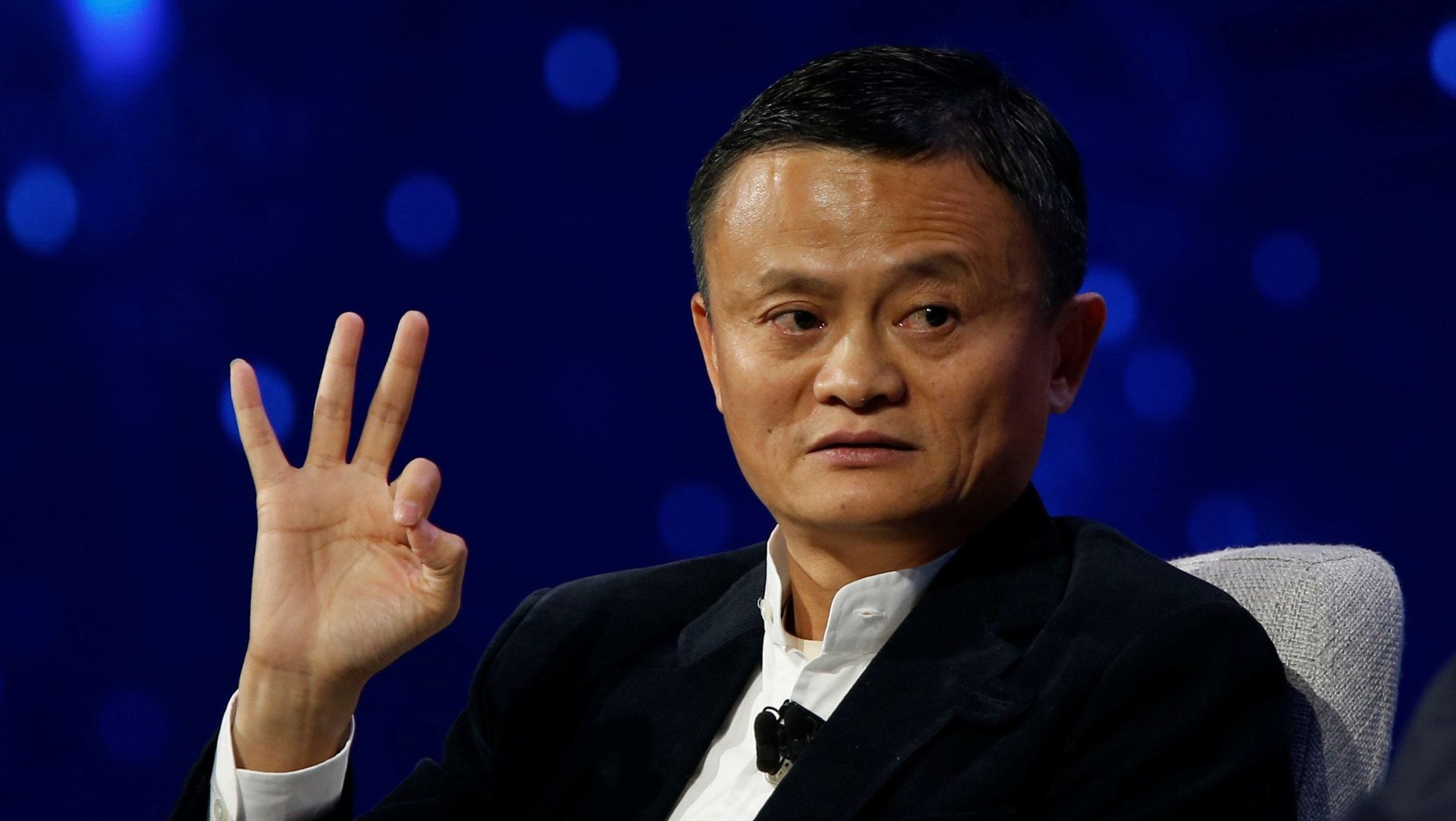

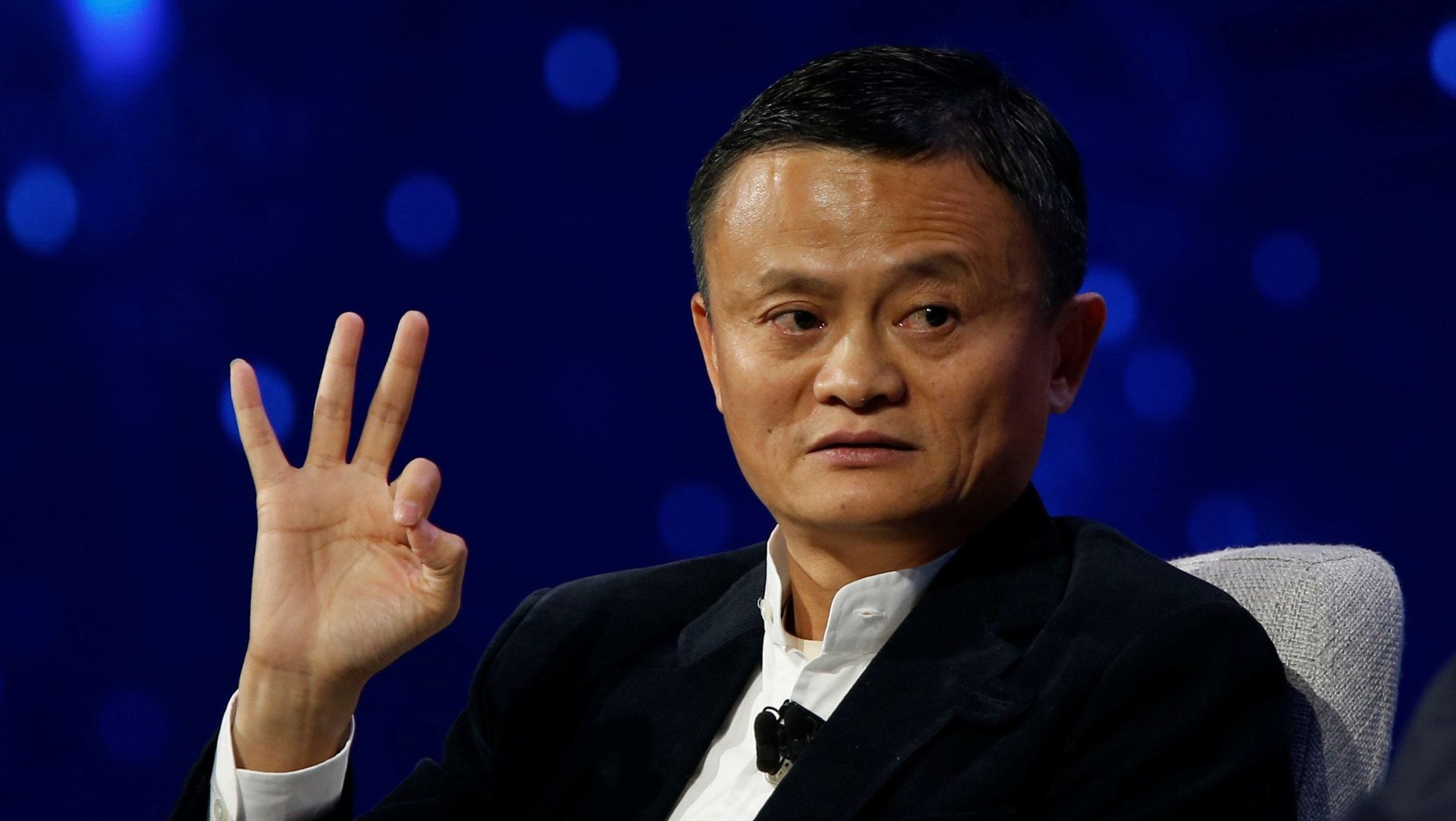

Jack Ma built Alibaba into a big family. He should now break it up into many smaller companies

Next September, as the e-commerce giant Alibaba marks its 20th birthday, its co-founder Jack Ma will hand over the reins as CEO of Asia’s most valuable company to a successor, Daniel Zhang.

Next September, as the e-commerce giant Alibaba marks its 20th birthday, its co-founder Jack Ma will hand over the reins as CEO of Asia’s most valuable company to a successor, Daniel Zhang.

Ma’s announcement that he will step down a year from now is surprising for two reasons.

First, it’s still early in the company’s history yet. Typically, founders of Asian companies stay on at the top of their firms for as along as possible.

Second, when succession plans have to be made, the heir to these Asian companies is usually a family member. Research has found that in countries with a poor institutional framework—inadequate shareholder protection and weak contract enforcement, for example—firms are more likely to be controlled by family members. Ma’s successor, Zhang, is not family.

Or is he?

Over its 19-year history, Alibaba has not had to rely on the family members of its co-founders. Ma launched his company out of his apartment in Zhejiang province, in the Yangtze River Delta area of eastern China, which was a relatively prosperous region with reasonably good economic institutions. A good institutional environment makes firm owners more willing to, for example, recruit professional managers and investors from outside the family without fear of having their property expropriated. But even though he has not relied on his literal family, Ma has long understood the importance of creating a robust family culture within Alibaba. From the beginning, he has treated a core group of top executives called the Alibaba Partnership (originally made up of 18 members, now 36) almost like family members. It’s understood that this small circle of senior executives can drop by Ma’s home for dinner anytime.

The partnership program, in which partners hold or are awarded “a meaningful level of equity interests” in the company, is an excellent and convenient way for Ma to reward his closest, most loyal associates and to motivate them to innovate relentlessly in order to make Alibaba bigger and better. The human resources challenge for any company is finding talented and loyal employees, and the organizational structure of a partnership, as a back-loaded reward system, can help attract employees who meet both criteria.

Fundamental to Ma’s success at Alibaba’s helm is his deep understanding of what motivates people and what keeps them entrepreneurial. He knows full well the importance of incentivizing himself and his followers with equity shares and control rights. After a bruising price war with eBay over the China market in the early 2000s, Ma sold a 40% stake in Alibaba to Yahoo for $1 billion in 2005.

But Ma was unhappy with the fact that he, the top executives, and his employees now held such a small combined stake in the company, and sought to buy back shares from Yahoo. When Yahoo refused, Ma in 2010 spun off a major Alibaba subsidiary, the online payments company Alipay, into a private company controlled by himself, causing an uproar as Yahoo accused Alibaba of having blindsided them. The bitter feud between the two companies eventually convinced Yahoo to sell half its stake back to Alibaba in 2012.

To cement his and the senior members’ control over the company, Ma created a dual-class share structure, which gave the partnership members superior voting rights in spite of a small combined stake in Alibaba. With greater control ownership and control over the company, Ma could count on his associates being loyal and motivated.

As companies grow bigger, however, there is a risk that its managers become less motivated. This is because share prices become a noisier measure of their performance, and also because the percentage of equity share they hold is getting smaller.

For more than two decades, one of the authors has been researching Chinese business and economics as a professor of economics and strategy. What has been uncovered is that while private enterprises in China have to navigate through imperfect institutional environments to survive, the key to their success is filling the voids left by the state, whether that’s a market niche where state-owned enterprises are absent, or incentive systems that help recruit and motivate people (again, something the state fails to provide).

In light of this, we propose a better plan for Alibaba. Instead of simply picking Zhang as the new CEO, Ma should do something much more drastic: break up Alibaba into a number of smaller companies.

Alibaba would then be a holding company owning a minority stake in all of the small companies, and each company would be headed by a small group of people each each holding a substantial amount of equity shares to motivate them. The key to sustained competitiveness in a fast-changing industry with cut-throat competition is constant innovation, and the best way to achieve this is by unleashing the entrepreneurial energy of the entire company. A collection of small companies held by Alibaba, each of which adopts the partnership system, will make this possible.

Business history tells us that it is hard for big companies to remain competitive. This is especially so when there is a great founder, like Ma, whose shoes are especially hard to fill.

Ma has made himself replaceable by grooming a close circle of trusted and capable top executives who he treats like family members. He is right in stepping aside to make room for a new generation of leaders. Now he needs to break Alibaba up into smaller companies to make it forever innovative and competitive.