How to lead like Abraham Lincoln, according to a Harvard historian

Record numbers of first-time candidates are staking their claim in midterm contests all over the country. These people include Native Americans, combat veterans, members of the LGBTQ community, and women from both parties. As various pundits and entrenched politicians deride these newcomers, we must remember that many of our greatest leaders were once unknown and largely untested.

Record numbers of first-time candidates are staking their claim in midterm contests all over the country. These people include Native Americans, combat veterans, members of the LGBTQ community, and women from both parties. As various pundits and entrenched politicians deride these newcomers, we must remember that many of our greatest leaders were once unknown and largely untested.

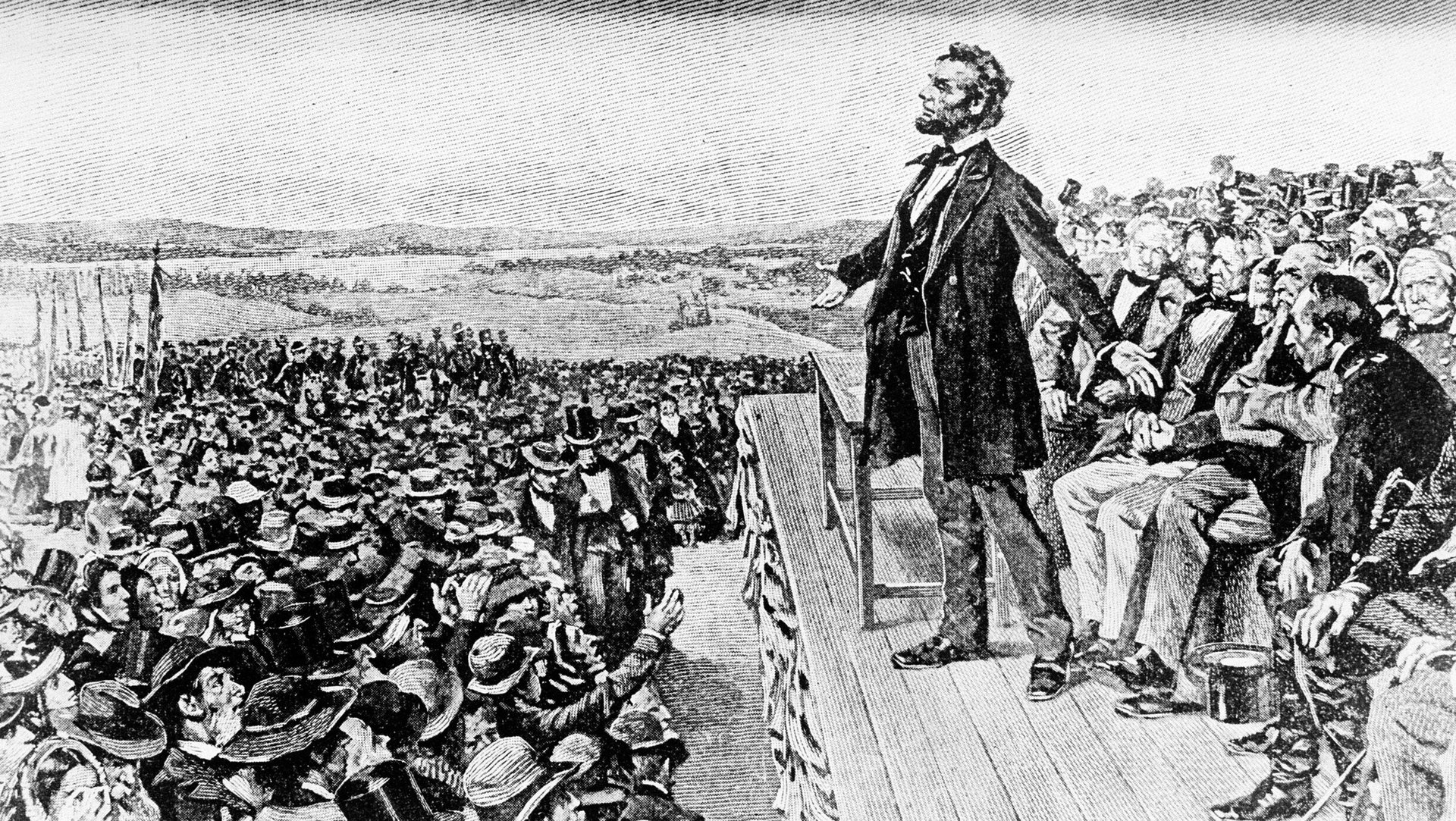

Few people better personified this transformation than Abraham Lincoln, who had less than a year of formal schooling. As I explain in my latest book, through ongoing self-education, he made himself into a skilled attorney, one of the best writers and orators in American history, and our most revered president. His life’s journey was not smooth or easy; indeed, Lincoln failed much more frequently than he succeeded. However, what he learned during his tragedies and triumphs, including the importance of making tough choices when the stakes are high, can help rising leaders today. Here are some of the most important lessons we can glean from Lincoln’s example:

- Know your mission: Make sure you know why you’ve chosen to step into a leadership role, whom you are leading, and the stage upon which you will affect change. This knowledge was critical to both Lincoln’s initial mission when becoming president, which was to save the Union, and equally important to his larger mission, which took shape with the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862: saving the country and transforming it by abolishing slavery.

- Look widely at the big picture: Slow down and take a macro view before you begin. Make sure you understand what is at stake—not only now, but also going forward. Be certain as well that you recognize the interests of the different players and where they stand in relation to your mission. Lincoln made himself into a master of surveying the big picture before he made a major decision. Whether he was deciding how aggressively to prosecute the Civil War, how to think about bringing the country back to together as the conflict wound down, or how to ensure greater equality for Black Americans, he took careful stock of the larger situation, including his potential allies and opponents.

- Focus on no more than three things: Ask yourself what must be done and what can only you, as the leader, do to achieve this. By focusing on the one, two, or three critical aspects of your mission—but no more—you give yourself a much better chance to succeed than if you are constantly dividing your energy among 10 or more tasks. Once these key responsibilities have been identified, let remaining concerns go by either giving yourself permission to turn your attention away from anything not central to your purpose or by handing peripheral issues to others—even adversaries. Recognize that you cannot do it all and that by saying “no” to the nonessential you are, in fact, saying “yes” to what is most important. Lincoln learned this vital lesson as a lawyer arguing cases before hundreds of juries. He came to realize that virtually every case came down to one, two, or three essential issues, and if he could win those points with the jury, he would win the trial. He also came to understand that by focusing only on the fundamental issues he could give the rest away, thus disarming his opponent.

- Solicit advice widely, but take ultimate responsibility: It’s important to listen to many different opinions, but in the end, you are accountable for your decisions. You will wind up saying “yes” to some advisors and “no” to others—there’s no way around the fact that you cannot please everyone—but the ultimate responsibility is yours, even if it makes leadership lonely at times.

- Be Aware of the trade–offs: Something will be gained and something will be lost from every hard decision. It’s essential you understand what these are—as well as who will be affected by such tradeoffs—so you can articulate them to your followers and other stakeholders. Lincoln taught himself to articulate the pros and cons of an important problem or situation to other people so they understood the stakes involved, what a given course of action meant for them, and where the country was headed. His ability to lay out these tradeoffs was rooted in his ability to slow down and then harness deep intellectual and emotional analysis in order to frame the issues properly for himself and for those who looked to him to lead.

- Understand the power of doing nothing: It is natural to want to take a swing when tempers are running hot, but this reaction usually makes things worse and is a big part of why our public life today has become so dysfunctional. One of Lincoln’s greatest strengths was understanding the power of doing nothing in the heat of the moment. He understood that we rarely make good decisions when emotional temperatures are high and, as a result, he cultivated the self-discipline to take no action in such circumstances. Consider, for example, the immediate aftermath of the battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 (the 155th anniversary of which we marked earlier this month). Lincoln was furious that Union General George Meade decided not to pursue the demoralized Confederate troops as they headed south—with an eye toward decisively crushing the enemy once and for all. The president poured his fury into a scathing letter to Meade, writing, “I cannot adequately express my disappointment in this situation.” He signed it and put it in an envelope—but he never sent it (The letter was discovered in Lincoln’s desk after his death.) By doing nothing, Lincoln made a conscious decision to not risk alienating the Northern general and thus potentially sabotaging his mission to save the Union. Expressing white-hot emotions in the moment, as Lincoln realized, often wreaks damage to the world, your followers, and a noble cause. By contrast, sitting with your emotions and resisting the temptation to act on them does no harm (and, in some cases, may even give the issue at hand the time and space to sort itself out). The power of doing nothing is especially important in our age of instant (and often incendiary) communication on social media.

- When critics attack, you must hold the line: This can’t be stressed too strongly. You must keep bolstering your muscles of moral courage in the face of critics—and make no mistake, they always come. For example, as the Civil War grew more and more brutal in the summer of 1864, Lincoln faced censure on all sides. In the North, many Americans demanded an end to the carnage—even if such a peace meant Southerners would keep their slaves. To make matters worse, it was a presidential election year, and as the cries for peace grew ever louder, Lincoln realized he would probably be defeated in November. For almost two years, he had insisted that the permanent end of slavery MUST be part of a Union victory. Now, this position threatened to cost him the election. By August, he was racked with worry. He knew he could not turn his back on the promise of the Emancipation Proclamation; he could not send black soldiers, who had fought so bravely for the Union and black freedom, back to Southern slaveholders. “I should be damned in time & in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends & enemies,” he explained. Still, as the hot summer days stretched on, with no end to the war in sight, the pressure on Lincoln to end the war on any terms had become so great that he drafted a letter intimating he would entertain peace negotiations with the Confederacy. But, once again, he did not send the letter right away. Instead, he asked the abolitionist Frederick Douglass (who had come to see Lincoln on another issue) for his advice about the letter. The African-American leader counseled against sending it, and Lincoln took this recommendation, putting the letter aside and rededicating himself to achieving an end to the war that abolished slavery forever. A few weeks later, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman captured Atlanta and turned the tide of war decisively in the North’s favor.

Nancy F. Koehn is a historian at the Harvard Business School and the author of Forged in Crisis.