Estimates of job loss due to automation miss one big factor

Predicting the scale of AI-induced job losses has become a cottage industry for economists and consulting firms the world over. Depending on which model one uses, estimates range from terrifying to totally not a problem.

Predicting the scale of AI-induced job losses has become a cottage industry for economists and consulting firms the world over. Depending on which model one uses, estimates range from terrifying to totally not a problem.

Since 2013, the most cited predictions include a study from Oxford University that predicted 47% of US jobs could be automated within the next decade or two; an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report that suggested just 9% of jobs in the United States were at high risk of automation; PwC research that found 38% of jobs in the United States were at high risk of automation by the early 2030s; and a McKinsey report that found around 50% of work tasks around the world are already automatable.

A lot of this difference can be explained by the methodology of these studies. Looking at whether an entire occupation can be automated is a different question than whether tasks within that occupation can be automated.

I favor the PwC high-end estimate of 38%, which used the task-based approach.

But I believe using only the task-based approach misses an entirely separate category of potential job losses: industry-wide disruptions due to new AI-empowered business models. Separate from the occupation- or task-based approach, I’ll call this the industry-based approach.

Part of this difference in vision can be attributed to professional background. Many of the preceding studies were done by economists, whereas I am a technologist and early-stage investor. In predicting what jobs were at risk of automation, economists looked at what tasks a person completed while going about their job and asked whether a machine would be able to complete those same tasks. In other words, the task-based approach asked how possible it was to do a one-to-one replacement of a machine for a human worker.

My background trains me to approach the problem differently. Early in my career, I worked on turning cutting-edge AI technologies into useful products, and as a venture capitalist I fund and help build new startups. That work helps me see AI as forming two distinct threats to jobs: one-to-one replacements and ground-up disruptions.

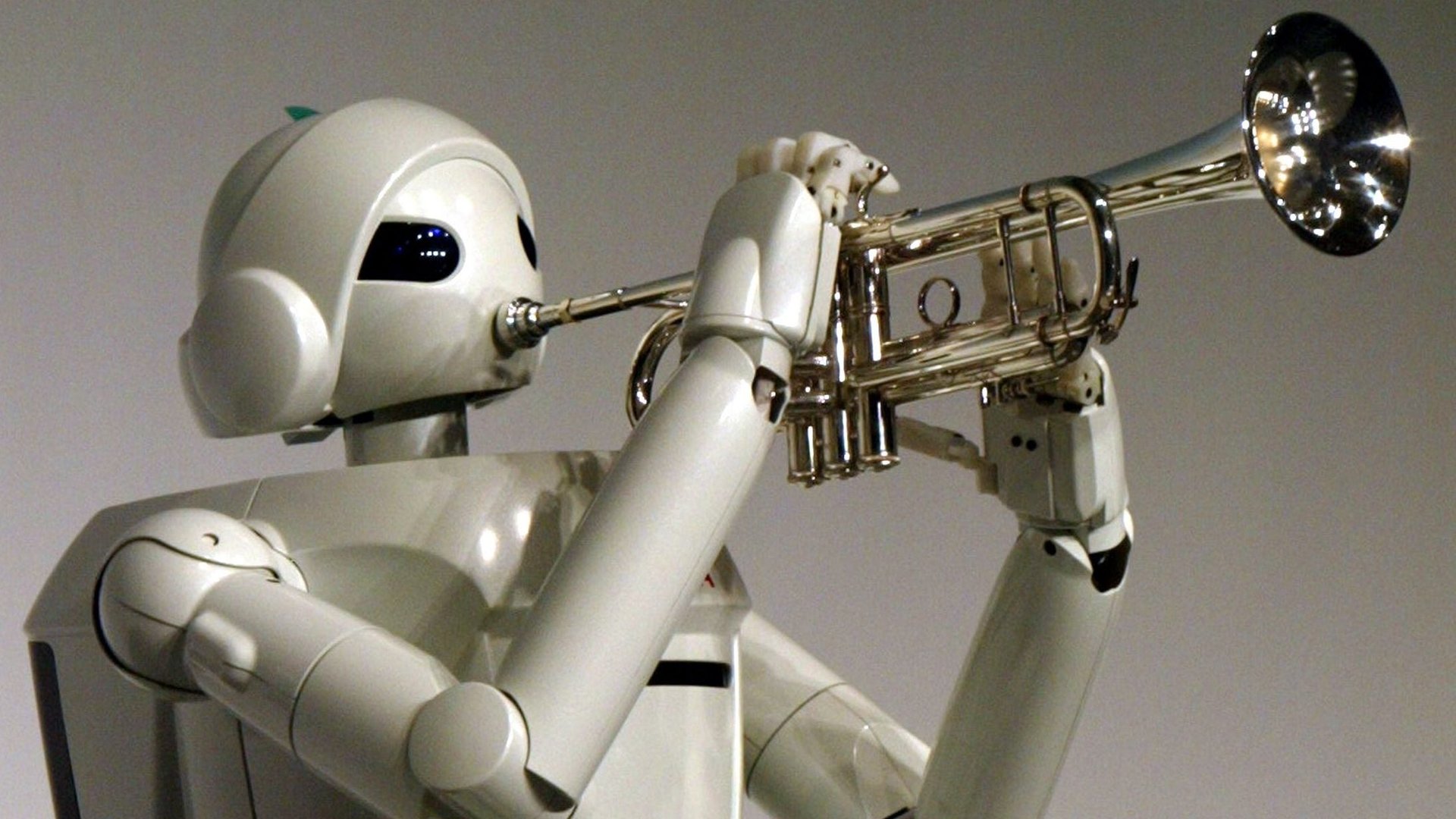

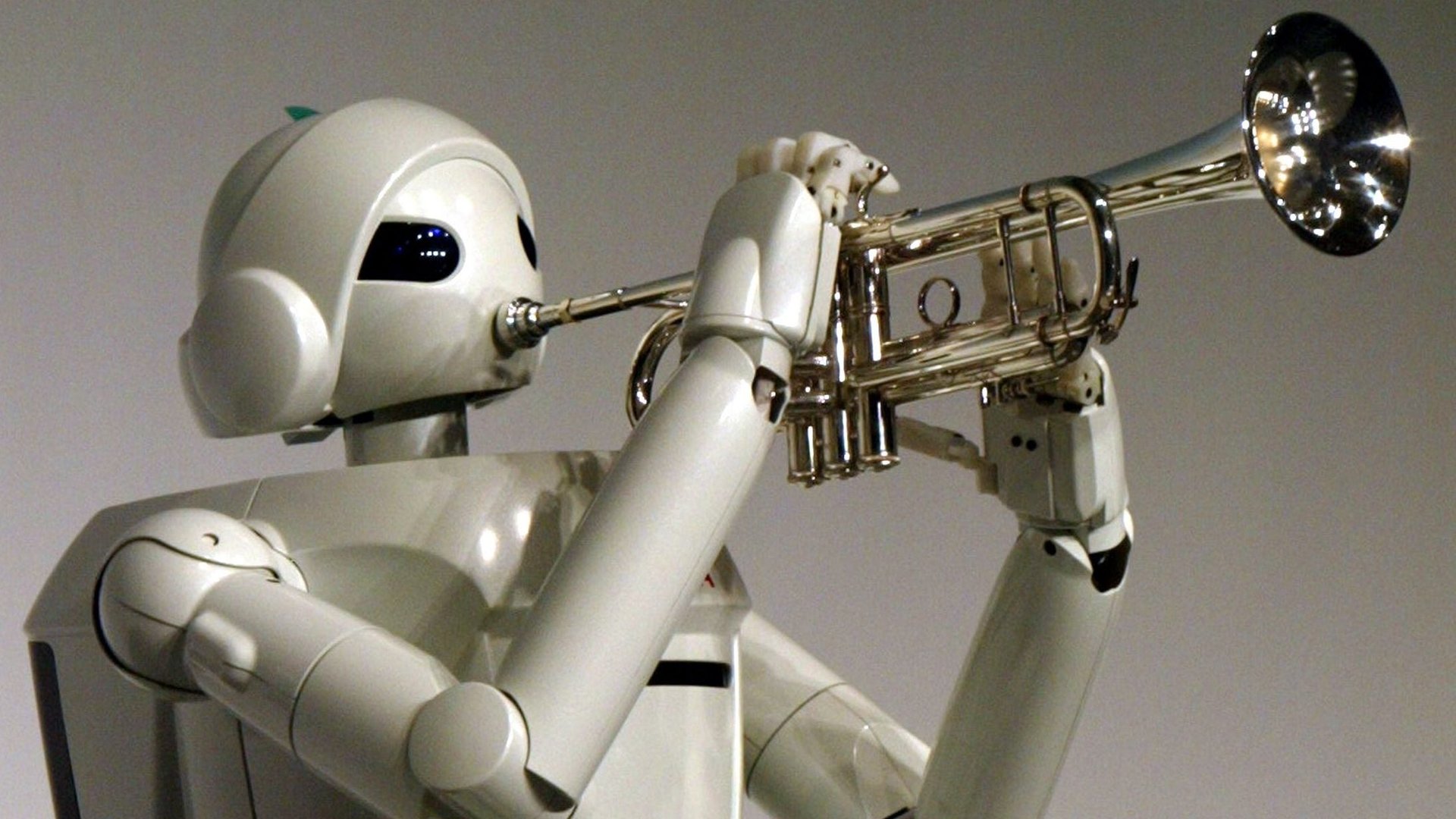

Many of the AI companies I’ve invested in are looking to build a single AI-driven product that can replace a specific kind of worker—for instance, a robot that can do the lifting and carrying of a warehouse employee or an autonomous-vehicle algorithm that can complete the core tasks of a taxi driver. If successful, these companies will end up selling their products to companies, many of whom may lay off redundant workers as a result. These types of one-to-one replacements are exactly the job losses captured by economists using the task-based approach, and I take PwC’s 38% estimate as a reasonable guess for this category.

But then there exists a completely different breed of AI startups: those that reimagine an industry from the ground up. These companies don’t look to replace one human worker with one tailor-made robot that can handle the same tasks; rather, they look for new ways to satisfy the fundamental human need driving the industry.

Startups like Smart Finance (the AI-driven lender that employs no human loan officers), the employee-free F5 Future Store (a Chinese startup that creates a shopping experience comparable to the Amazon Go supermarket), or Toutiao (the algorithmic news app that employs no editors) are prime examples of these types of companies. Algorithms aren’t displacing human workers at these companies, simply because the humans were never there to begin with. But as the lower costs and superior services of these companies drive gains to market share, they will apply pressure to their employee-heavy rivals. Those companies will be forced to adapt from the ground up— restructuring their workflows to leverage AI and reduce employees —or risk going out of business. Either way, the end result is the same: there will be fewer workers.

This type of AI-induced job loss is largely missing from the task-based estimates of the economists. If one applied the task-based approach to measuring the automatability of an editor at a news app, you would find dozens of tasks that can’t be performed by machines. They can’t read and understand news and feature articles, subjectively assess appropriateness for a particular app’s audience, or communicate with reporters and other editors. But when Toutiao’s founders built the app, they didn’t look for an algorithm that could perform all of the above tasks. Instead, they reimagined how a news app could perform its core function—curate a feed of news stories that users want to read—and then did that by employing an AI algorithm.

I estimate this kind of from-the-ground-up disruption will affect about 10% of the workforce in the United States. The hardest-hit industries will be those that involve high volumes of routine optimization work paired with external marketing or customer service: fast food, financial services, security, even radiology. These changes will eat away at employment in the “Human Veneer” quadrant of the earlier chart, with companies consolidating customer interaction tasks into a handful of employees, while algorithms do most of the grunt work behind the scenes. The result will be steep—though not total—reductions in jobs in these fields.

Putting together percentages for the two types of automatability—38% from one-to-one replacements and about 10% from ground-up disruption—we are faced with a monumental challenge. Within ten to twenty years, I estimate we will be technically capable of automating 40% to 50% of jobs in the United States.

This—and I cannot stress this enough—does not mean the country will be facing a 40% to 50% unemployment rate. Social frictions, regulatory restrictions, and plain old inertia will greatly slow down the actual rate of job losses. Plus, there will also be new jobs created along the way, positions that can offset a portion of these AI-induced losses, something that I explore in coming chapters. These could cut actual AI-induced net unemployment in half, to between 20% and 25%, or drive it even lower, down to just 10% to 20%.

This article has been adapted from AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order.