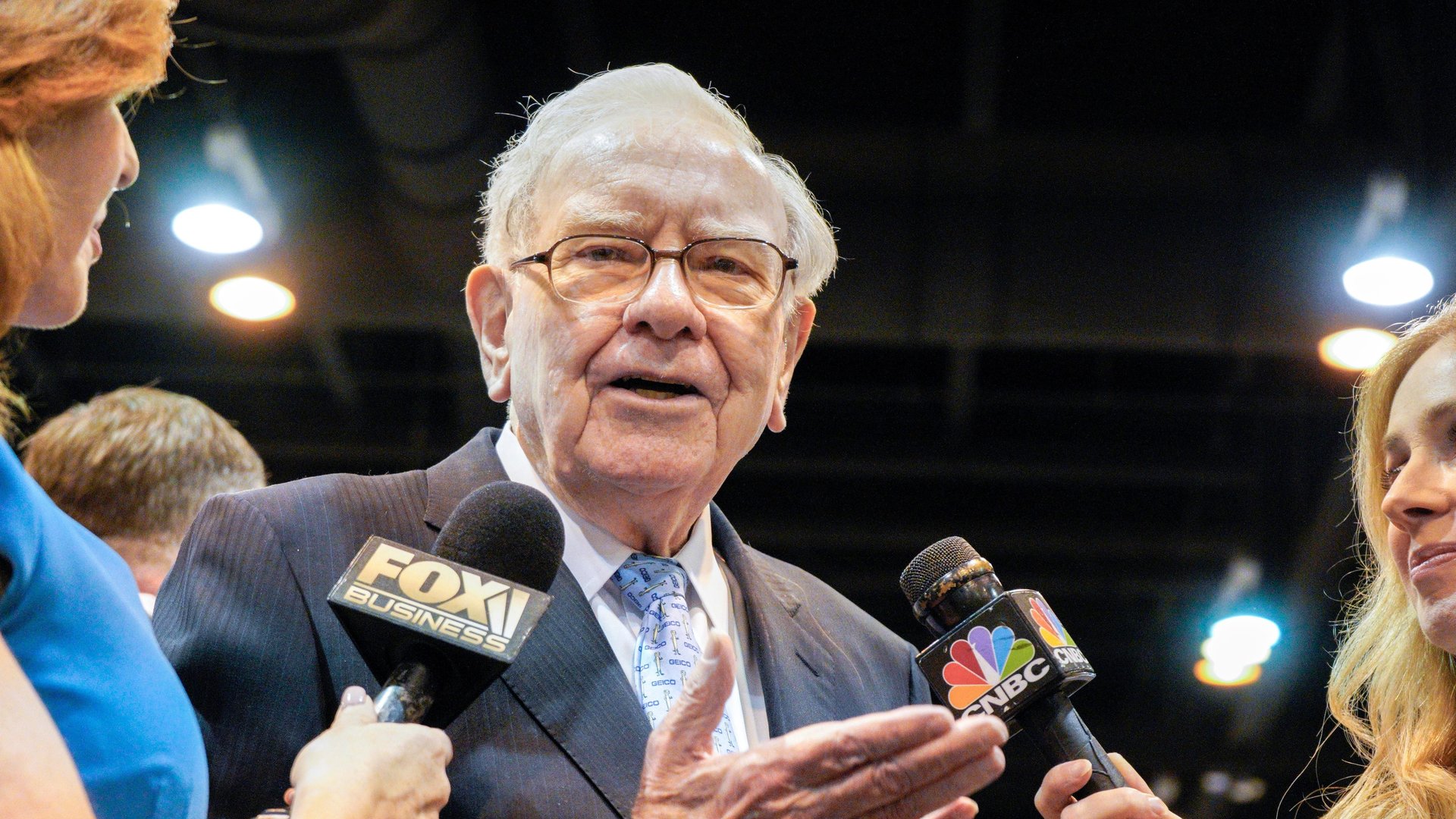

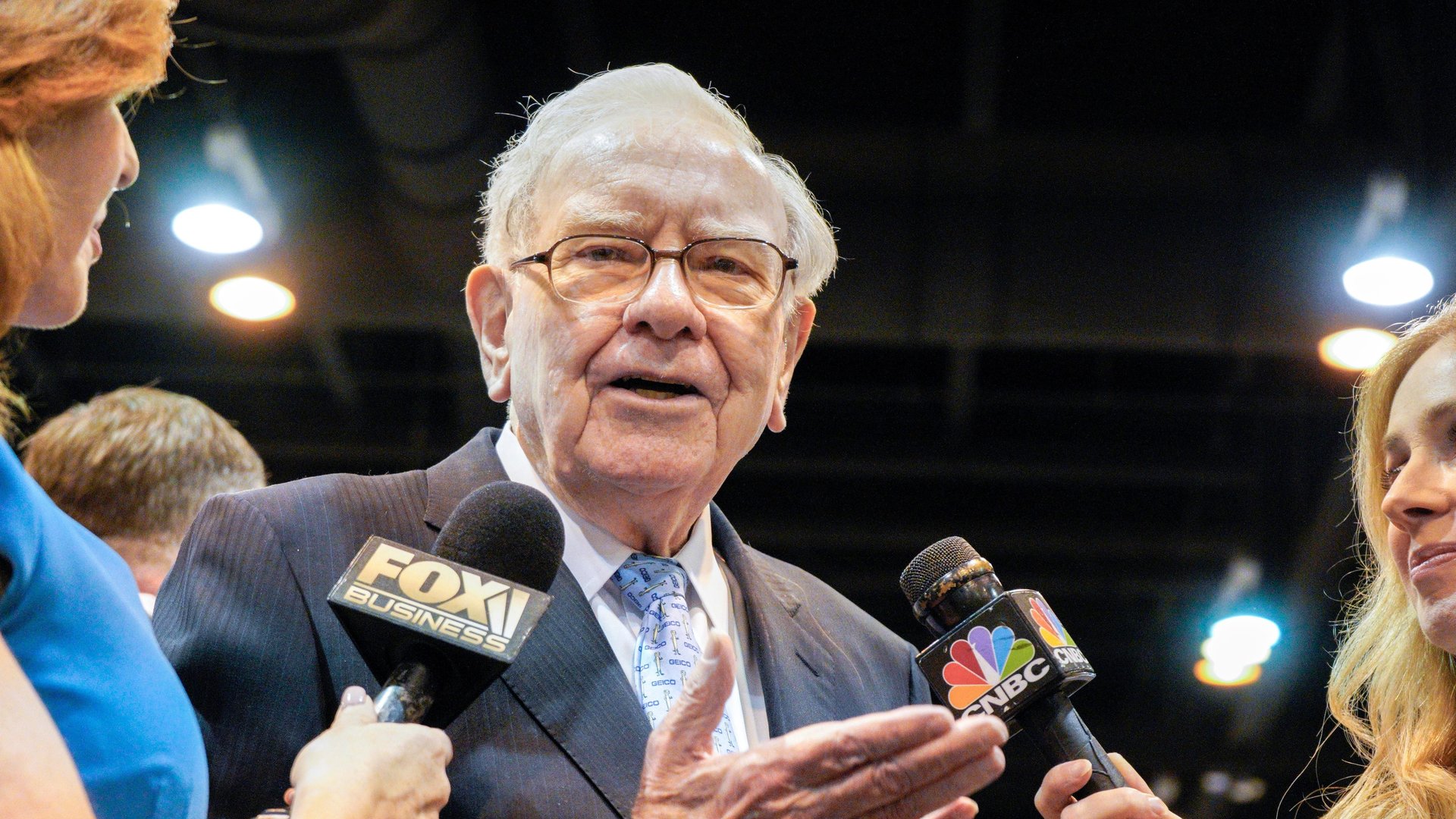

Warren Buffett on the dangers of the quarterly “number”

One of Berkshire Hathaway’s quirks is that the Omaha-based conglomerate has no company-wide budget (though many of the businesses it owns maintain their own). Berkshire subsidiaries are never required to submit budgets or forecasts to the central office. Chairman Warren Buffett has long practiced a decentralized management style in which the managers of subsidiary businesses are largely left to run their companies as they see fit.

One of Berkshire Hathaway’s quirks is that the Omaha-based conglomerate has no company-wide budget (though many of the businesses it owns maintain their own). Berkshire subsidiaries are never required to submit budgets or forecasts to the central office. Chairman Warren Buffett has long practiced a decentralized management style in which the managers of subsidiary businesses are largely left to run their companies as they see fit.

The absence of a company-wide quarterly target isn’t just for simplicity’s sake, Buffett explained in his annual letter (pdf) released Saturday. It’s also a way to reinforce the company’s emphasis on ethics.

“Shunning the use of this bogey [the quarterly target] sends an important message to our many managers, reinforcing the culture we prize,” Buffett wrote. He went on:

Over the years, Charlie [Munger] and I have seen all sorts of bad corporate behavior, both accounting and operational, induced by the desire of management to meet Wall Street expectations. What starts as an “innocent” fudge in order to not disappoint “the Street”—say, trade-loading at quarter-end, turning a blind eye to rising insurance losses, or drawing down a “cookie-jar” reserve—can become the first step toward full-fledged fraud. Playing with the numbers “just this once” may well be the CEO’s intent; it’s seldom the end result. And if it’s okay for the boss to cheat a little, it’s easy for subordinates to rationalize similar behavior.

Buffett has spoken out against companies incentivizing such behavior before. At the last Berkshire shareholder meeting in May, he said Wells Fargo committed the “cardinal sin” of ignoring the perverse incentives that encouraged workers to lie, manipulate numbers, and even open phony accounts to meet unrealistic targets. (It was a sin for which the Oracle of Omaha forgave them: He also said he has no plans to reduce Berkshire’s 10% stake in the company.)

Keeping bureaucracy to a minimum, as famously frugal Berkshire does, is one way to discourage such actions, Buffett and Munger have said.

“Think how poorly all of us have behaved in huge bureaucracies, because we couldn’t change anything,” Munger said earlier this month at the annual meeting of the Daily Journal Corporation, a publishing and technology company he chairs. For a company, “having no bureaucracy is a huge advantage—if the people who are running it are sensible people.”