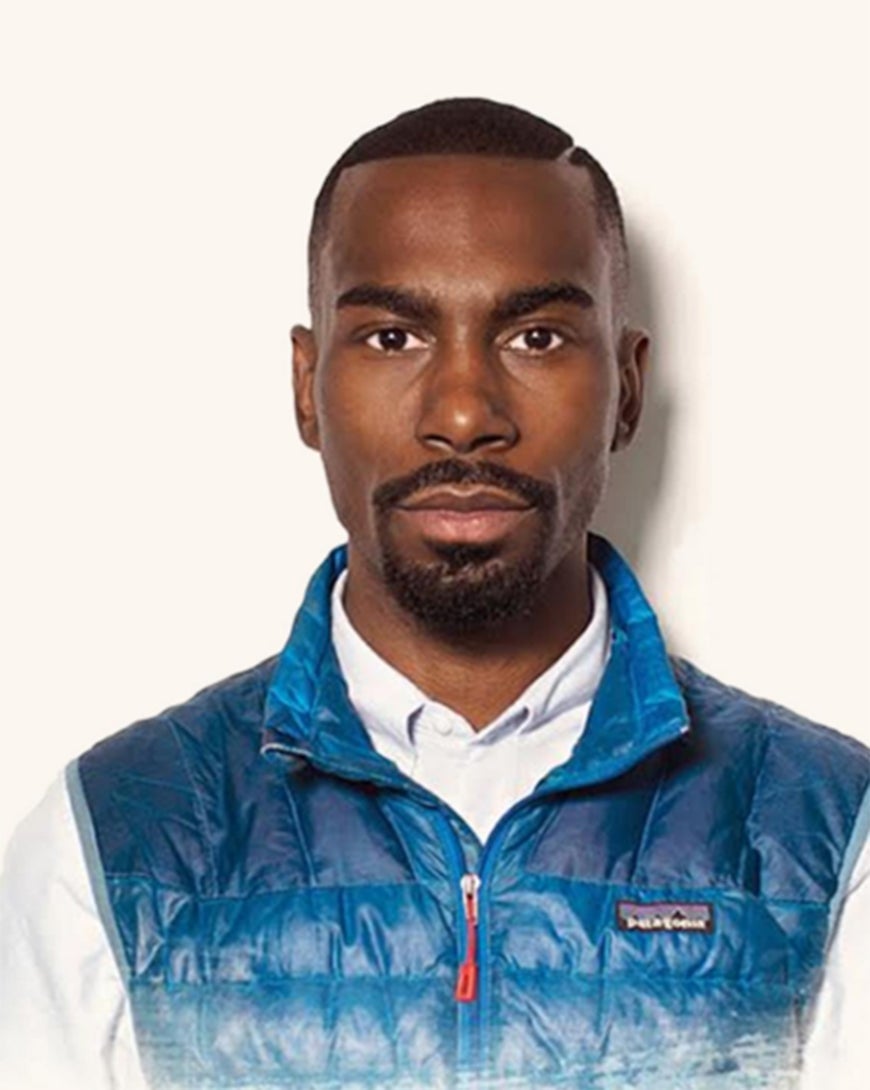

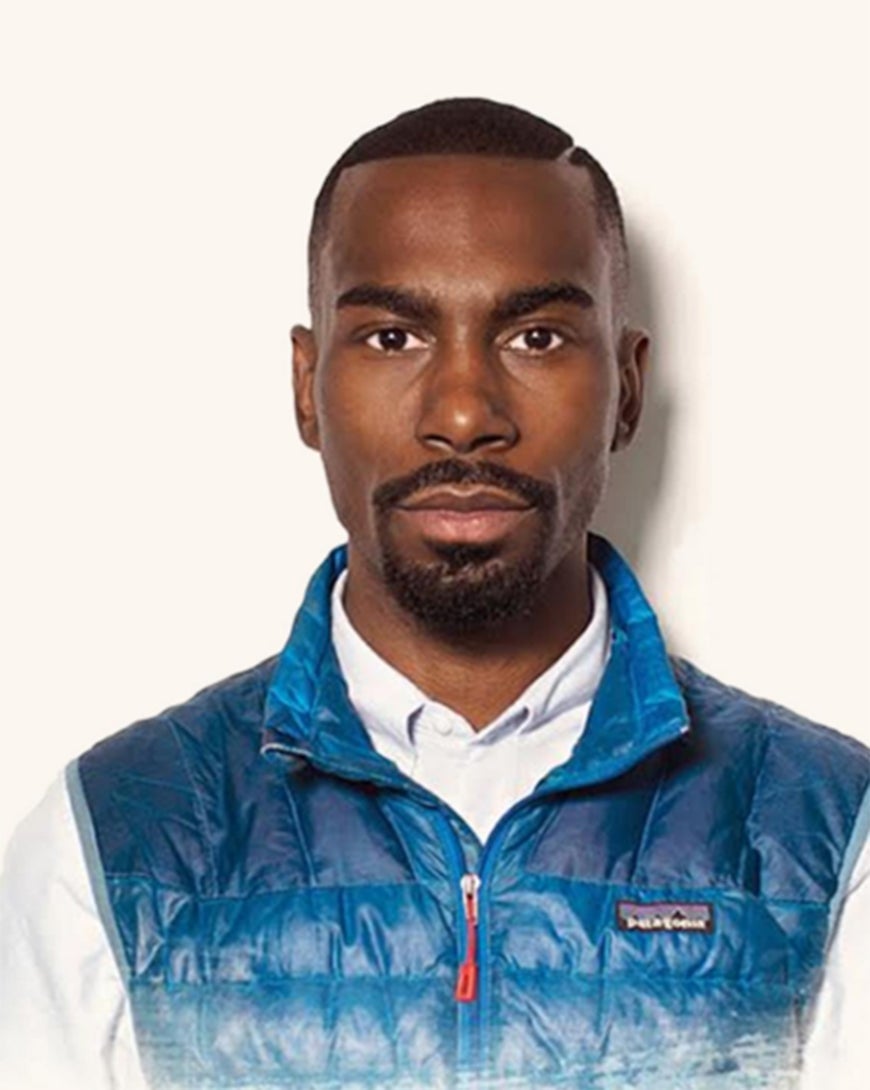

Activist DeRay McKesson on men who misunderstand feminism: “We don’t lose anything when we are all free”

Few 21st century American activists are more iconic than DeRay McKesson.

Few 21st century American activists are more iconic than DeRay McKesson.

Four years ago, McKesson’s life looked different. He was working as a school administrator in Minneapolis, but he was glued to news reports of the protests in Ferguson, Missouri in the wake of the police’s killing of Michael Brown, McKesson tells Vice. He planned to visit Ferguson to take part in the protests. That weekend trip ended up transforming his life—soon after, he quit his job and devoted his life to activism on behalf of racial justice.

Today, McKesson, 33, is one of the leaders of the Black Lives Matter Movement. He’s a co-host of the podcast Pod Save The People, exploring racial justice and American politics. He’s also the co-founder of Campaign Zero, a policy platform to end police brutality, and author of On the Other Side of Freedom: The Case for Hope, a memoir on his life thus far as an educator and activist. He has been sued twice by American police officers over his involvement in the 2016 Black Lives Matter protests in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. That year he also met with Barack Obama at the White House to discuss law enforcement’s relationship with black communities. And he’s cultivated a Twitter presence so prolific it is reportedly monitored by the US Department of Homeland Security.

“If the promise of the country is that people can live in their gifts, then what you see right now is that there are a lot of people who can’t access those gifts at all because they can’t eat, they don’t have anywhere to sleep, they’re in jail for things that make no sense, they’re in a criminal justice system that isn’t about rehabilitation and growth, that’s just about punishment,” McKesson recently argued in an interview with Vice.

In this interview, McKesson talks with Quartz about his definition of feminism, the best advice he’s received, and the best advice he has for young men today.

1. Did you actively think about workplace gender inequality prior to the Me Too movement?

Yes, I was most recently the chief of human capital for Baltimore City Public Schools, an organization with [nearly] 11,000 staff members and 20,000 subscribers on our health insurance plans. We were always proactively designing systems to address equity in all parts of the employment process: setting salaries, conducting salary reviews, developing interview processes, and employee feedback, evaluations and discipline.

2. Do you identify as a feminist? Why or why not? How do you define your feminism?

Yes, I do. Feminism is the acknowledgement that systems and structures disadvantage and marginalize women, especially women of color, in specific ways, coupled with the belief that is our collective responsibility to advocate for and demand that women are able to participate and experience all aspects of society in ways that are rooted in justice, equity, and equality.

3. What do you do on a daily basis to advance gender equality?

I aim to be mindful of how I use my platforms to listen to the voices of women, to create and support spaces where other voices can be heard, and to amplify and advocate as an ally.

4. What’s the biggest threat to men in America today? Why?

Men, on the whole, are not under siege in America. That said, black men experience systemic disparities in the criminal justice system in ways that are so broad in scope that it is hard to believe sometimes.

5. Do you talk about sexism with your male peers?

If so, what strategies prove most effective, and if not, what’s your biggest inhibition to doing so?

I do. I’ve found it helpful to ask men to think about times when they’ve felt unsafe and then have them think about times when they think women feel unsafe, or other people from identities that they don’t share. Safety is an interesting nexus that most people can understand. And in these conversations, I’ve had men, especially straight men, realize that they almost never think about their own safety because of the way society is set up.

6. What is your biggest anxiety about being a man?

Being killed by the police, being seen as a threat simply for existing, and homophobia and its manifestations.

7. What do you wish your female co-workers, and women at large, knew about you?

I wish that we spoke more about the ways that both men and women participate in and perpetuate homophobia. In the public conversation, homophobia is always seen as physical violence or overt verbal violence but rarely portrayed in the more subtle ways that it shows up in day-to-day life.

8. Some men feel like they can’t win: They’ll be criticized by men for speaking up, and by feminists for not speaking loud enough. What would you tell these men?

We will all win when we’ve achieved gender equity. Keep doing the work.

9. If you could take back one thing you’ve said or done that contributed to bias at work, or at home, what would it be? Why?

I was slow to understand bias in the hiring process, as it often manifests more subtly than you’d think—with women accepting “final” offers sooner than men, etc. So, I had to rethink our offer strategy to account for these differences so that women were not being shortchanged.

10. What’s the best advice you’ve received from another man, and what’s your best advice for young men today?

The best advice I’ve received is that we don’t lose anything when we are all free. And the advice I’d give to young men is to remember that because you hadn’t lived the experience doesn’t mean that it isn’t valid.