,” Grant says. “For example, expert accountants are worse than novices at adapting to new tax laws, and expert bridge players do worse than novices when you change the rules of the game.”

Deliberate practice does help us master basic routines and skills to the point that they put us on autopilot, freeing us up for more creative thought, says Grant. “But it also risks over-learning, where you take for granted assumptions that you should be questioning.”