The “Arrested Development” interview exposes the myth that male anger is part of the “creative process”

Everyone gets frustrated and angry at work sometimes. But responsible people don’t lash out at their colleagues. They understand their negative emotions are not someone else’s problem.

Everyone gets frustrated and angry at work sometimes. But responsible people don’t lash out at their colleagues. They understand their negative emotions are not someone else’s problem.

Actor Jeffrey Tambor has long failed to meet that basic standard of conduct, according to reports of his on-set behavior that include temper tantrums on the sets of both Transparent and Arrested Development (which he admits), as well as sexual misconduct against two of his Transparent colleagues (which he denies). Now a New York Times interview with Tambor and his fellow Arrested Development castmates sheds light on how Tambor has been able to get away with his self-admittedly “volatile and ill-tempered” behavior for so long: He’s surrounded by male colleagues who make excuses for him, and who uphold the harmful myth that ignoring other people’s humanity is simply a part of the creative process.

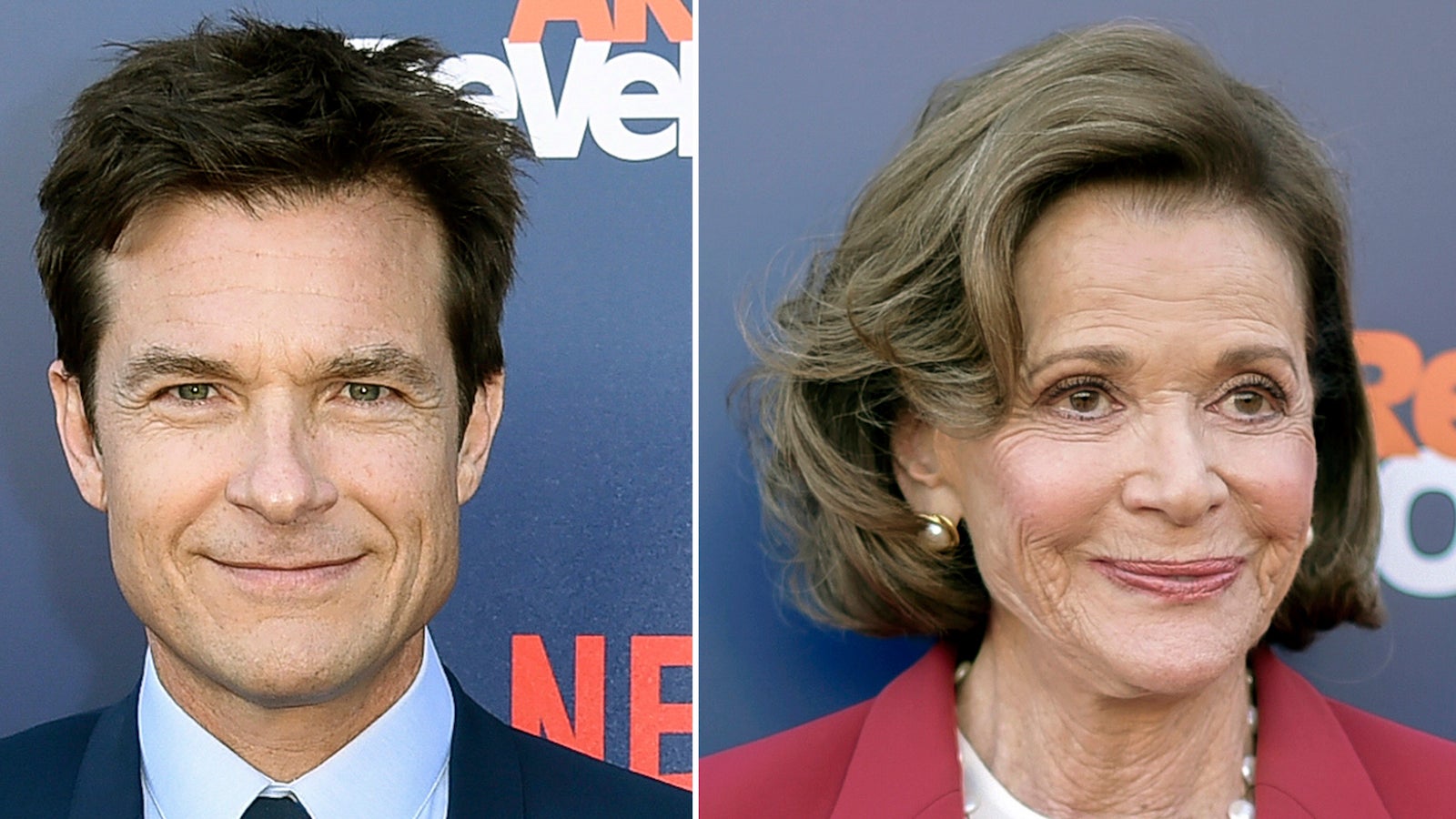

The crucial component of the Times interview turns on an incident which Tambor characterizes as a “blowup” between himself and actress Jessica Walter, who plays his wife on Arrested Development. Exactly what happened isn’t explained, but Tambor apparently unleashed a torrent of verbal abuse on Walter, who is still affected by it today. “In like almost 60 years of working, I’ve never had anybody yell at me like that on a set,” she says, tearing up as she discusses the memory with Tambor and her fellow castmates sitting beside her.

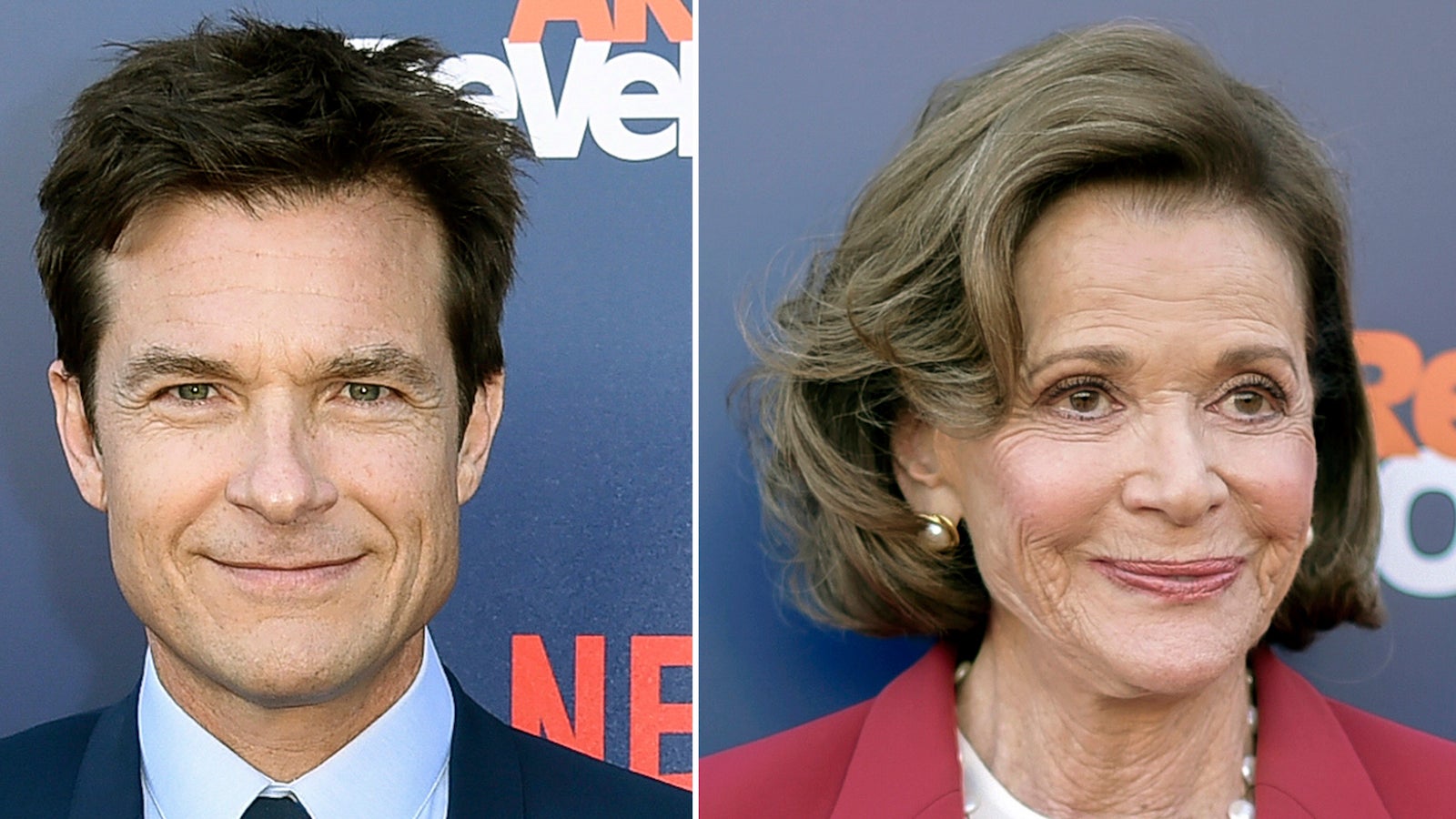

And yet Jason Bateman and other Arrested Development actors immediately tried to minimize Tambor’s actions, implying that screaming at your female coworker is all part of an average day’s work in the Hollywood business. After the New York Times reporter mentions that Tambor yelled at Walter, Bateman cuts in:

BATEMAN: Which we’ve all done, by the way.

WALTER: Oh! You’ve never yelled at me.

BATEMAN: Not to belittle what happened.

WALTER: You’ve never yelled at me like that.

BATEMAN: But this is a family and families, you know, have love, laughter, arguments—again, not to belittle it, but a lot of stuff happens in 15 years.

Of course, family members shouldn’t scream at each other for no reason, either. Later, Bateman switches tactics, suggesting Tambor is just one of those difficult, temperamental creative types that you have to accept in order to make great art.

BATEMAN: Again, not to belittle it or excuse it or anything, but in the entertainment industry it is incredibly common to have people who are, in quotes, “difficult” … Because it’s a very amorphous process, this sort of [expletive] that we do, you know, making up fake life. It’s a weird thing, and it is a breeding ground for atypical behavior and certain people have certain processes.

There’s no doubt Hollywood is weird, and sometimes stressful. All jobs are. But Tambor himself has admitted that on the set of Transparent, “I had a temper and I yelled at people and I hurt people’s feelings. And that’s unconscionable.” It really is—and there’s no part of the creative process that makes it necessary to act as if other people’s feelings matter less than your own. As Jen Statsky, a writer for The Good Place, noted on Twitter, “these jobs are silly and you’re insanely lucky if you get to do it so to be abusive to anyone as part of your ‘process’ is fucking bullshit.” (Note that Tambor isn’t on the show—she’s making a broader point about working in television.)

And yet, as Adam Epstein writes for Quartzy, “All kinds of sketchy behavior by men towards women in Hollywood has long been rationalized as simply part of the process…. It’s an oft-quoted chestnut in the industry that director Alfred Hitchcock had real birds attack actress Tippi Hedren during the filming of The Birds to film her authentic fear and horror. (Decades later she revealed the sexual abuse he also subjected her to.)”

Indeed, it’s worth remembering that the kind of bullying Tambor subjected Walter to is part and parcel of a broader culture of sexism at work. You have to have a certain degree of entitlement and ego to even consider behaving the way that Tambor did. You have to believe you can get away with clearly unprofessional behavior, and be accustomed to considering yourself the most important and talented person in the room. Most women and minorities don’t have that kind of privilege. A lot of white men do.

Bateman has since apologized for his comments during the interview. “I was so eager to let Jeffrey know that he was supported in his attempt to learn, grow and apologize that I completely underestimated the feelings of the victim, another person I deeply love—and she was sitting right there!” he wrote on Twitter. “I’m incredibly embarrassed and deeply sorry to have done that to Jessica. This is a big learning moment for me. I shouldn’t have tried so hard to mansplain, or fix a fight, or make everything okay. I should’ve focused more on what the most important part of it all is—there’s never any excuse for abuse, in any form, from any gender. And the victim’s voice needs to be heard and respected. Period.”

It seems fair to take Bateman’s apology in good faith. But his initial response is worth remembering because it so accurately captures our cultural impulse to shrug off unacceptable behavior from people in power—particularly in the creative realm. When we normalize bullying or aggressive behavior, we clear the way for racist, sexist, and flat-out cruel institutions to remain in place. The dehumanizing of others is never an acceptable price to pay for good work.