Fashion’s big diversity problem goes way beyond the models

Talk of diversity in fashion usually focuses on the outward-facing stuff: The people featured on runways, magazine covers, and ad campaigns. There’s good reason for that. Models are the visible faces of brands. Customers are demanding that the brands they support reflect their own diversity, and that pressure has helped.

Talk of diversity in fashion usually focuses on the outward-facing stuff: The people featured on runways, magazine covers, and ad campaigns. There’s good reason for that. Models are the visible faces of brands. Customers are demanding that the brands they support reflect their own diversity, and that pressure has helped.

But it’s one slice of a much bigger system. In a Jan. 7 report, the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), the leading trade association for American fashion, and PVH Corp., owner of the Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger brands, called out the lack of diversity in fashion across all levels of its workforce, from the entry level to the boardroom, where the power is concentrated. It says the result is a self-perpetuating imbalance in fashion’s corporate culture, where those in power retain power while minority groups struggle to access the upper ranks.

To illustrate the issue, the CFDA and PVH explain the difference between “inclusivity” and “diversity.” Diversity is the “measure of difference” in a workplace. Inclusion, on the other hand, describes a climate where people of all types feel comfortable expressing themselves, creating a scenario where everyone is able to contribute their best work.

“It is often assumed that diversity is enough,” the report says. “However, without inclusion, diversity is ineffective. Leaders are prone to struggling with inclusion as it is often a learned skill. Even in organizations with the best intentions, diversity and inclusion leadership development is often siloed instead of being integrated in other leadership skill-training.”

Diversity isn’t just about race, either. It encompasses differences in abilities, age, gender, and sexual orientation.

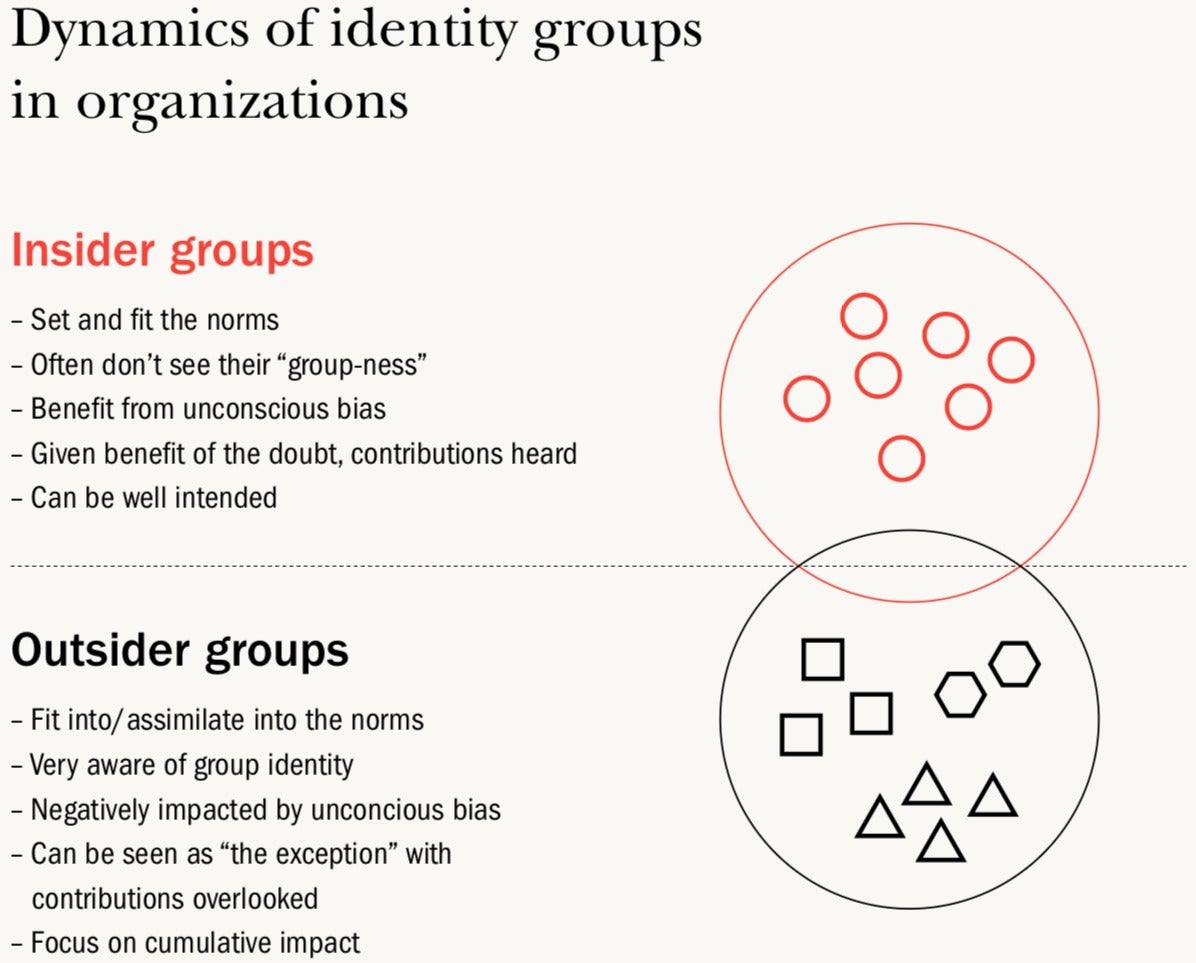

The CFDA and PVH say the uneven power dynamics create “insider” and “outsider” groups in fashion’s workplaces. The insider group is the one with more systemic power, and though it doesn’t say so explicitly, it suggests white men, unsurprisingly, hold much of this power. (Even the fashion industry, which is propped up by women and their spending, is largely run by men.) This insider group may not even recognize itself as a “group,” but nonetheless, it sets the norms.

“Outsider” minority groups have to fit into the norms set by the insiders, and are more aware of themselves as a group. They can find it harder to assert their positions, which means their perspectives, “which are often central to creativity and innovation,” the report notes, can be lost. Unconscious biases maintain and reinforce these dynamics.

“There is a lack of opportunity and access for people of underrepresented backgrounds in the fashion industry,” Erica Lovett, Condé Nast’s inclusion and community manager, is quoted saying in the report. “It’s a systemic issue tied to the homogeneity of industry leadership.”

The CFDA and PVH don’t offer specific solutions. The aim is more to get individual companies thinking and coming up with their own solutions. The CFDA is also planning a series of projects to promote inclusion in the industry.

Steven Kolb, CEO of the CFDA, told Business of Fashion that it can’t force brands to change, but what it can do is “make sure we’re talking about it and the industry is listening and participating.” It’s a step in the right direction.