One of Liberia’s fastest-rising CEOs is still learning to see his male privilege

Liberia has abundant natural resources, a geographically strategic port, and a relatively progressive government. But as of 2016, more than half of its population was living in poverty.

Liberia has abundant natural resources, a geographically strategic port, and a relatively progressive government. But as of 2016, more than half of its population was living in poverty.

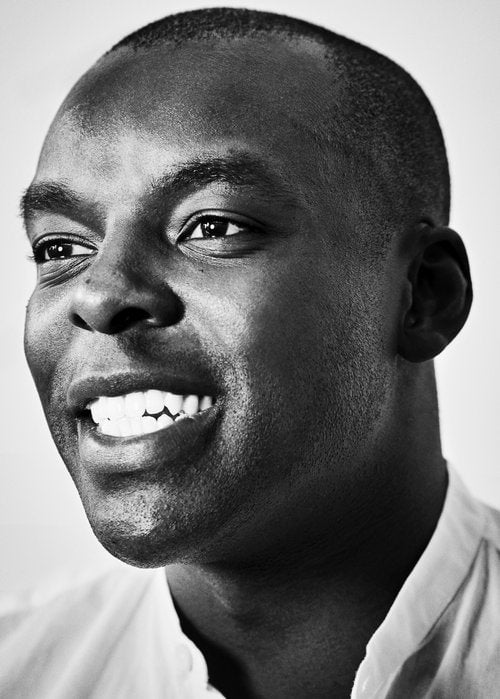

Chid Liberty, founder and CEO of ethical apparel manufacturer Liberty & Justice (L&J), is on a mission to upset the statistics.

He believes that rebuilding a nation begins with its women. ”What became clear, especially after a civil war, was that if we could get income into the hands of women, of mothers, then we would be able to touch so many different areas of impact from education to health to nutrition,” he said in a Q&A with Unreasonable.

Liberty, who was born in Liberia, lived in Germany as an infant when his father served as Liberia’s ambassador there; the family then moved to the US, while Liberia was engulfed in civil war.

Inspired by the work of 2011 Nobel Peace Prize winner Leymah Gbowee, who led the women’s peace crusade that helped end the second Liberian civil war that lasted from 1999 to 2003, Liberty returned to Africa and created L&J in 2009, raising about $3 million from US foundations and private investors to establish a Fair Trade Certified garment factory in Liberia. The enterprise provides work and educational opportunities for Liberian women vulnerable to unemployment and economic exclusion.

L&J supplies clothes and handbags to American labels like Prana and Haggar. Its own clothing label, Uniform, launched in 2016 and provides a Liberian child with a school uniform for every item sold. In 2017, the company started a Made in Africa initiative with a network of ethical factories clustered in Ghana, Liberia, and Benin.

Speaking with Quartz, Liberty explains why feminism isn’t necessarily about equal outcomes, how shame paralyzes men, and where even CEOs committed to elevating women can sometimes go wrong.

1. Did you actively think about workplace gender inequality prior to the Me Too movement? What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned from Me Too?

Though I definitely thought about inequality, I would put myself in the camp of men who didn’t quite understand how much gender, position, and power intersected in ways that left women feeling uncomfortable. Because I always focused on creating environments where women could thrive at work, I thought I was covered. However, there were things that came up that I didn’t fully realize how impactful they were for one, some, or all women on the team. Basically, I thought we always got the benefit of the doubt because of our intention on creating a good workplace for women. After really spending time listening, I realized that it’s still hard at times to see my male—and CEO—privilege, like it is for a fish to notice the water.

2. Do you identify as a feminist? Why or why not? How do you define your feminism?

I’ve identified as a feminist since college. To me feminism is all about equality; not of outcome but of opportunity.

3. What do you do on a daily basis to advance gender equality?

Well, my work is all about advancing gender equality through work and income opportunities for women. Quite selfishly, women are also where you get the biggest return on investment—but now the whole world is catching up on that insight.

4. What’s the biggest threat to men in America today? Why?

I don’t know, but it’s definitely not the Me Too movement. Having a president who thinks these things makes me want to puke in my mouth.

In my teenage years and 20s—and I know someone is reading this and thinking I was a mess all the way through meeting my wife—I can assure you that I did and said things that were so inappropriate that I couldn’t watch them on TV today without overwhelming shame. So, I think the biggest threat is likely shame. In many areas of life, men are struggling to see ourselves for who we have been to women throughout our lives.

5. Do you talk about sexism with your male peers? If so, what strategies prove most effective, and if not, what inhibits you from doing so?

Not enough. I hope that’s a sign about the men I work with. I think we all really go out of our way to hire and promote women. That said, we talk about why all co-founders and senior managers are men and what we can do about it. I think being blunt and fact-based has always helped these conversations. It’s always hard to argue with the truth.

6. What is your biggest anxiety about being a man?

These days, it’s just about being a great husband to Georgie and a great man for women to work with. I guess those are related in that I see my job as helping the people around me thrive.

7. What do you wish your female coworkers, and women at large, knew about you?

That I don’t see myself as more powerful than anyone. I know that might seem silly because I have a title that says that the buck stops with me. The title of CEO is more about responsibility to me than power.

I really see us all as equals trying to solve big problems. So if I screw something up, that’s probably where it’s coming from—I didn’t see it. I didn’t realize how different it is for me to make a joke versus another team member for whom there is less of a power disparity. But I am 100% open to seeing it, so holler at me at a time or in a way that it’s comfortable for you and I’m all ears and it will get better.

8. Some men feel like they can’t win: They’ll be criticized by men for speaking up, and by feminists for not speaking loud enough. What would you tell these men?

I don’t see this as a problem. Men generally know there’s an issue. I do feel like people can get a little extreme in demanding their rights—as they should. And so my biggest issue is moderating between the extreme (even if they are correct) and the more moderates (even if they are wrong in their moderate approach). That to me is the biggest struggle. We all know where we want to go and where we need to go. Some of us want to get there with the least amount of nastiness possible. That would be my camp.

9. If you could take back one thing you’ve said or done that contributed to bias at work or at home, what would it be? Why?

Definitely dating at work when there was a mismatch in power. I didn’t realize how much power plays into that scenario and I feel that many men, especially young managers, need to do some learning in this area. I think particularly where women are working to establish their careers or themselves in an industry, things that men see as harmless can actually be quite harmful. I think we all owe it to women to be able to be at work without having to worry or feel any type of anxiety about their love life and how it might affect their work. I feel like that actually solves so many problems for men, too—knowing super clearly that it’s just a horrible idea, that’s not going to work out, so no need to make comments, jokes, or any unwanted anything.

10. What’s the best advice you’ve received from another man, and what’s your best advice for young men today?

As someone who tends to really like the people I work with, I would just tell young men that work is a special relationship. It’s not family, it’s not friends, it’s its own thing.

I think I came out of an era in tech where you were encouraged to bring your “whole self” to work. I would say that we should dial that back a bit and just bring your work self to work. There are certain boundaries that just shouldn’t be crossed. I think when that’s established, I would say that without a doubt, some of the most fulfilling, unexpected, ridiculously productive relationships you have at work will be with women.