Life coaches are the new personal trainer

Life coaches’ careers are taking off. The occupation, which hardly existed a few years ago, has now become indispensable to the careers of everyone from Oprah Winfrey and members of the (formerly wildly dysfunctional) Metallica, to average professionals trying to improve their lot.

Life coaches’ careers are taking off. The occupation, which hardly existed a few years ago, has now become indispensable to the careers of everyone from Oprah Winfrey and members of the (formerly wildly dysfunctional) Metallica, to average professionals trying to improve their lot.

While the US Bureau of Labor Statistics does not collect data on life coaches just yet (it groups them with other types of trainers and counselors), the International Coach Federation estimates (pdf, p. 8) that there are now 17,500 coaches (outside of sports) working in North America alone as of 2015. Working with a mix of business and private clients, they earned an average income of $61,900—nearly twice the US median annual wage.

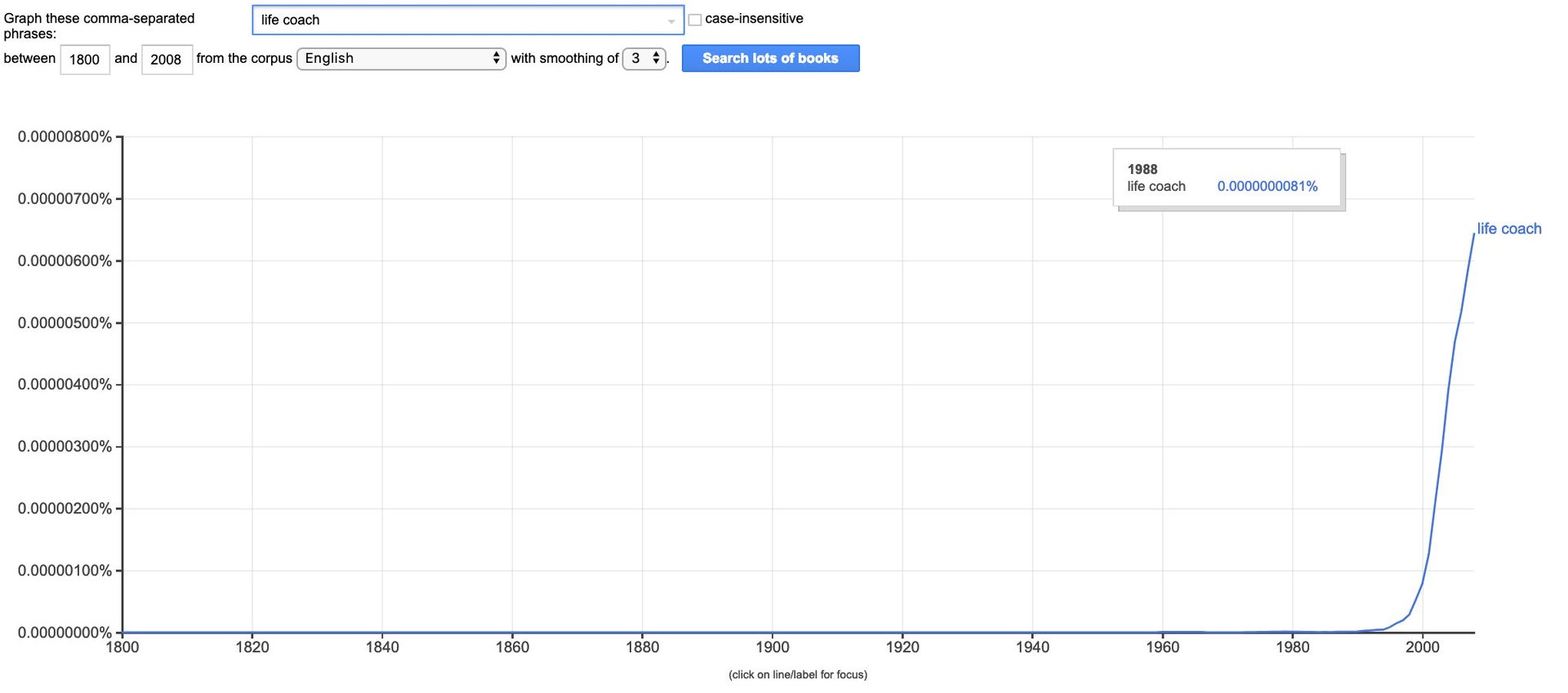

Since the late 1980s, Google’s Ngram index shows the mention of life coaches growing exponentially.

Life coaches help their clients identify goals, remove barriers, and encourage regular progress for days or years. Most clients, according to the ICF (pdf), are managers who use coaches to help them in their career, but the number of clients using coaches in their personal life is growing as well. Thumbtack, a marketplace to hire local professionals from plumbers to tutors, says life coaches are among its fastest-growing categories, increasing by more than 60% each year. Today the platform has about 5,000 active life coaches, who charge an average of $70 to $90. per session.

Personal trainers were once obscure too

US Census data is an archeological dig for data on evolving occupations. Some fields, such as fabric menders and mine-car operators, have faded, while new categories, what economists like David Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology call “frontier jobs” for people working on the edge of emerging technologies, are growing fast. Frontier-job categories included “word-processing supervisor” in the 1980s and “robotic machine operator” a decade later, and then “chief information officer” and “programmer-analyst” in 2000. Today, the frontier is full of data scientists. The job didn’t exist a decade ago, but the US government now counts 35,000 practitioners in the field who earn a median base salary of more than $110,000.

Life coaches belong in another category: “wealth work,” Autor calls it. After people satisfy their basic and material needs, many migrate up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs toward “esteem” and finally “self-actualization.” These jobs tend to serve those desires.

That’s reflected in a workforce which has given us lifestyle occupations such as professional gift wrappers and fingernail formers (officially added to the US government’s list of job categories in the 1980s and 1990s, respectively), oyster preparers (2000), sommeliers (2010), and, of course, personal trainers. Such jobs may have existed in some form before, but the Census only began tracking them after their popularity soared. Personal trainers, for example, were not classified before 2000. Today, more than 300,000 Americans are fitness trainers.

But people are not just “self-actualizing” physically. Psychological well-being is just as popular a pursuit. In recent decades, hypnotherapists, marriage and family counselors, and employee wellness coordinators all emerged as occupations with enough practitioners to be counted under Census guidelines.

As demand for routine manual human labor declines (it has fallen steadily every year since 2008), more than 91% of new jobs in the coming years will be in the services sector, Thumbtack says, citing BLS forecasts. Life coaches, it seems, will be among them.