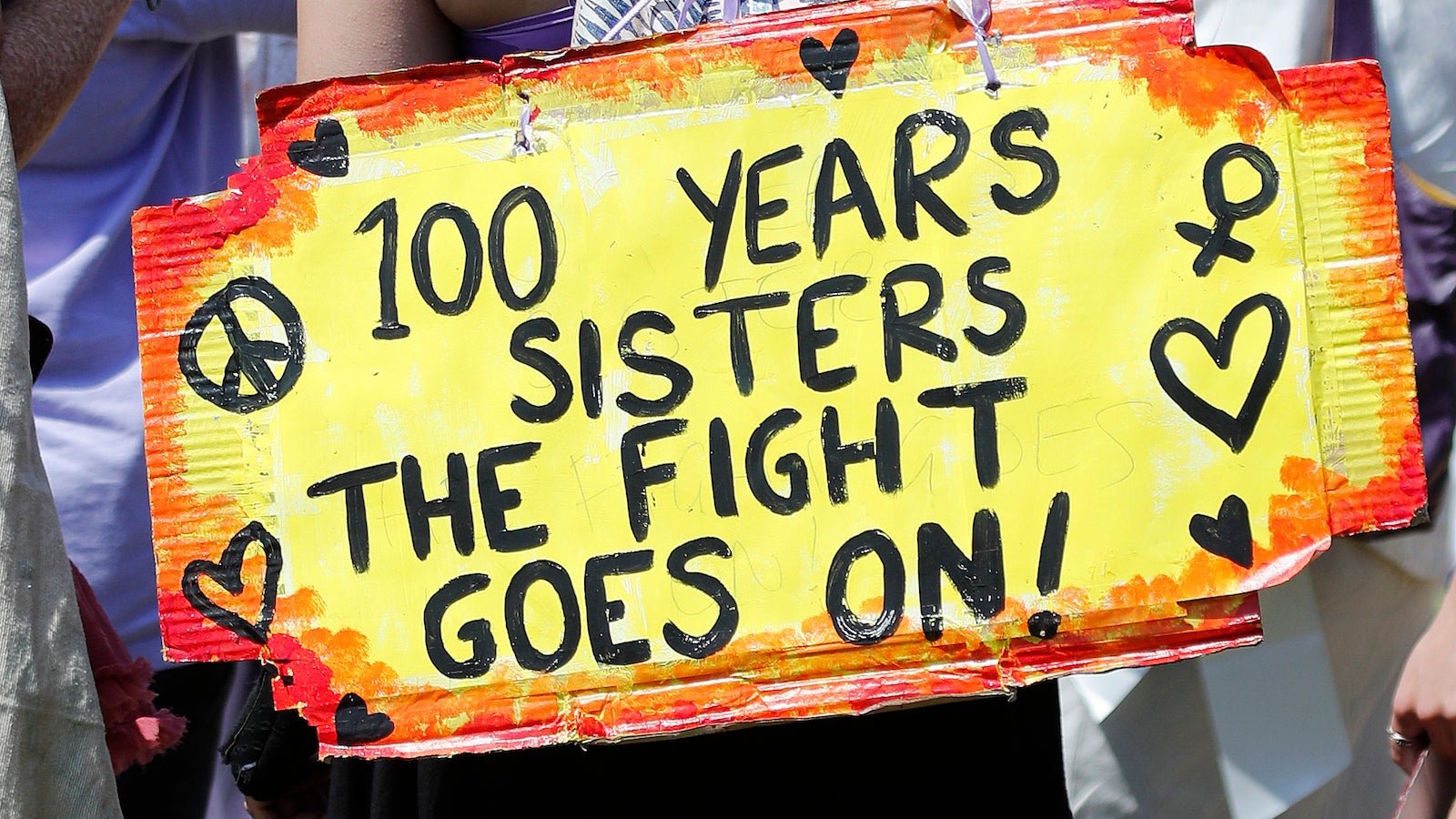

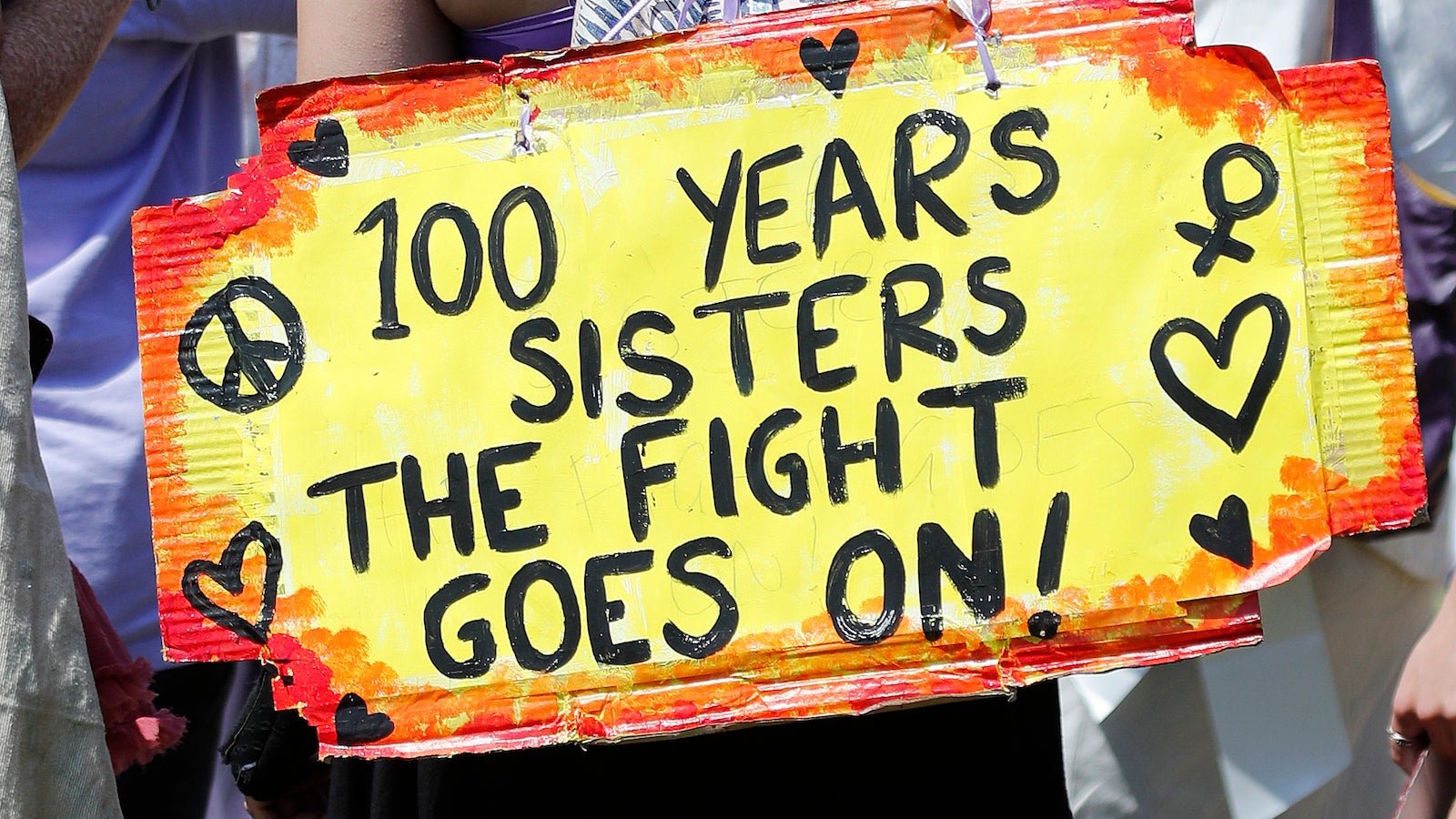

An anti-suffrage poster from 1920 epitomizes today’s fears about women’s progress

To understand today’s anxieties about women’s progress in the workplace and the dismantling of traditional gender roles, we’d be smart to rewind the clocks to August 1920, the climax of American women’s century-long fight for suffrage. The epicenter of this tension: Nashville, Tennessee.

To understand today’s anxieties about women’s progress in the workplace and the dismantling of traditional gender roles, we’d be smart to rewind the clocks to August 1920, the climax of American women’s century-long fight for suffrage. The epicenter of this tension: Nashville, Tennessee.

Summer 1920: The context

Throughout the sweltering summer of 1920, the battle between suffragists and anti-suffragists mounted, as both sides lobbied furiously to secure votes among Tennessee legislators either for or against the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution, which would grant women the right to vote.

By August of that year, 35 of the 36 necessary states had ratified the Susan B. Anthony Amendment (which would become the 19th Amendment), leaving Tennessee as a crucial vote. While nearly every other southern state had rejected ratification, the resolution passed swiftly in the Tennessee state senate on August 13. The state’s house of representatives, however, was deadlocked.

The Tennessee Assembly would cast its final vote on August 18—the suffrage movement’s Alamo moment, as Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win The Vote, calls it. Nashville was flooded with the nation’s leading pro- and anti-suffragists, corporate lobbyists, religious and political leaders, and huge quantities of Jack Daniels whiskey, which anti-suffragists pushed upon legislators so they’d be too intoxicated to congregate.

Under these influences, legislators who’d pledged to ratify began flipping, and the mood among feminists grew tense. “Tennessee rests as a heavy load on our minds,” Alice Paul’s secretary, Emma Wold, wrote to a Women’s Party staff member, as documented in The Women’s Hour. “Anita Pollitzer [another leading suffragist] telegraphs that the vote will be taken tomorrow.. and she has very little hope of a favorable result.”

With the 1920 presidential election just months away, and 27 million women’s votes on the line, the Tennessee ratification battle would quite literally determine the nation’s future.

Among the more influential activist groups present was the Southern Women’s League for the Rejection of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, a union of women from every southern state led by Josephine Pearson, who also served as president of the Tennessee State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Pearson and her colleagues worked tirelessly to ensure they wouldn’t receive their own right to vote. They relied heavily on propaganda preaching that women’s suffrage would destroy southern womanhood and chivalry.

Anti-suffragists, illustrated

Emblematic of the anti-suffragists’ message is “America When Feminized.” The political cartoon poster, created by Pearson’s Southern Women’s League, makes claims such as “a vote for federal suffrage is a vote for female nagging forever;” “women’s suffrage would masculinize women and feminize men;” and “the history of ancient civilization has proven that a weakening of the man power of nations has been but a pre-runner of decadence in civilization.”

It shows a hen in a “Votes for Women” sash leaving her nest behind, as her “husband” rooster calls to her, “Why ma, these eggs will get cold.” She calls back: “Set on them yourself, old man, my country calls me!”

When women imprison themselves

What’s most interesting about this broadside, Weiss says, is that it was created by women, to disenfranchise women. But it also speaks to men. Perhaps most telling is the caption under the illustration of the hen flying the coop, so to speak, which reads: “Suffragist-Feminist Ideal Family Life.”

“Clearly, it reaches into the deepest insecurities of American men, as it’s threatening machismo,” she explains, noting that female anti-suffragists also created cartoons asking who will wear the pants in your family if women get the vote, and showing women in suffrage outfits holding whips as their husbands cower under the bed.

“But it also goes deeper than that, because these anti-suffrage women are saying the vote is going to disturb the American home. It’s going to alter gender roles in a way that is disruptive and unhealthy,” Weiss explains. “It’s going to make women compete with men—the anti-suffragists argue there will be more divorces because husbands and wives will argue about which candidates to vote for—but even deeper, it unsettles the idea of what the family is.”

What this cartoon is really pointing to, says Weiss, is that the idea of women’s suffrage, and the constitutional amendment, is not just a political fight:

“It’s not just about whether women should be able to vote. It’s far more steeped and emotional and complex; it’s a cultural decision and a societal decision, and for some people, truly a moral decision. It’s much more than just a simple political act, or a simple bill or amendment to allow women to become full citizens. These women say very matter of factly that women’s suffrage will bring about the moral collapse of the nation.”

Even more coded within the hen-pecking broadside is that it’s not just motivated by southern women’s internalized sexism. “This cartoon is truly just complete racism,” says Weiss.

Beyond implying that suffrage will degrade women by putting them in the dirty world of politics, female anti-suffragists also assert that the 19th Amendment, if ratified, will permanently threaten white supremacy. ”It will give the vote to all women, and that includes black women,” says Weiss. “That means black women are equal to white women. And that’s going to lead to social equality, they threaten, which will bring down the entire structure of white supremacy, and in turn America.”

From hen-pecking to pussy-grabbing

When I asked Weiss what remains relevant about the “America When Feminized” poster, she laughed. Then replied: “Everything.”

Read out of context, this poster could easily have been designed by any of the misogynists influencing America’s sociopolitical conscious today.

As Weiss explains:

“It really could be now. You know, today we’re told a woman can’t make decisions about her body. There are some movements—I don’t take them seriously—but there are some movements to repeal the 19th Amendment. We’re told that half of our nation, women and immigrants, does not really count. You saw a lot of this same fear of gender role inversion with marriage equality. And of course, every working mom has faced this idea that you’re leaving the nest, you go outside the home, your children are going to suffer for it.

And there are a record number of women running for office this year, which is tremendous, but there’s something kind of unusual and strange and maybe unnatural about that, the idea that women could enter the public sphere in the same way as men. I hope we’ve gone beyond this poster’s misogyny and white supremacy a bit, but when you see news photographs of all white male panels and committees in Washington making decisions about women’s health, you question how far we have come.”

She’s right. To think of feminist progress as one-way trajectory toward parity is to ignore the ever-present reality that in America, there is no politics or progress untainted by misogyny or racism.

While we may be more coded in our anxieties about women’s progress today, America’s most powerful institutions—and the men who run them—still stake their control on the assumption that women do not deserve the right to self-determination. For proof, consider the #MeToo movement, the gender pay gap, or the sheer reality that Donald Trump, who bragged about grabbing women “by the pussy,” was elected president. For women of color, the attempts at degradation are only amplified, as suppression of racial equality—when not presenting itself outright—pulses beneath our politics, culture, and economics as powerfully, and surreptitiously, as it did in that 1920s poster.

A surprising ending

Ultimately, the Tennessee General Assembly did ratify the 19th Amendment, much to the suffragists’ surprise. For this, we can thank Harry Burn, a 24-year-old representative who changed his vote to support ratification last-minute, due to his elderly mother’s pressure.

Opponents then worked feverishly to rescind the ratification vote on constitutional technicalities. Some anti-suffrage legislators even fled Tennessee to Alabama, so to prevent a quorum in the General Assembly. But on August 26, 1920, US secretary of state Bainbridge Colby issued a proclamation of ratification for the 19th Amendment, making it part of the US Constitution.

Delicious as that ending seems, it wasn’t without its consequences. Anti-suffragists in Tennessee went after Burn’s mother, and symbolically rescinded the resolution’s ratification. “We tend to think, oh, by 1920 women have been at this for almost a century, the time had come, and men saw the light,” says Weiss. “But no, it wasn’t like that at all. And it still isn’t like that today.”