Don’t ignore the dread you feel about going back to work

Last week, I didn’t open my laptop once. I had an idyllic vacation where the only words I read were in novels, rather than Twitter or emails, and where my body and mind sunk into a state of deep relaxation, free from the inundating stresses of everyday life.

Last week, I didn’t open my laptop once. I had an idyllic vacation where the only words I read were in novels, rather than Twitter or emails, and where my body and mind sunk into a state of deep relaxation, free from the inundating stresses of everyday life.

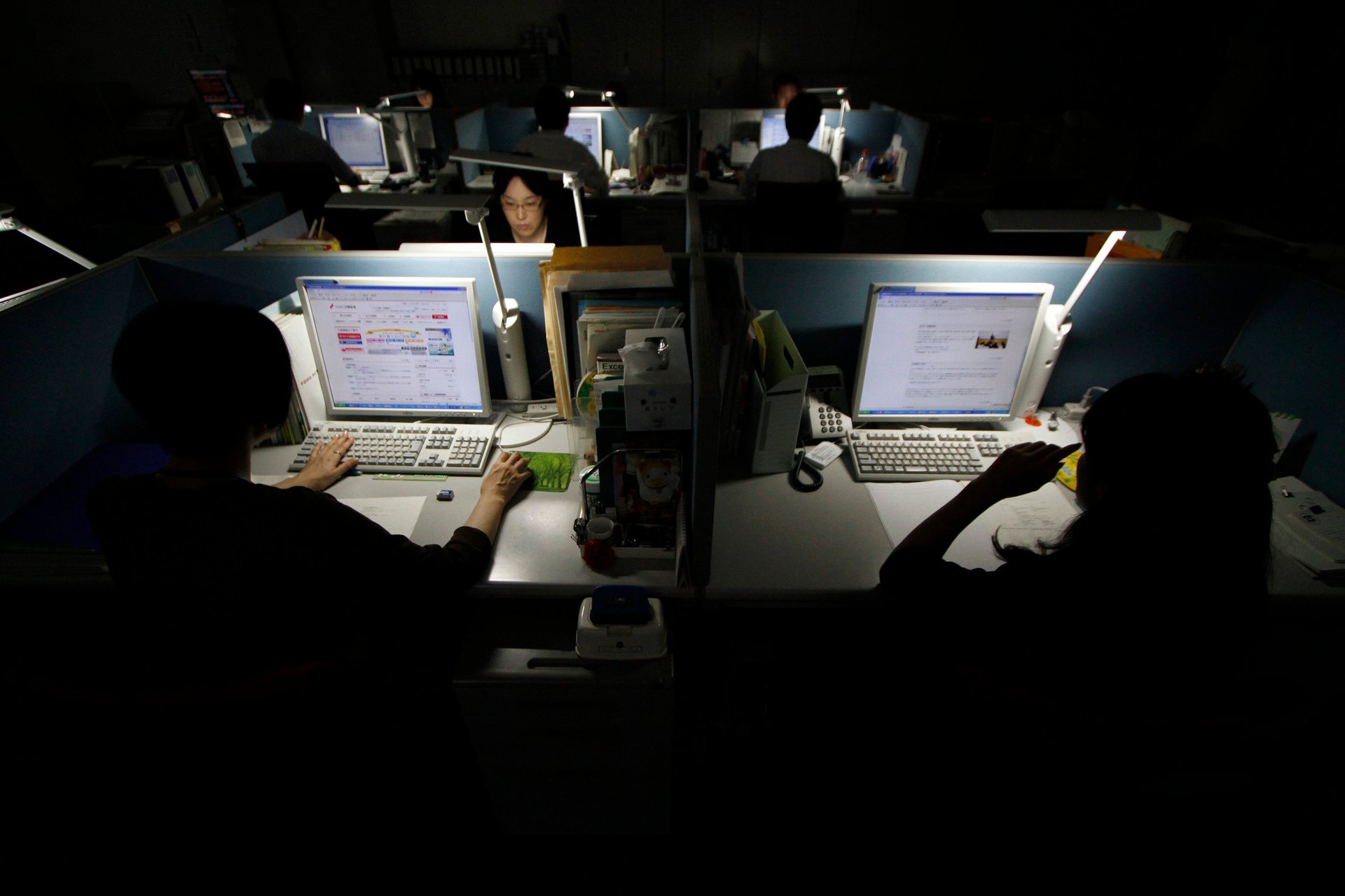

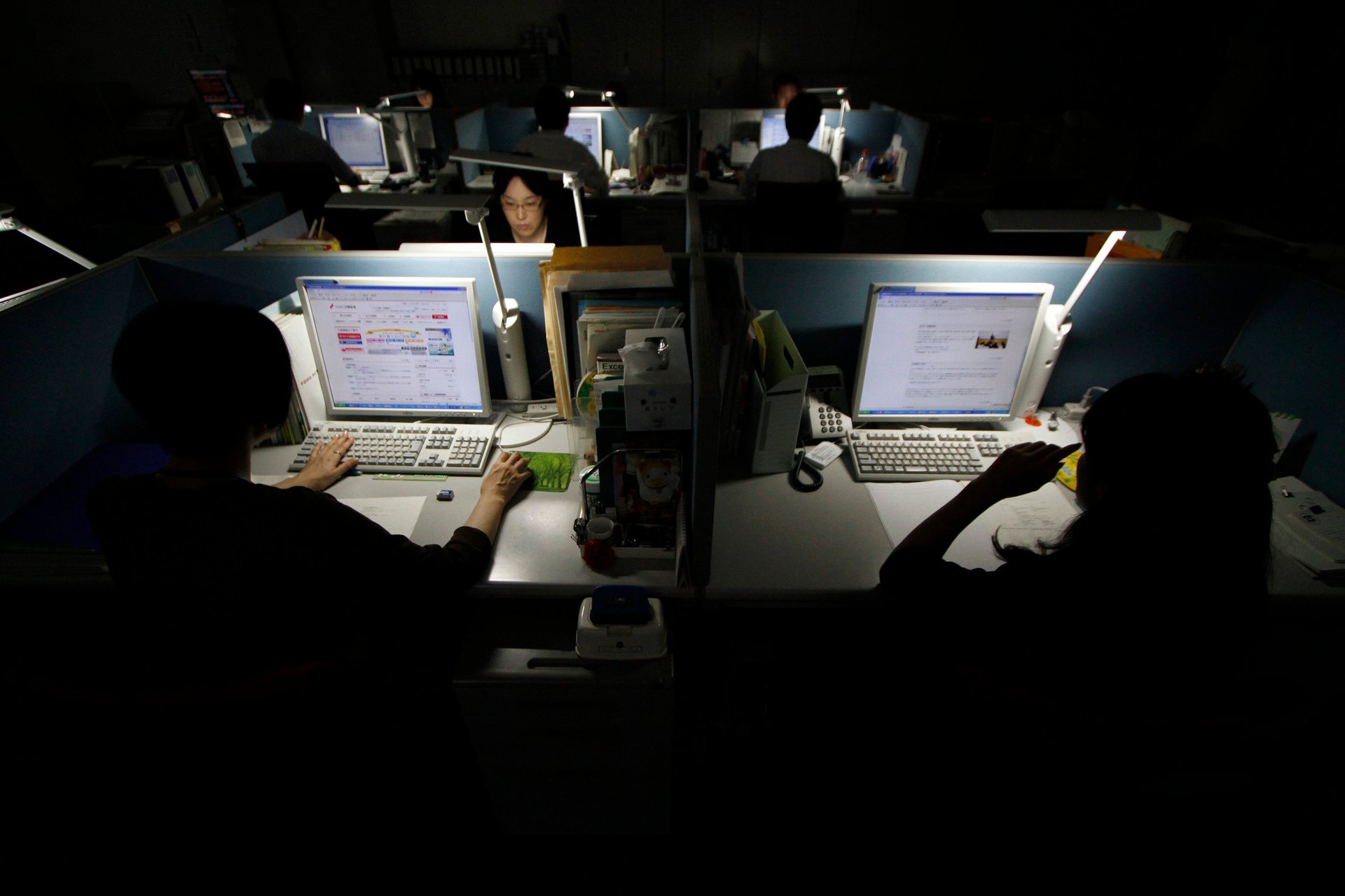

Then I came back to work, logged onto Slack and felt nauseous. My heart-rate spiked as I read through the company-wide, group, and individual messages, and I spent much of the first day unfocused and overwhelmed. Before my vacation, I’d thought of Slack conversations as time-consuming but amusing distractions. After, the multitude of online messages and personas felt like a destructive onslaught.

Returning to work after a vacation can be a shock to the system, and there are all manner of articles advising you on how to struggle through these back-to-work blues. One Huffington Post article offers “5 Smart Tips To Get Back On The Grind,” while The Guardian tells readers to “Stop dreaming about career changes,” and put aside goals of “twice-weekly gym sessions” while you’re at it. This perspective, though, portrays workplace misery as a negative experience that should be endured and suppressed, which misses the fundamental point: Back-to-work blues might be unpleasant, but they’re far from unreasonable. Workplace ennui is often an appropriate response to a difficult environment, and so deserves to be taken seriously. Rather than trying to ignore your misery and suppress your emotions into tolerating an unhappy job, it’s worth listening to your feelings of dissatisfaction and changing your work life instead.

This is not a novel attitude towards sadness, though it is one that’s often overlooked. More than a century ago, in 1904, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote about sadness as an emotional state that delivers change. “Why do you want to shut out of your life any agitation, any pain, any melancholy, since you really do not know what these states are working upon you?” he wrote in personal letters highlighted by the website Brainpickings. “Almost all our sadnesses are moments of tension that we find paralyzing because we no longer hear our surprised feelings living…we stand in the middle of a transition where we cannot remain standing.”

Sadness and other negative emotional states are a sign that something is wrong. Sometimes, of course, no amount of proactivity will solve whatever’s causing such sadness. But, where it’s within our power, we should take these emotions as a call to create change. In his 2008 book Against Happiness: In Praise of Melancholy, Eric G. Wilson argues that contemporary America’s infatuation with happiness has led society to underestimate the importance of melancholia. This is decidedly different from depression, which, Wilson says, creates a sense of apathy in response to uneasy anxiety. On the other hand, he writes, “melancholia (in my eyes) generates a deep feeling in regard to this same anxiety, a turbulence of heart that results in an active questioning of the status quo, a perpetual longing to create new ways of being and seeing.”

The dissatisfaction that comes from returning to work can throw you into this sort of melancholia, throwing light on the problems you’d become inured to over the days, weeks, and months of the daily grind. The shock of re-immersion can serve as a striking reminder that you have a miserable commute and need to take up cycling, that your most meaningful projects are have been perpetually sidelined for short-term distractions, or simply that you hate your job and deserve to think about a career change.

In my case, returning to Slack made me reconsider whether the benefits of easy incessant communication outweighed the costs. I saw how the convenient distraction of collegial Slack conversations followed me everywhere, and had utterly eradicated any line between work and home life. I decided to cut back, to leave more group messages unread, to make Slack-free days a regular occurrence rather than a rarity. This takes willpower and self-monitoring, which may fade as I get re-accustomed to office life, and so I also made the decision not to re-install Slack on my phone. (My editor agreed that cellphone Slack is completely unnecessary, as he can always text or call if something urgent comes up while I’m out of the office.)

I hope this change will help me stay focused, to spend concentrated time working on writing and research rather than constantly bouncing through distracting messages, and that, overall, it will help abate the anxiety that came with a return to work. If it doesn’t, though, I don’t intend to ignore my back-to-work blues. I plan to hold onto this fresh, questioning perspective for as long as possible. Even if it is a little melancholy.