The surprising benefits of singing at work

Every Wednesday at lunchtime, Judy Rose takes a break from her job as chief operations officer at Triodos, an “ethical bank” based in Bristol in the west of England, to spend an hour harmonizing with colleagues.

Every Wednesday at lunchtime, Judy Rose takes a break from her job as chief operations officer at Triodos, an “ethical bank” based in Bristol in the west of England, to spend an hour harmonizing with colleagues.

Rose leads a workplace choir that’s brought together colleagues from finance to marketing and HR since 2017. They gather in a light-filled room with a view of a distant harbor and grassy slopes, that’s also opposite the large windows of the canteen, from which amused coworkers watch the singers belt out “Down To The River To Pray.” The choir doesn’t mind: It’s sung in all-staff meetings before now—once, memorably, to illustrate a wider point about workplace harmony. They’re not shy about the delight they taking in singing at work.

Practicing a musical instrument at work and singing in workplace choirs have become so popular in UK offices that they’ve sparked television shows, local choir leagues, and national competitions. These have in turn stoked passions for singing that previously had no outlet, bringing together workplace singing groups that have then continued to practice, gig, and fundraise. An increasing focus on “wellbeing” at work, meanwhile, has led some of the UK’s biggest corporations to fund music lessons and choirs.

The goals of those who want to bring more music to the workplace are lofty: to foster a cohesive workforce and thereby promote staff happiness, loyalty, and productivity. Ultimately, they say, they want to bring transcendence to the office.

Humming at the coffee machine

Rose was inspired to start the Triodos choir with two colleagues after the company held a “wellbeing week” in which co-workers went running together, practiced yoga—and experimented with choral song. Rose played the trombone as a child and still loves music, but her busy day job didn’t leave much space for singing—or socializing—until she became the choir’s de facto musical director.

“It’s a really nice way for me to engage with people I wouldn’t normally spend time with,” Rose says, adding that it makes her happy to know colleagues have enjoyed learning a song and then “hearing people humming it at the coffee machine.” Singing takes people out of their comfort zone, but once they’ve made the leap, Rose thinks it helps build self-assurance. It “gives confidence, a feeling of achievement—and fun,” Rose said. “We’re not a very strict choir…There’s a lot of laughing.”

There have been efforts to document the benefits of singing at work. Claudia Röhlen was studying gender and diversity at Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences in northern Germany when she became fascinated by the power of ensemble singing. For her thesis, she conducted detailed interviews with two conductors and two participants of workplace choirs based in Berlin and London.

Röhlen’s interviewees described a sense of interconnectedness as a result of their participation in workplace choirs, an effect that brought them both relaxation and euphoria. They also experienced joy, confidence, and gratitude, Röhlen says, feeding into an overall experience of “self-transcendence”—a sense of going beyond their own ego and identifying a greater good.

Working songs

The popularity of choirs has a grass-roots evolution, starting with personal passions and small-scale efforts that, in some cases, have grown large.

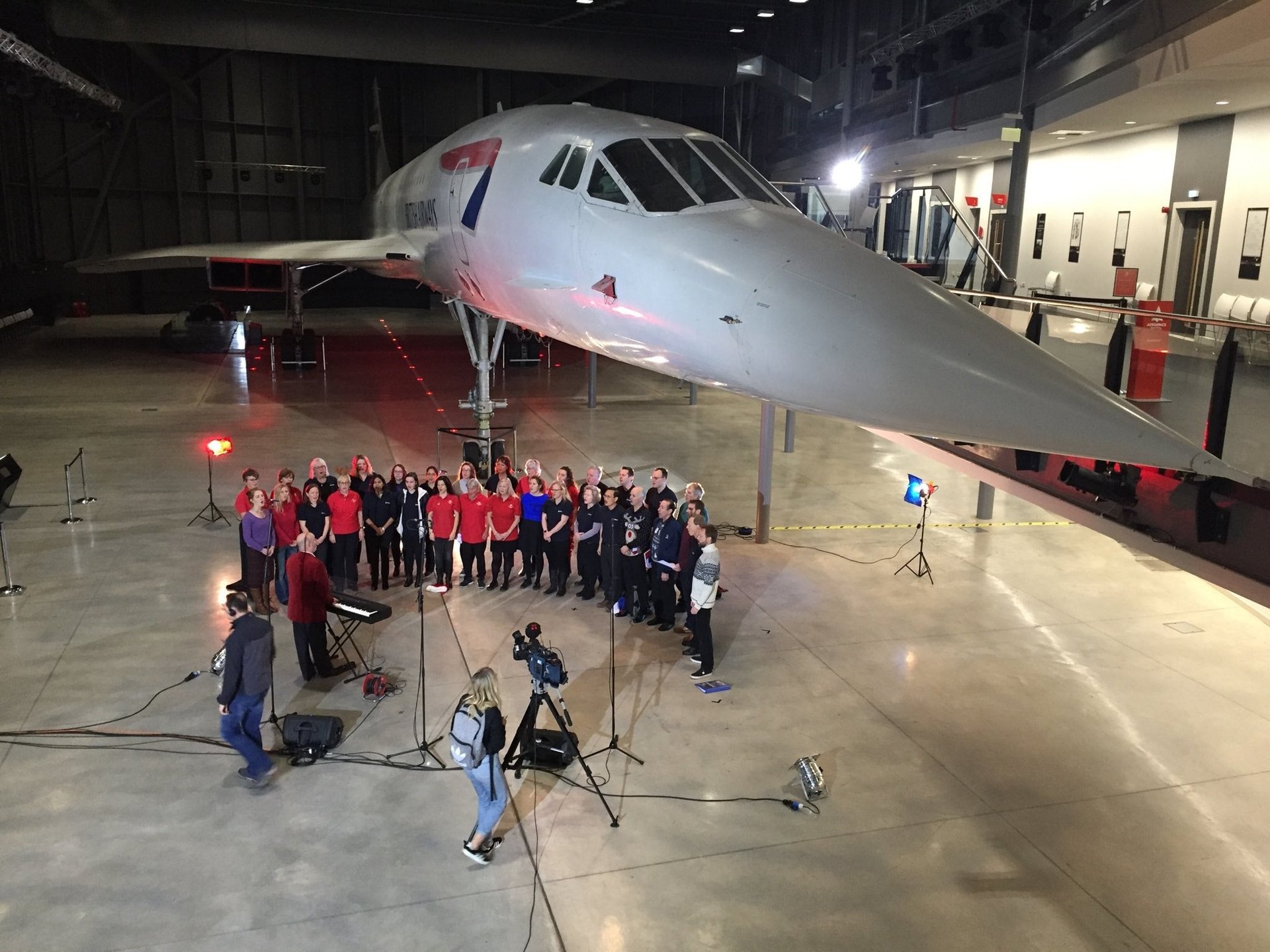

In 2012, a BBC TV show, The Choir, challenged workplaces across the country to form singing groups and compete against each other. David Ogden, a choirmaster with a background in church music, was brought on to rehearse some of the new groups. Years later he’s still in the post, running choirs that emerged from the show, including for aerospace company Airbus and Bristol’s Royal Mail. He also runs choirs for high-end travel company Sawdays and car-leasing company Arval.

Ogden says workplace choirs today continue a long history of workers using songs to commune during the day, from plantation slaves, to fishermen, to coal miners. Choirs historically “were designed to build community, and that’s what it does,” Ogden said. “You’ve got young and old people, people from different sectors” singing together. There’s the physical enjoyment—the “delight of singing a song you know, just whacking it out”—but there’s also the sense of collective effort that, in some jobs, is lacking.

Ogden also makes the point that, in some industries, the immediacy of song is a revelation. When Airbus started its choir, participants were amazed “that they could learn a song in a couple of minutes” when designing a plane takes 10 or 20 years, he said. With song, workers used to long timelines “get that sense of achievement and sense of satisfaction much more immediately.”

And, finally there’s recognition. The applause and public praise associated with performance can be totally alien: “People may never have done anything in their lives they’ve received a clap for…[especially] as an adult.” That recognition is powerful, Ogden says.

How the UK got its groove back

The proliferation of singing groups comes at a moment when employees and managers—particularly in the West—are becoming concerned with how healthy and happy our workplaces truly are.

This reflects the convergence of two forces. The first is a deep interrogation by workers into how we seek and derive meaning from our jobs, with the ultimate aim of avoiding burnout and combatting a potentially damaging compulsion to work that drains color and light from our wider lives.

The other is an increasing acknowledgement by employers that the health and happiness of a workforce is intimately bound up with workplace culture. Just this month, the former leaders of a large French telecom went on trial for the part the company’s culture may have played in the suicides or attempted suicides of over 30 current or past employees. At the other extreme, perhaps, are companies like New Zealand’s Perpetual Guardian, which trialed and then implemented a four-day workweek for its employees at full pay, in recognition of their desire for greater flexibility and control over their work-life balance.

The confluence of these two forces has spawned wellbeing initiatives, from gym memberships to time off for volunteering. Many of the UK’s choir projects are self-organized and take place outside work hours. But a number are a perk, subsidized by the company and on company time.

The switch from complex dealmaking to the black-and-white notation and the weighted keys of a piano provides a welcome break for Patrick Massey, an in-house lawyer for Macquarie Asset Management. “Some people go for a run at lunch time, or go to the gym,” Massey says. He slips into a piano room near his office for half-hours of practice. In his limited spare time, Massey conducts one of London’s most successful amateur orchestras, the Pico Players.

There’s a practical reason to play at work: Pianos are loud. Practice at home in the evening might disturb neighbors or housemates. It is, paradoxically, at work, in the middle of the city, that Massey knows he can be free.

Every week Massey also has a piano lesson organized via Music in Offices, which since 2007 has been offering work-based music tuition, running choirs, and organizing music and song events at workplaces across London. “My motivation is very much to bring music more into daily life, for everybody,” says Music in Offices founder Tessa Marchington, who also set up the Office Choir of the Year competition, in which choirs from across the country have competed for the last ten years. “It’s a form of communication that can transform [experience], not only at an individual level, but also at a level of community,” she said.

A productivity addiction

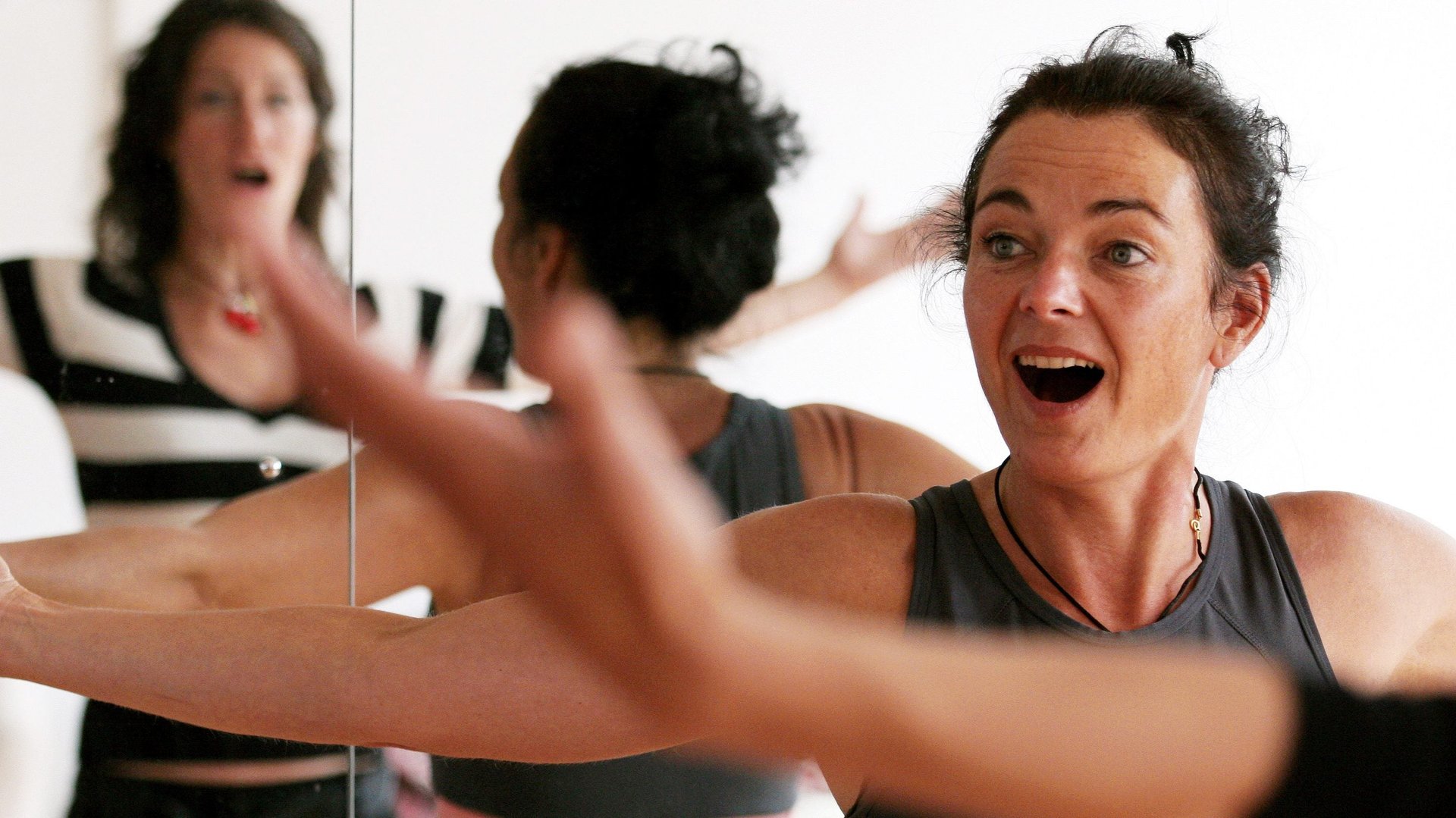

Eleanor Rose Rusbridge, founder of Sing At Work, a company that focuses on offering workplace choir-leading and song-based teambuilding days, argues that in a culture addicted to work, there has never been a better time for the releasing, leveling potential of song. Her company plans to put any profits back into companies’ localities by offering free choirs to community groups.

Rusbridge knows about addiction. For two years, she led a choir for the New Hanbury Project, a faith-based London charity that supports people struggling with addiction and homelessness. She argues that there are parallels between that experience and the “addiction to productivity” she sees in modern workplaces. Both, she suggests, can be combated with the communality of choral singing, which is distinct from many other social workplace activities—like post-work drinks—in that it doesn’t rely purely on chatting (or alcohol.) Choir is available equally to introverts and extroverts, she says.

“Companies are really beginning to understand why their staff’s wellbeing is important and why they have a responsibility to think about that,” Rusbridge says. “At its absolute basic level, singing is a very, very life-affirming thing.”